You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

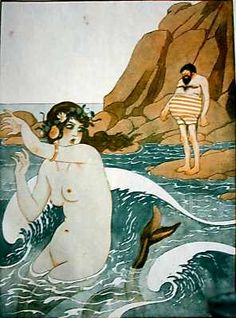

Selkie stories are the worst kind of stories. They’re always so formulaic: man finds dingy seal skin on the seashore, takes it home thinking to make a quick buck, returns to the shore and almost jumps out of his own skin finding a beautiful woman there, naked. Of course, he falls in love, he takes her home, they get married. Happy ending, right? Hah. In all these stories, the man will make some mistake, and the woman finds the skin. Immediately, she jumps back into the sea, already in seal form, and swims away while the man chases after her in vain. It’s far from a fairytale ending– at least, not for the man, or his children, who wake up the next morning finding they have no mother.

***

“Can you tell me about your mother?” The therapist leans forward, smile pasted on her face. We’ve been here for about an hour, and her patience is wearing thin. I lean backwards, studying her face impassively. In the distance, waves crash on jagged rocks, while a lone seagull circles overhead.

“Moira?” my father says evenly, and I am reminded that the therapist is doing me a favour, agreeing to see me on such short notice, that we are struggling to make ends meet and every minute I waste is money down the drain. So I grit my teeth and rattle off a long list of characteristics – brown hair, grey eyes, medium height, willow-tree slender, spoke with an accent no one could quite place, loved swimming, gave birth to me, took care of me, left me. When I finish both her and my father are staring. There’s something in my father’s eyes, an emotion I can’t quite place.

The therapist taps a pen on the table, disappointment evident in her eyes. “Maybe we should try again tomorrow,” she says, in a not-so-cheery voice.

As the therapist leaves our cottage, driving off in her black Jaguar, jarringly out of place in our rural fishing village, I look down at the floor, away from my father.

He clears his throat, and I think he’s going to reprimand me for the unsuccessful session, but instead he says, “Moira. It’s not weakness to tell someone how you feel, you know.”

I nod. He turns, and climbs up the stairs to his room. I watch him go in silence. How can I explain that when I think of her I feel only numbness?

It scares me a little, my lack of feeling. Googling ‘how to cope with loss’ merely produces the clichéd mantra of “Let it out, don’t hold it in” and provides ten-step lists on how to Move On With Your Life. Some bring assurance that the ‘tears will dry up’ in time, even if the sadness never goes away altogether. Other, only slightly more helpful articles say it’s okay if you don’t cry at once, some people cope with loss differently. All say it’s detrimental to bottle up your grief, and encourage me to ‘find things that distract you’. None tell you what to do if you haven’t shed a single tear in all the sixteen months since your ‘loss’.

On the other hand, most people who lose selkies have no problems letting their grief out, or so the tales imply.

One of the most famous tales is about the man who was so afraid to lose his selkie wife that he carried the skin around everywhere he went. Predictably, one day he forgot to take the pelt out from underneath his pillow, and while his wife was changing the sheets, she found it. When he found out, he ran all the way to the sea and bawled like a baby there, even though she was long gone. Then there’s the jealous axe-wielding maniac who hunted down and stabbed the selkie lover his wife made off with once she found her skin, or the husband who swore never to remarry and shut himself off in a cave by the sea.

In all these stories, grief is one-sided. The selkie never shows any hesitance, never stops to consider whether life on land was really that bad, or the consequences of her departure. You have to wonder: did all those selkies end up with terrible husbands, or did those years of marital life just not mean anything to them? Did they forget about their two-legged families the moment their flippers hit the water?

***

The next morning is a Saturday, so Dad doesn’t go to fish. We eat breakfast together, which is unusual for us; ever since Mom left, he goes out even before I wake up for school. Just before he leaves to disappear somewhere – probably to hang out with his buddies or something – he says, “She’s coming at two,” and for a moment my heart leaps. Then I realize he’s referring to the therapist.

She comes promptly on the hour, clad in a smart grey coat that’s warmer than anything the locals wear. I force myself to push the thought of another very different type of coat out of my mind. We sit in the same positions as yesterday, and she peppers me with questions: When did she leave? April 17, more than one year ago. Were you there when she left? Yes. How did she leave? This I am vague about, only mentioning that she whisked her coat on and disappeared out the doorway. Mostly the truth.

“Did you ever think about going after her?”

“No, never,” I lie.

Actually, I did. After she left I almost took my dad’s boat and sailed out into the ocean to find her. Rather stupid, I know, it’s not like one seal looks very different from another, but some part of me thought she might recognize me and feel bad about what she had done. I had envisioned our reunion perfectly: I would be drifting out in the ocean; a seal head would pop out from the water; we would lock eyes, mutual understanding between us; she would change back into a human there and then and clamber onto the boat; we would sail home and live happily ever after.

In the end I didn’t do it. Partly because it was almost impossible to get the boat – Dad uses it in the day and locks it up in the shed at night – but also because I was afraid. Not that I wouldn’t be able to find her or that Dad would give me a huge dressing down, but that she would see me… yet refuse to return.

***

If I could talk to my mother, face-to-face, this is what I would ask:

1. If she has a new family now.

2. Or if she always had a seal family and all the time she was with us, she was pining

after them.

3. If she ever misses life on land.

4. If she ever considers coming back. Maybe not to stay, but just to visit, say hi to her

old friends, tell me what it’s like living in the ocean.

If I could talk to my mother, face-to-face, this is what I would tell her:

1. That the month after she left, I became an expert on seals, and the essay I wrote on the social structure of grey seals received an A+.

