You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

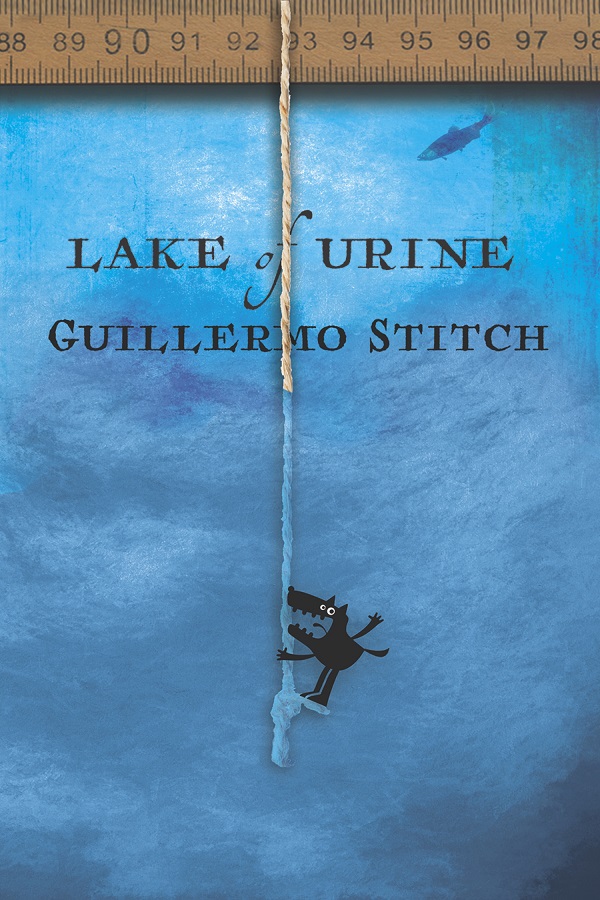

Guillermo Stitch is the author of the award-winning novella, Literature™, and the novel, Lake of Urine: A Love Story (Sagging Meniscus, 2020). His work has appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Entropy and Maudlin House. He lives in Spain.

*

Interviewed by Erik Martiny.

Your novel Lake of Urine has a rather provocative title. Did you consider other titles? Were you not worried that a title like that would put off some of the more high-brow reviewing newspapers, not to mention publishers and readers?

I can’t remember the precise moment of settling upon the title, but it was early on and it was immediately obvious to me that it was the only possible title. Authentically, anyway – the truth is I did subsequently consider alternatives, especially as the book accrued a complement of rejections. Some of them were OK, I think, but I won’t give them an airing here – in comparison with Lake of Urine, which my stellar publisher has never even queried by the way, they tended rather toward the twee.

If the title puts a reader off, then that wasn’t my reader, so the problem resolves itself, but I know what you mean about critics and publications. The book has yet to find its place in the world, so I’ll have to wait and see. I think the implication of your question is that some might dismiss the book as daft or puerile or both without having read it or, having reached whatever lazy conclusion based on the title, read the book inattentively. You may be right. Risks, you know? Risks and rewards.

Can you tell us the inspiration behind your beautifully mysterious pseudonym?

The point of using a pseudonym for me is that it allows me to maintain a certain degree of anonymity or, if that proves impossible in the age of social media, at least a degree of distance. With that in mind I must remain circumspect here, but I’ll say two things.

Firstly, part of the reason it’s difficult to answer this question is that I am still making the answer up.

Secondly, do you remember how Alfred Hitchcock would always give himself a fleeting, blink-and-you’ve-missed-it cameo in his movies? As a child, I thought that was cool and would watch intently, pretty much oblivious to plot. It wasn’t big and it wasn’t clever – just cool. Well, there’s an element of that.

Your pseudonym is as playful as the names given to your characters. Was Dickens your main influence when choosing these?

Yes. Dickens could be delightfully on-the-nose with his names and I suppose in naming my characters I felt licensed by that. Nobody else casts such a long shadow over the book, especially the third and longest part.

Swift also makes cameo appearances in your novel, most notably in the Brobdingnag Semiconductors. How far-reaching was his influence?

Specifically? Not very. It’s obviously just about impossible to imagine a world (or an imagination [or a literature of the fantastic]) without Gulliver in it. But that’s as far as it goes, I think. Maybe that sense of a cleansed, “blue sky” allegorical space? Maybe it’s Swift that I have to thank for that.

Do you see yourself as a specifically Irish writer or are your sympathies more cosmopolitan?

I see myself as a person who has spent what probably amounts to way too much time in the spare room, making things up. Two of your questions this time round begin with the words “Do you see yourself as…” and they stump me, I have to say. I think I would rather not see myself, preferring the outward gaze. I am very fortunate in that a book of mine will see the light of day. And after that perhaps another, and then maybe more. If the work gets any attention at all, then there will be that process, won’t there? Other people will decide, maybe reach some sort of consensus, on what it is that I’ve produced and what its value is, if it has any. That’s as it should be.

