You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Learning to ride a bike as an adult is like that scene in Bambi where she can’t walk on the ice and keeps face-planting, except with less adorable eyelashes. Remember how Thumper charges ahead, spinning about and telling Bambi how easy it is? There’s plenty of that too, except instead of a cartoon rabbit, its lads on bikes doing wheelies or five-year-olds speeding up a hill while you struggle to even push off.

Learning to ride a bike as an adult is like that scene in Bambi where she can’t walk on the ice and keeps face-planting, except with less adorable eyelashes. Remember how Thumper charges ahead, spinning about and telling Bambi how easy it is? There’s plenty of that too, except instead of a cartoon rabbit, its lads on bikes doing wheelies or five-year-olds speeding up a hill while you struggle to even push off.

Learning in London is particularly bad. The city turns into an obstacle course at best, a death wish at worst. Going on the roads is completely out of the question, with over four hundred serious injuries per year and women much more likely than men to be crushed by HGVs, which isn’t quite how I’d imagined going. Parks aren’t much better. In Hyde Park, the only bit you can really ride along is colonised by MAMILs who still wish they were Lance Armstrong even if he did turn out to be a bit of a dick. Even in parks which have more cycle paths and less yellow jersey wannabes, it’s not great. As an adult on a bike, people think you’re in control of your steed. They randomly stop pushchairs in front of you, joggers refuse to deviate from your path and toddlers career about with an unseeing naivety so adorable when you’re not worried about maiming them. And the seemingly unstoppable fashion for small dogs makes every foray into pet roulette; several park benches have had the pleasure of my front wheel smashing into them as I avoid yet another wheezing pug. Their owners look at me scandalised, how could I have nearly harmed poor little Pugsley? What I really need is a Learner Sign slung around my neck. It would be more effective than the Scream-like contortions of my face as I try to communicate imminent GBH to Pugsly’s owner.

I have, as it happens, worn an L-plate around my neck before. It was on my hen do. I kept it on all day at the Beyoncé Dance Party Experience (bring your bridal sass!), through the pop-up supper club and when we played pin the tail on the butler in the buff. It survived the East London nightclub where men mistook its red and white lines for target practice. The cultural symbolism of it didn’t make a whole lot of sense then. What was the link between motoring and marriage? What sort of vehicle was I pretending to be – a petite mini? A sexy SUV? Or was it some prurient hint at my upcoming induction to the marriage bed, the red on white harking back to the old tradition of hanging bedsheets smattered with bridal blood out of the marital window? Whatever the lineage of this grand hen do tradition it makes a lot more sense now because two years down the line, I’m getting divorced. It turns out it was a learner marriage after all.

You don’t hear much about young divorce. Generally, all the marriage breakdown chat is about how fifty is the new forty, how you can revivify yourself as a mid-life ex-wife, how to do online dating as a silver surfer … but divorcing at thirty? The least sympathetic people think you probably deserve it, just a little bit, and the most concerned ones suggest it can’t really be that bad. Thank god you didn’t have children, they say, no custody battles. Sure, thank god. Sounds traumatic. Thank god I don’t know if I’ll ever have the family I’d imagined, the kids I wanted to raise as courageous, creative little beings. Thank god I have the banal intimacies of Tinder to contend with instead of the loving disgust of toddler snot. Thank god every man I meet is going to be a little afraid when I confess that someone has already put a ring on it. Thank god all I have left of my dreams are a divorce form and a £550 court fee. These things, they make you very old, whatever your age.

That’s why I’m learning to ride a bike. The bicycle is youth. It is a possibility. It is the reclamation of my own body to propel me into a future which I can’t see but know is out there, somewhere. I’ve swapped the metal round my finger for metal under my legs and it turns out the latter has a whole lot more potential.

I am not the first woman to discover this.

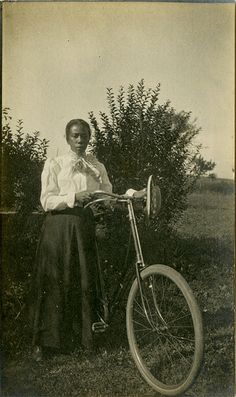

Never having thought much about bicycles before, it turns out I am part of a long line of women discovering the empowering effects of the pedals. Frances Willard is my favourite, not least because she looks so priggish. Hair parted like a knife, mouth so firmly pressed it might be starched and pince-nez giving her the air of a judgemental owl. But looks deceive and Willard did something pretty cool in her time: in 1892, when she was fifty-three, she learned to ride a bicycle. She was part of the movement of the “New Woman”, which arose alongside the increasing availability of “safety bicycles” (our normal bicycles, instead of the unwieldy penny-farthing style) in the 1890s. This newly democratised method of transport gave women the ability to travel around unchaperoned using nothing but the power of their own bodies. These lady bicyclists were, according to nineteenth-century women’s rights activist Susan B Anthony, “the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood”. They cast off their heavy underskirts and corsets in favour of the new “rational” style of dress, which saw bloomers, and even trousers, making an appearance. The sight of women sitting astride a metal horse with buttocks and thighs visible led to much conservative criticism and moral panic. The second sex was unchaining herself from household and husband. Some took this newfound emancipation global, like incredible Annie Londonderry who cycled round the globe in 1894 after two men made a bet that no woman could achieve such a thing. Others empowered women on a more local scale, like Maria Ward, who published a manual for women to learn bicycle maintenance. Such was the general disbelief that women could manage “masculine” mechanical skills that Maria had to state upfront “I hold that any woman who is able to use a needle or scissors can use other tools equally well”. All these women struck out against social expectations. My divorce is personal and tiny in comparison but still, when I’m on the saddle I feel something kindred with our bicycling foremothers. There is a strength to be tapped from their “unbecoming” decision to go against convention.

*

There are times in life when you’re not supposed to do certain things. You’re not supposed to divorce at thirty. In fact, according to the Office for National Statistics, I shouldn’t even be married for another four years. And you’re not supposed to learn to ride a bike at fifty-three, but Frances Willard did. In the memoir, she wrote about it, A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, she said she “wanted to help women to a wider world”. This is precisely what the bicycle provides. Divorce reduces your future to rubble. It has erased itself. What are you supposed to build now? How do you colour in an empty space? Learning to ride helps to navigate this blankness, reminding you that you still have your inner child, that you can learn to colour it all in again like turning the page in a colouring book. It teaches you about yourself, giving you what Willard describes as a “whole philosophy of life”. It is teaching me to slow down when a tricky corner is up ahead, to take time and breathe as I sail around it. It is helping me to see that the best way to navigate narrow openings is to focus on the space itself, not the obstacles either side. I’ve learned that the bike responds best to confident encouragement of the handlebars, not jerking commands of fear. I’m figuring out how not to get spooked by pugs or cars or whatever else comes my way – they will come and they will go. And I’ve learned that even when you’re feeling very, very old, right down to your bone marrow, you can still be young at the same time. You can learn to ride a bike. It’s like Bob Dylan says: “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

I’ve been learning on a friend’s bicycle but I think it is time to get my own. Frances Willard called hers Gladys because of the “exhilarating motion of the machine, and the gladdening effects of its acquaintance and use on my health”. I am going to call mine The Gay Divorcee and I am going to take her somewhere brilliant and new, whether it’s down the backstreets of Islington to get a pint of milk or round the globe like Annie Londonderry a hundred and twenty years ago.

About Emily Kenway

Emily Kenway writes essays, creative non-fiction and fiction outside her day job working on human trafficking.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)