2. That in the exams held before the holidays started, I was first in class for biology and second in literature.

3. That I received an offer from a school in London but I turned it down, because I didn’t want to leave.

4. That I haven’t forgotten anything about her, like the way her hair gleams copper when the sun shines on it, or the way her eyes turn darker when she’s sad.

I wouldn’t tell her that I see her all the time; in the flick of a tail on the shoreline, in nature channels on television, in shop windows, hanging on silver hooks. I wouldn’t tell her about the nightmares I had, of her caught bleeding in nets, or torn to shreds in the jaws of a shark. Nor would I mention the time I saw tourists snapping photos of a litter of seal pups gamboling in the sea, and purposely kicked up stones to scare them away, or that I know Dad goes to the shore where he met her every weekend and just stares into the distance. I wouldn’t tell her that I stopped going to the pool where we used to swim, because I couldn’t shake off the memory of her racing me side by side, her sleek frame slicing through the water like a knife.

I wouldn’t tell her, most of all, about the day I went to the zoo for a biology study, and when we passed by the seal enclosure they recognized me, pressing their whiskers to the glass and crying out in a language I could understand. I cut my hair that day, hacked it off clumsily with a scissors. I wouldn’t tell her that for months afterwards, I raced to the door every time someone came knocking and picked up the telephone on the first ring, because each time I hoped it might be her. I wouldn’t tell her that goodbyes are painful, but at least they’re better than nothing.

***

I am sprawled on the couch, thinking about a selkie story while half-heartedly watching television. It’s one of the few tales that involve the selkie’s children; it’s also the only tale that infuriates me. In this story, while the selkie’s husband is out at sea fishing, her child notices her peering out of the window at the ocean, the very picture of melancholy. When he asks what’s making her so sad, she replies that she’s lost something very precious to her. Her son then crawls under the bed and produces an old seal skin. “I saw Father taking it out,” he chirps. The precocious kid then relates how he’s somehow always guessed his mother was a selkie. “Go, mother, be free,” he announces, and the rest of his siblings, who have conveniently been hiding in the cupboard all this while, echo after him.

This drives me so mad. Even ignoring the fact that no five-year old is that perceptive, what kind of child encourages his mother to leave like that with the knowledge that she will never come back? What kind of child is so selfless? And what about her? Did she stop to think about what would happen to them, left with only a grieving father? Did she think about anyone else at all, before she made her move?

These are the thoughts running through my mind when I slam my hand on the sofa and accidentally press the remote control, changing the channel to National Geographic. It’s a documentary on the wildlife in New Zealand. The screen fills with images of shoals of fish, dolphins leaping, and then a beach teeming with seals. “Fur seals are abundant on the beaches of Kaikoura, especially at this time of the year, the breeding season.” Cut to a mother seal nuzzling her pups, who wriggle happily under her affection. “Female seals are highly protective of their young, and will challenge anyone who dares to venture too close…”

I turn the television off. It’s not cold, but I’m trembling. I shrug on a jacket and head out of the door, walking without looking where I’m headed, focusing only on the rhythmic pattern of my footsteps. Without realizing it, I have reached the edge of town. Just a few steps ahead of me is the shoreline. I know this shore; it’s where my father sets off to fish every morning. It’s also where he met my mother.

The selkie story I try not to think about the most is one involving a girl. She finds the skin in the attic and brings it to her mother, thinking it would make a nice winter coat. Needless to say, her mother takes the coat, kisses her on the forehead, and vanishes, without a single word.

You can imagine who that girl was.

I sit down on the formation of rocks and try and imagine them meeting. Was he captivated by those startling grey eyes, that lustrous mane of hair? Was she afraid, or was some part of her also drawn to him, like a moth to a flame? I’ll never know.

Beyond me, the ocean ripples, stretching out into infinity.

About Sarah Ang

2016 Litro & IGGY International Young Writer Prize, 16-year old Sarah resides in the city-state of Singapore. Her works have been or will forthcoming in The Claremont Review, Cultured Vultures and Page & Spine.

Hi. This is a nice story. I remember being a Selkie in a past life. I still long to go back to the sea and think of it as my home…

I believe I am half selkie or half mermaid. I long to know which and find others like me.

Wonderful story! This is such a beautiful idea, and beautifully written. I loved it.

Isn’t this a rip-off of Sofia Samatar’s rather wonderful ‘Selkie Stories Are for Losers”, published 2013 ?

https://strangehorizons.com/fiction/selkie-stories-are-for-losers/

Oh SHIT!!!! That sucks!

This story is bomb as hell but… That story is obviously a little more fleshed out and also… Published three years before this one.

Yikes.

Wow, talk about plagiarism! How did this get published here? Kinda disgraceful.

But also: what a clunky piece of writing. It’s clear the writer knows nothing about the location, what life might be like in a fishing village, and didn’t bother to put in any decent research into rectifying this. There’s no spark to anything. The prose is laboured and cluttered with cliches. The characters are cardboard cutouts. Why would the father remain in the room during a therapy session? Why does the narrator tell us every thought and feeling they’re having, yet somehow claim not to know how to tell anyone else?! How many fishermen keep their boat in a “shed”?!? It’s beyond laughable.

So, yeah: stolen story, and not even well executed.

This is poorly written plagiarism and needs to be removed from this site.

I’m pretty sure the selkie marrying the human was always against their will. Can you really blame her for running away first chance she got? If you love someone, you shouldn’t have to carry a magical item to keep them in captivity.