I’m a writer and I’m Irish, so there’s some compelling evidence. I’ve been conscious of Irish writers all my life but then also of Europeans, Americans, Africans, Russians, South Americans … was it Iggy Pop who said “It’s all disco”?

Do you therefore have no interest in autobiographical writing?

I suppose I subscribe to the view, today anyway, that autobiographical writing is inescapable – that in a sense it is the only kind of writing. I am not absent from my work; I’m all over it like a cheap suit, in fact, but endlessly reiterated. There might be a bit of me in this character or that, a bit of my story in this scene or that – but it’s an inevitability, not a deliberate act.

I think when you leave something of yourself in your work inadvertently, it will be all the more revealing for the reader who is looking for that kind of thing.

But the challenge for good fiction – am I wrong about this? – is that the reader should find themselves in there, not me. Were I to consciously seek to present myself, assert myself, via my work, I would feel like an intruder in an intimate encounter between reader and text, as if I were hiding in the wardrobe, horribly aware that my socks were still on the floor beside the bed.

Some of your characters’ names (like Amerideath and Vacuity) suggest allegorical heightening. Did you intend the novel primarily as a critique of American culture?

Amerideth is a real surname, you know – I just dropped the “a” in.

No, I don’t think I would want the book to be considered a critique. Not primarily, anyway – I obviously take swipes and there are clear satirical elements but I think a book, a story, should be too rich and animated a thing to be primarily anything.

Lake of Urine is a particularly playful novel. Was the spirit of American postmodernism a driving force behind your stylistic and formal approach to storytelling? I’m thinking of Donald Barthelme in particular. Do you see yourself as a belated postmodernist or a neo-postmodernist?

I hope I’m not a belated anything. I’ve always considered myself to be quite a punctual person. I’m aware of the traditions, the delineations – but I am not driven by them. I love Barthelme but not because he’s postmodern. I could fill a page with the names of writers who have produced work I love, and all of the named would by now have been placed within a tradition by critical theory, but I don’t love any of those books because of those traditions.

What drives me is much more personal and much more rooted in early life, I think. It was when I put theoretical concerns aside that writing became possible, for me.

There’s also a postmodernist fairy tale atmosphere to your novel. What are the fairy tales that you had in mind when you were writing?

Noranbole’s arc is that of a subverted Cinderella. There’s also a kind of Fairy Godmother, and a sort of Wicked Witch. I don’t want to get too close here to explaining specifics, but Pinocchio is in there. The Goose that Laid the Golden egg. The book has a fragmentary relationship to a number of old tales. Broken bits of them show up as shards in its mosaic.

How close do you feel to the concerns of magic realism?

See my above observations regarding critical theory and my relationship with it. If anything, I am marginally more comfortable with the term fabulism – which invokes both Aesop and Calvino – to describe my work.

Don’t get me wrong – the reader who turns to my fiction looking for something akin to the wisdom of Aesop needs a good talking to.

But I am drawn to this idea that what we are after a story is different, and better, from what we were before. That when our fictions hit the truest notes, we are transformed.

I have always liked the term magic realism though. Magic is … well, it’s magic, isn’t it? And reality … is OK too, after the second coffee. And the combination of the two words works well to circumvent this supposed distinction between realism – the realist project – and other strategies.

Are you aware of American Weird fiction? Do you feel close to it or part of any movement similar to it?

In matters of membership or affiliation, I am a devotee of Groucho Marx.

Some of your characters speak in several different languages in the course of a single conversation with the same person. Bernard for instance even speaks in binary computer code, but Noranbole understands him perfectly. What was your aim in doing that? Is Bernard supposed to be some kind of robot or enhanced human being?

Bernard is … misunderstood. But not by Noranbole.

Can you tell us about your process?

When I am in the throes of a thing, I get up early, take care of any domestic tasks which might otherwise be hanging over me, break a quick sweat running, then sit down and write. After between four and six hours I dry up, or shut down or however you want to put it, but go back to things late at night. In fact a lot of the ideas that move a thing on come late at night.

I do not allocate distinct blocks of time to writing, editing, research and other elements. They all go in the mix together.

I am slow. Things need to brew.

Are you working on something new at the moment or giving it a rest after the writing of Lake of Urine?

I’ve been working on something ever since finishing Lake of Urine, although the various things that need to be done in the run up to publishing a book are distracting.

I published a component part of it a couple of years ago, in novella form, under the title Literature™.

I will call it a novel, I think, if only to help me convince people to read it.

Lake of Urine is published by Sagging Meniscus.

About Erik Martiny

Erik Martiny teaches literature, art and translation to students at Henri IV in Paris. He writes mostly about art, literature and fashion. His articles can be found in The Times Literary Supplement, The London Magazine, Aesthetica Magazine, Whitewall Magazine, Fjords Review, World Literature Today and a number of others.