You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingRead part one of “Lulim Lalai: The Power of Life In Country” here.

The Wanjinas created everything

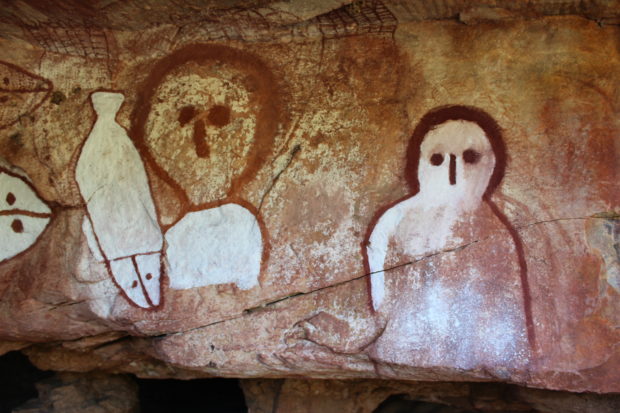

Isobel’s country, along with other parts of the Kimberley, is famous for its sacred Wanjinas – creation gods – sometimes painted with cumulus clouds around their heads.

Discussing these highly sacred images reflexively causes anxiety, as Isobel was raised to respect these gods so greatly that the subject was generally avoided.

“My mother tried never to say the word Wanjina, and if she ever had to say it, she whispered it,” says Isobel. “They are painted without mouths because there are things never spoken, things you should never know. Not until the right time. Otherwise, you will lose your mind. It will make you go completely insane.

“Sometimes, even when you visit the sites, it’s the wrong time, the stories will get stuck. The knowledge is frozen. It’s okay. You just wait, and the right time will come.”

History and the intense interest in Wanjinas by foreigners has forced Isobel’s people to speak about them, though they would not have in the past, not to anyone outside their tribal kinship and belief system.

Isobel shares a story of her old people – the one story that never changes: The Wanjinas created everything in the Lalai, the Dreamtime, including all the laws of nature and society.

This determined which clans belong in which territories, the totem animals, the relationships between all things, including rules on marriages – highly elegant regulations that have successfully protected against inbreeding among small populations for tens of thousands of years.

Isobel and her son Neil explain that the Wanjinas had to return to earth after the Dreamtime, the Lalai, because tribal people were ignoring the laws.

They reset the laws with humans, then they left their images in the caves, where they can be seen in the paintings, touched up over thousands of years. Other, select clan members are asked to touch up the paintings when the time comes; it’s always done by men. Isobel’s Arraluli clan doesn’t refresh its own paintings.

Before approaching her sacred sites, Isobel calls out to the spirits in Worrora to warn them.

“I’m telling them a foreigner is coming through,” she says. “Don’t take it the wrong way though, I would say the same thing about an Aboriginal person who’s not part of my clan.”

After we leave each site, Isobel makes sure that smoking eucalypt branches are waved around us, from head to toe, to keep the spirits happy, keep the bad spirits away.

Isobel belongs to one of a number of clan groups who make up the Worrora tribe, each with their own estate. The Worrora are also connected, via shared Wanjina law, to the Wanambul tribe to the north and the Ngarinyin tribe inland and to the south. The bonds between all three tribes are close, and they comfortably speak each other’s languages.

Her clan, which descends through her grandfather, who had only daughters, and with all males of the descendent line dead, has been determined by patrilineal descent. Isobel has six children by a tribal Ngarinyin man. Now dead, his name is not spoken.

“But I also have a promise husband and he’s still alive. We all get one,” Isobel explains.

“We don’t have to marry each other if we don’t want to, but we do have to look after each other. My promise husband Neville’s a Worrora man. He’s in his fifties and we still look out for each other. I can go up to Neville any time and tell him what to do. He’ll do it.”

We recognise each other by seeing the forehead first

The Wanjina’s law means everyone is clear about who they have responsibility for. The three tribes recognise each other immediately because they “see the forehead first”. In the course of conversation, and even in meaningful silences, it tilts forward frequently.

“It’s how we say hello.” Isobel smiles. “Look. There’s no word for it, we just do this.” And she bows slightly, eyes lowered and forehead upright.

“I will always recognise one of my people. I’ll know how I am related to them, by birth or by skin, which is clan, by marriage, and what my obligation to them is. I keep track of hundreds of people this way.

“And I also respect other people’s land. We all know where we belong. If I’m going through someone else’s territory, I tell them don’t worry, I’ve got my land, I’m just passing, and then they can relax.

