You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Do you know the work of Amelia Rosselli? She lived from 1930 until 1996, an Italian poet whose beautiful, blistering verses have only recently been introduced to English readers. Here’s a flavour:

What woke those tender fat hands

said the executioner as the hatchet fell

down upon their bodily stripped souls

fermenting in the dust. You are a stranger here

and have no place among us. We would have you off our list

of potent able men

were it not that you’ve never belonged to it. Smell

the cool sweet fragrance of the incense burnt, in honour

of some secret soul gone off to enjoy an hour’s agony

with our saintly Maker. Pray be away

sang the hatchet as it cut slittingly

purpled with blood. The earth is made nearly

round, and fuel is burnt every day of our lives.

There is much to consider in these lines. The corpulence of “tender” and “fat”, in contrast with the hard sounds of “bodily stripped souls”, “burnt” (twice) and “hatchet as it cut slittingly”, for example. Rosselli revels in physical detail: the “fermenting” bodies and “cool sweet fragrance”, as well as the “potent” men and the contradictory “enjoy[ment]” of “an hour’s agony”. Threaded through this verse is a clear sense of exclusion, of lines being drawn and crossed. We read it in the direct address – “You are a stranger here/ and have no place among us”, and “you’ve never belonged” – and in the imperative: “Pray be away.” The expulsion of the listener – the “you” – from”‘our list/ of potent able men” gives the act a gendered edge.

I know only three things about Amelia Rosselli. She was the daughter of Carlo Rosselli, famed activist of liberal socialism and founder of “Giustizia e Libertà” (Justice and Liberty), which sought to resist Italian fascism with militant action. She killed herself in 1996 by jumping out of the window of her apartment building in Rome. And she is one of Elena Ferrante’s favourite poets, according to a feature published by the New York Times last year.

You can see why. There is a substantial overlap in subject matter. Both paint vivid pictures, replete with sounds and smells. Both problematize language: Rosselli by slipping between Italian, French and English in her poetry, and Ferrante in her dual linguistic structures of academic Italian and violent “dialect”. And finally – perhaps most importantly – both demonstrate a fascination with the idea of the marginalized. The outsider. The absent.

The pseudonymous Ferrante embodies this idea. Her very existence is an absence, and her remarkable popularity attests to the notion, put forward by Wallace Stevens, that the unknown “has seductions more powerful and more profound than those of the known”. The fact that she insists on a state of anonymity intrigues people, prompting investigations (such as that of Professor Marco Santagata in Corriere della Sera last month) into her true identity.

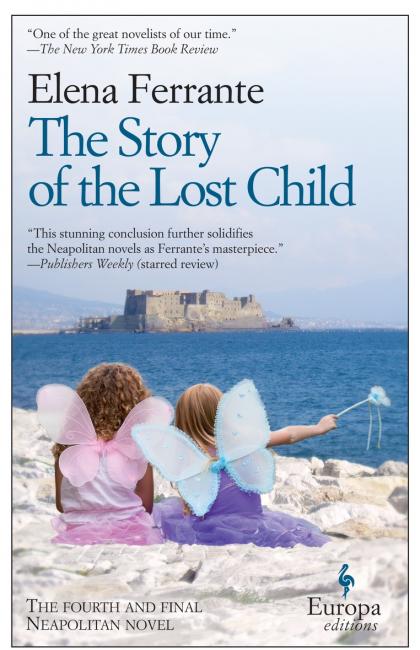

This sense of absence, of existing somewhere beyond the spotlight, permeates Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. These four books, the last of which – The Story of the Lost Child – has been shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, tell the story of best friends Elena and Lila. The novels take the pair’s experience as their focus, describing from the perspective of Elena their childhood in the suburbs of Naples, their education, their loves and losses, their respective careers. Beyond this central relationship is the panoramic backdrop of a changing Italy, as well as a multitude of characters, and the distinct worlds of academic thought and gang-ordained violence.

