You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

It’s December 23rd, and Carla and husband Sam are hosting a pre-Christmas dinner party. Guests include Sam’s mother Pat, silver fox Jake and his much younger girlfriend Tamsin, man-hungry but hopeless Hope, and smug Tim and Sophie, parents of their daughter’s schoolfriend.

[private]”We make our own yogurt,” says Tim, quite slurrily, from across the table. “Well, Soph does.”

“Why?” says Tamsin.

“Why do I make yogurt? Well, you know – it’s nice to be self-sufficient, even if it’s only yogurt and bread and growing a few vegetables,” Sophie says. “It’s empowering. And the children love it. Tim and I are great gourmets, you see.” She pronounces the word with a strong French accent. “We really mind about what we eat. We mind passionately. And the kids eat everything we do.”

“Yeah,” says Tim, rather pointlessly. “They do.” He’s quite red, old Timboleeno. He’s drunk.

“That’s great,” I say, which it is.

“My boys were the same,” Pat says. “They ate everything we did. Chips, mostly.”

She hoots with laughter, but I can see Sam practically twitching at the direction the conversation has taken. He is, to all effects and purposes, middle class these days, and he has no issues with most of the aspects of middle-class existence – niggles, yes, but nothing that really tips him over the edge. Except for this one thing: there is a certain kind of approach to eating that sends him absolutely round the bend and that, to him, works as perfect shorthand for everything that is vomit-makingly wanky about the social class he now finds himself occupying. Triggers include: people who say ‘leaves’ instead of salad (see also ‘fizz’, ‘vino’ and every permutation thereof ); people who extol the virtues of X or Y cheese for more than one minute, particularly where they say ‘chèvre’ instead of ‘goat’s cheese’ or specify the variety – sourdough, baguette, focaccia – instead of just saying ‘have some bread’; people who have ninety-five different kinds of vinegar but never the one that you’d want on your chips; people who call chips ‘frites’; people who won’t drink tap water, or – worse – people who will only drink one brand of bottled, because they only like the taste of that one; people with ‘allergies’ who are really on diets; people who order offmenu in restaurants; and any kind of over-thought-out, over-fussy arrangement on a plate. He can’t stand wine bores, on the basis that nobody normal can tell the difference between a £10 and a £20 bottle of wine, ergo they’re just pretending to, like the bourgeois ponces they are. His particular bugbear is people who make too much of the fact that their children are omnivores.

Once, in Italy, we were sitting in a restaurant next to an English couple – overconfident, entitled-seeming, red with sunburn, foghorn voices booming over everyone else’s conversation – who said to their toddler, “Try it, darling, for num-nums. It’s called Parmigiano. Par-meegee-ah-no. That’s right! Come on, try it. You’ll like it. It’s only a tiny bit stronger than Grana Padano, and you loved that, didn’t you? And do you remember the name of the greens you liked yesterday?”

“Puntarelle,” the child said.

Sam grabbed the table, his knuckles white like in a story, and started swearing under his breath – “Get me away from the c**ts, Clara, or kill me. Just kill me.” He’s so good-natured normally that it was quite amusing to see, and I wasn’t as incensed by the display as he was – actually I was rather impressed with the baby’s command of language. But I know what Sam means: there comes a point, with foodie-ism, where you think, “These people are just fetishists,” especially when they see food as the echt signifier of class and social place. There’s a certain kind of eating that basically says, “This is what we do, because we are special and unlike the herd. We are not proles. We make pesto out of ferns and acorns: that’s how evolved we are.” Sometimes we both pine for the days of casseroles and fondue sets, which were a great deal easier to get your head around when you were eating at someone’s house than having to admire people’s perfect, fantastically elaborate recreations of restaurant food – and not just any old restaurant, but ‘fine dining’, if you please. Besides, as Sam points out, he developed his own athlete’s body on a childhood diet of potatoes, tinned food, salad cream and fluorescent fizzy drinks.

“Wouldn’t eat this, though.” Tim points out helpfully. “Spicy. Hot. Hot and spicy.” He leers at Hope as he says this. I silently push the water jug in his direction, trying to catch Hope’s eye, only to find that she’s just as blotto as he is.

“Nice curry,” says Jake. “Quite authentic. I lived in India, you know. For a couple of years, back in the sixties. Man, what a country. What a place.”

“I didn’t know that,” says Tamsin, smiling at him. “How cool. You’ve done such cool stuff, Jake.”

“I know,” says Jake. I suppose when you get to his stage – he must be in his late sixties, though we’ve never been given a straight answer to the question of his exact age – there isn’t much point in modesty or self-deprecation. “I’m rock ‘n’ roll, baby.” This is also true: he is wearing leather trousers, for starters. They’re quite nice, as it happens. Worn in, not all stiff, a description that could, from what I hear, also apply to Jake.

“We should go,” Jake says, putting his hand on Tam’s thigh. “To India. Me, you and Cassie. Take her out of school for a bit. Let her travel. See the world.”

“Broadens the mind,” says Pat, who has travelled to England, Greece (once, with us), Calais and to the bits of Spain where you can get a Full English.