“Our clans are connected directly to land. Because I’m Arraluli, my estate is the Lulim – it’s always been this way.

“We’re spirit people. Everyone in this tribe who believes in their culture believes that their spirit comes from this country. A father will know the spirit of his child. Water is very sacred. The spirits of babies are usually associated with fresh water. It could come in a dream, or maybe in an animal they hunt, and usually the child will have that marking. If it was a kangaroo and they speared it, then the child will be born with that mark, so we know that’s the spirit.”

The relationship between knowledge, obligation and social order is more sophisticated than anything I’ve experienced in Japan, or the Middle East, let alone Italy or France. In country, conduct is highly regulated. Men and women don’t spend a lot of time together; we each have different tasks to be getting on with. The way we speak with one another, whether or not, or how, we might touch, is all subject to a correct approach.

We’re saltwater people

This has been challenged in the past. Isobel’s mother Amy moved with the rest of the tribe to Derby when they were relocated from Wotjalum in Walcott Inlet. Here, she had to speak those local languages, outside the three languages of her Wanjina community, as well as English.

In this new community, the ways of the Worrora were kept strong along with the rest of the Wanjina tribes, but there was also a fundamental shift. Isobel’s mum and her tribe were adjusting to government decisions ruling their destiny, taking them away from their home and culture. But they had also been imposed on other Aboriginal people, they were living in another tribe’s country.

“We grew up having to know about six languages all together,” Isobel explains. “I was protected there, by my mum, my aunts and uncles. They taught me the right ways. They made sure that I knew my tribal ways.

“But you know around Derby there, they’re freshwater people. They’re different to us. We’re saltwater people. Every time I leave Lulim, I take as much sand as I can with me and I put it all over my mother’s grave in Derby, so everyone can see that she was a saltwater woman.”

Isobel heaps praise on some missionaries, in particular Rev Bob Love whose relationship with the Worrora began in 1914, and who, with his wife, ran a missionary in the region, at Kunmunya, between 1927 and 1940. Love wrote touchingly about Isobel’s mother Amy as a baby. Isobel has grown up hearing happy recollections of time spent with them, the first whites to really influence her people, as they worked out an appropriate cultural way forward.

Isobel remembers fondly her own time in Derby’s Old Mowanjum mission in the 1960s and ’70s, despite the very basic conditions and difficulties faced in one big community with Rambarr, the code of conduct preventing women from associating with sons-in-law or their families.

She practises Rambarr even in Perth among her own children’s in-laws. “They are Noongars, Indigenous Perth people, with their own ways, so they don’t understand. I ask them to please respect that this is my way, the Worrora way.

“If you think about it though, it makes sense. You don’t want a husband telling you their mum does things this way or that way. Otherwise, she’ll tell him to go back to his mum.”

When she’s in Perth, Isobel has to work hard at living two lives, operating in another world. “We change when we leave here,” she says. “We have to put on another image, but in a good way. We’re living in two worlds in our minds and in our belly and it’s good for us, if we can hold it here in our stomach and move around with it.”

As an elder even when she’s not in country, Isobel is busy with obligations to listen, to feed and support friends and family. Sometimes the house is so full there’s barely standing room.

“It can be tiring but that’s how that is,” she says. “In the past, I’ve given all the food in my house to family who needed it. Then my kids came home and said, what are we going to eat? I had to go over to friends and ask for food to feed my children. That’s just how it works.

“And I’ve got strong ideas, I don’t mind telling everybody. They have to stay fit and eat well. No alcohol. Get an education and work hard at school. And they don’t need things. The children don’t need lots of plastic toys or iPhones or anything. They need good experiences, good knowledge, not things.”

Native title

There’s a lot more space for everyone in country. Isobel’s Lulim estate is inside a 16,040-square-kilometre stretch of land belonging to the Worrora people through Native Title. For many reasons, including its remote location, its rugged and, to modern eyes, inhospitable nature, the land was never leased for pasture to European settlers; it’s never been cultivated.

Isobel’s Worrora tribe won Native Title without opposition in 2011. But this came after a protracted legal fight by others. The neighbouring Ngarinyin tribe, which shares the Worrora belief system, connection to land and many familial relationships, fought bitterly over four decades for its Native Title. Important old people, custodians of law and culture, died in the course of the battle.

Native Title is often administered in a non-Aboriginal way. Isobel, supported by key elders, worked with Native Title commissioners to help her own tribe understand that it gave Aborigines the right to organise their title according to the old ways of wurnan – by recognising the clan estates.