The significance of absence is clear from the get-go. My Brilliant Friend, the first book in the series, has on its cover a picture of a marriage scene in which the bride and groom face away from the reader. This theme is revived in the covers of all four books: it is always the backs that are turned to us, never the faces. It won’t be giving too much away, I hope, to say that the last book, The Story of the Lost Child, has at its heart a disappearance: the clue is in the title. But all four books function around a wider, more decisive absence: that of Lila herself, who, at sixty six years old, erases herself completely, cutting her image from family photographs, leaving without a trace. This is Elena Greco’s motivation for writing the narrative; she hopes to commit to paper the memory of Lila, writing “for months and months and months to give her a form whose boundaries won’t dissolve, and defeat her”. “One doesn’t tell the story of an erasure,” Lila tells Elena scornfully in The Story of the Lost Child. The very fact of these novels proves her wrong: each book expands further on this theme of erasure.

Absence, then, plays a narrative function for Ferrante. But, to return to Rosselli and the exclusion of the “stranger”, the “you” who has “never belonged”, it also plays an emotional role. A fear of unbelonging is essential to Elena Greco’s story. Her desire to fit in – intellectually, visually, linguistically – is powerfully conveyed. This concern for the experience of the outsider is clear throughout the novels: not only are they literally situated in the margins of the city of Naples, in the so-called “neighbourhood”, but they also concern themselves primarily with the lives of women. Despite growing up in Naples, despite being as conversant in the politics of the neighbourhood as the men, the women at the centre of this series are familiar with the shock Woolf describes in A Room Of One’s Own, “say in walking down Whitehall, when from being the natural inheritor of that civilisation, [a woman] becomes, on the contrary, outside of it, alien and critical”. Elleke Boehmer writes with characteristic eloquence on the significance of this leap from the male-dominated centre to the marginal female perspective: “The shift of women’s experience to centre stage displaces, indeed replaces, the national imaginary from the foreground,” she writes, explaining elsewhere that the narrative is therefore necessarily relocated to “literally peripheral spaces”.

These “literally peripheral spaces” are fundamental to the Neapolitan novels – not just geographically, but psychologically. Throughout her life, Lila is afraid of “dissolving boundaries”. We learn that “she had always had to struggle to believe that life had firm boundaries, for she had known since she was a child that it was not like that – it was absolutely not like that – and so she couldn’t trust in their resistance to being banged and bumped”. All the characters show an awareness of this dissolution of boundaries: of legal boundaries, of social ones. In Alfonso, an old friend of Elena, “the feminine and the masculine continually broke boundaries with effects that one day repelled me, the next moved me, and always alarmed me”, while Lila recognises that “all I had to do was find [Michele’s] boundary line and pull, oh, oh, oh, I broke it, I broke his cotton thread and tangled it with Alfonso’s, male material inside male material, the fabric that I weave by day is unravelled by night, the head finds a way”. Ferrante acknowledges the thematic importance of this transgression of boundaries in an interview with The Paris Review:

I have a small private gallery—stories, luckily, unpublished—of uncontrollable girls and women, repressed by their men, by their environment, bold and yet weary, always a step away from disappearing into their mental frantumaglia. They converge in the figure of Amalia, the mother in Troubling Love—who shares many features with Lila, if I think about it, including a lack of boundaries.

Can this “story of an erasure”, of absences, of marginal perspectives, hope to win the Man Booker International Prize? The prose is enough to convince me, described by Ferrante herself in The Paris Review as inclining to “an expansive sentence that has a cold surface and, visible underneath it, a magma of unbearable heat” (a far cry from Elena Greco’s self-reproach in Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay: “How could I have come up with such pallid sentences, such banal observations? And how sloppy, how many useless commas; I won’t write anymore”). Like Rosselli, Ferrante’s language – translated into English by Anne Goldstein – is many things: enthralling, scorching, urgent. Forcing its readers to hurry, breathless, to keep up with its pace. And like Rosselli, her interest in the excluded, in the marginalised and the boundary-transgressors, is the thing which sets her writing apart.

The Story of the Lost Child is published by Europa Editions.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.