“Exactly, Pat,” says Jake. “Broadens the mind. Very good for children.”

Pat beams at him. “India!” she says. “It’s that far away. Mind, you’d have to watch out for the monkeys.”

“How long would you take your daughter out of school for?” This is, of course, Sophie.

“I don’t know – what do you think, Jake? Three months or so?”

“Three months,” nods Jake. “And if we liked it we could stay longer. Or move on somewhere. Go with the flow, you know.” He is beaming too now, his lined, weathered face split into a leathery, trouser-matching grin. Have I mentioned Jake’s teeth? He has the most improbable gnashers, a full set of crazy, blindingly white, immaculate veneers, purchased at vast expense and a great deal of discomfort shortly after he met Tamsin. It’s like a bathroom showroom every time he smiles – white porcelain as far as the eye can see.

“Three months!” says Sophie.

“No point going for less,” says Jake. “Maybe we should go for longer, Tam. Maybe we should go for, like, a year. Hang out.”

“Cassie’ll turn into a little monkey herself, so she will,” says Pat fondly. “A little brown monkey, like a whatchamacallit, a gibbon.”

I’m not sure I entirely love the juxtaposition of Indian people and monkeys, but I know from long experience that this is a losing battle. There aren’t any brown or black people where Pat comes from, and she marvels every time she takes Maisy to school with me at the multiculturalism on display. Or, as she puts it, the number of ‘darkies’. We had our first row about this, many aeons ago. “Don’t mind me,” Pat had said. “I don’t mean any harm.” And she doesn’t. However.

“I don’t think gibbons are little brown monkeys,” says Tamsin.

“What are the wee brown ones called?” Pat asks.

“Marmosets?” Sophie suggests, looking confused by the turn the conversation has taken.

“No,” Pat says, frowning. “Ah, come on, the wee brown ones. Agile, like. They always remind me,” Pat starts, chuckling affectionately, “of Clara’s friend …”

“Sam!’ I shout across the table in despair. “Sam. Darling. Please.” I flick my eyes to Pat.

“So,” Sam says, bang on cue. “Who’s coming to see my show on the 27th? I’ve offered you all tickets, right?”

“He was a lovely wee dancer when he was a boy,” Pat says to nobody in particular, her mind having – mercifully – wandered away from primates. She takes a genteel sip of her vodka and lemonade. “Loved it. Absolutely loved it. His da and I used to joke that he was a pansy, didn’t we? Oops,” she laughs. “Not a pansy. Oh, it’s that hard to keep up with how you talk in this house. What would you say – a gay? We used to think he was a gay.”

“So you did,” says Sam. “And I’ve always thought you’d secretly like it if I had been.”

“Ooh yes,” says Pat, nodding violently. “I’d have loved it. Well, not then – I’d have been that ashamed. I wouldn’t have been able to show my face. Oh, I’d have died. It was bad enough having to take you to dance classes – I used to cry about it sometimes. The shame, you know.” Sam rolls his eyes, having heard this all his life, though the other people round the table look mildly astonished. “But I’d love it now. Like in Sex and the City! All the gays. Oh, they have fun, don’t they? They have great fun. They’re that colourful.”

“Do you know anyone gay, Pat?” asks Tamsin.

“No, my darling, I don’t,” Pat says, looking pretty cut up about it. And then, seamlessly, “You’d like a gay, wouldn’t you?” she asks Sophie. “One of your kiddies. I can tell. A wee mammy’s boy. A wee gay dote.”

“I …” says Sophie. “Good Lord, what an extraordinary thing to say. I wouldn’t mind a … gay. A gay child. I wouldn’t mind at all. But that’s not to say …”

“Aye,” Pat says. “I knew it. For company.” As I was saying, Pat occasionally has piercingly acute flashes of insight. This particular one has the welcome effect of temporarily silencing Sophie. Tim, meanwhile, is now howling with laughter – an oddly feminine sound – at something Hope, whose breasts are falling out of her dress, has said, and I feel the first twinge of pity for Sophie. The horrible truth of the matter is, you can home-make all the yogurt you want, but it’s not going to stop your husband’s eye wandering.

“Have we finished eating?” asks Jake. “Because I think it’s time for a little smoke. A little doobie. A little blow. Mind if I skin up, Clara?”

I don’t know what’s happened to my supper.[/private]

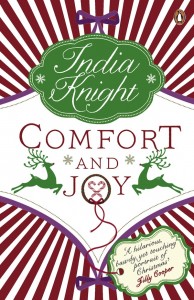

India Knight was born in in 1965. She is the author of two novels, My Life on a Plate and Don’t You Want Me?; a non-fiction collection of essays, The Shops; and a book for children called The Baby. India also writes a column for The Sunday Times, alongside other newspapers and magazines. She lives in London E8 and is a mother of three.

India Knight was born in in 1965. She is the author of two novels, My Life on a Plate and Don’t You Want Me?; a non-fiction collection of essays, The Shops; and a book for children called The Baby. India also writes a column for The Sunday Times, alongside other newspapers and magazines. She lives in London E8 and is a mother of three.