“Some people tried to tell our people you could just vote like a majority to go into someone’s land and do things,” she says.

“Our old system never did that. It was set up to protect everyone’s areas – even when smaller families lived there. That’s why some people say it’s the first proper system for humans sharing, to stop fighting and killing over things.”

The government and her tribe now acknowledge Isobel’s rights under the policy of “right people right country”, so she is able to do what she has dreamed of, to make her elders’ dream a reality and re-establish her tribal presence in country.

“I won’t say that my countrymen were wrong because they were told by others, who put them up front, that they were doing the right thing,” she says.

“They did some good things as well as things I disagreed with, and we spent a lot of time sorting that out. Now I am moving forward with my own family and with the support of my tribal families, to make sure our presence is back in country the right way.

“Our law and culture tells us if it’s the wrong way, we will be hurt, the children of our tribe will be hurt, that’s the way it is, and we saw that in Derby, where our small community among many problems, had the highest suicide rate in the world among young people.”

Isobel and her children now spend the Dry season on Lulim each year where they are slowly putting together their long held dream of a family cultural and wilderness register –bringing together all the values of this rare place for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. “The two-way thinking my elders talked about,” Isobel explains. “Foreign way and tribal way together.”

But while Isobel is connected, through her soul, through her upbringing, to this place, it is very remote. Medical attention is hours away by helicopter, if you can raise the alarm in the first place. She wants to live here all year round, but knows it will take more infrastructure before that’s possible. Isobel is under no illusion that living here for her people is not as easy as returning to live like the old people did.

“They knew everything from 50,000 years of living here and they had all the clans and families to support that,” she says.

“That was all broken down over a hundred years, so we are returning in that way our elders told us, this two-way one, where we live in this modern time but carry with us our law and our culture, that’s the way they told us we would survive in this time.”

Despite this, Isobel cheekily confides that every time she comes to country she doesn’t want to leave, protesting that she wants to stay on for the dangerous Wet season, even when she’s been unwell in the past.

“I say, just let me stay here and die on my land,” she says, laughing now. “I never want to leave.” But the remote location turns this into a risk others aren’t willing for Isobel to take.

Living well

It’s a simple fact that Isobel’s first job, in supporting her elders’ wishes, is to stay alive – stay healthy and stay alive. It’s a responsibility that comes naturally given her upbringing. Isobel’s clan doesn’t drink, limits sugary foods and drinks (sugary soft drinks are almost as dangerous as alcohol in her view) and exercises all day as they go about life on Lulim.

Her second job is to raise her children well, so they are able to assume the mantle when their time comes. Of Isobel’s six children, three live on Lulim throughout the Dry season and will probably be ready to stay there during the Wet in the near future.

“My other children are welcome,” she explains, “But they have very young children of their own, and I won’t let them bring disposable nappies. Everything artificial we bring to the land, any rubbish at all, we have to take back off at the end of the season.

“And also, the children need to be old enough to really listen. It’s dangerous here and we have to live carefully, respectfully.”

For Isobel, her mother and grandmother, the ways were learned, slowly, day by day. Even adapting to the food is a gradual process and part of growing up.

“There are only certain parts of the kangaroo or turtle that children should eat, for example,” she says.

“We leave the right part out in a shell for the children to take. If you eat the wrong part of the turtle it will make you sick, because your stomach hasn’t developed enough to handle it. We can always tell if children have gone behind our back and eaten the wrong part. They will be lying down holding their stomachs. It doesn’t matter, it won’t kill them; it teaches them a lesson.”

To live such a remote existence responsibly means eating well every day, keeping an eye out always for snakes on land, sharks and crocodiles in the water.

Isobel takes on personal responsibility for the health and safety of all life on Lulim. She considers and discusses pretty much the smallest decision carefully before determining what we will do and how we’ll do it. Is it time to collect wood, light a fire, visit a water hole or a cave, go fishing, cook, clean, swim? Shall we stay in the shade during the heat of the day and talk some more about wungud, the life force? There is a right moment and a right way for all activity.

Read the third and final part of “Lulim Lalai: The Power of Life In Country” here.

Litro’s mission is to find the best and most exciting new voices in fiction and non-fiction from across the globe and give them a platform for their work. Litro wants to continue to showcase the best emerging artists. You can help us by supporting our Crowdfunder Today!

About Lise Colyer

Lise Colyer is a former news reporter who tells stories professionally now in her role as a PR director. She also writes fiction, mainly novels and poetry, and still keeps her journalistic hand in with news stories and non-fiction essays here and there.