You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

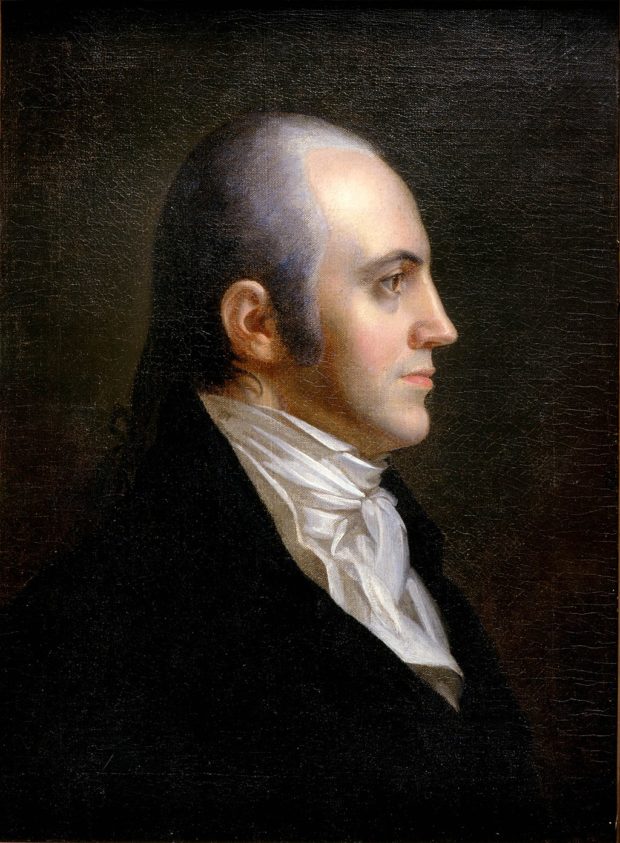

I’ve very nearly finished re-reading Burr – which I thought I’d read forty years ago, but hardly scratched the surface. I was attracted, in the 1970s, to its irreverent feelings as well as the precision of its prose – a distant citadel for which I was hoping to become faintly eligible over time. I had remembered snatches of dialogue, though, when I encountered them a second time, I did not find them any more distinguished than hundreds of others. And while historical fiction is considered the stepchild of true literary eminence, Burr is, by almost any yardstick, a masterpiece that I hope will live on.

Gore Vidal’s familiarity, not only with historical events, but with his characters’ drives and ambitions (he knew as much about the machinery of power as any man who’s ever been hurt by it), is embedded in his every utterance – which is spread out between Charles Schuyler, his everyday narrator, and Burr himself, whose reminiscences form part of a storytelling platform that places us in the twilight of the Jackson era as well as the Revolutionary period which culminated in our independence from Britain, but marches forward, along with Aaron Burr’s multiple triumphs and tragedies. In Burr, Vidal finds a parallel to his literary fortunes, which began with the publication of Williwaw, following the Second World War and spread out, as Burr’s did, quite sprawlingly: with stops in Mexico (which Vidal might have found ironically uncomfortable) Los Angeles, New York City, the European mainland, and, finally, as an expatriate in his beloved Italy. (Italy lasted the longest and was spectacularly nurturing. To it he could escape, ponder the American Empire’s infelicities, and, while grappling with them on the page, stay mostly clear of them in real life.) Compared to Burr’s Staten Island, where he ended his days as the controversial figure he had always been, there was nothing spectacular in an exile that merely happened across the Bay. In the 1830s, however, time and space were rather differently understood. One might never leave a city block unless it was demolished, as was very likely then as now, even if there weren’t quite so many blocks to play with. To leave involuntarily constituted an uprooting our mobility-crazed mentality would – except for the inconvenience of it – hardly notice. In those days, Staten Island might, from Manhattan’s teeming universe – which, as Whitman would later observe about himself, contained multitudes – seemed worlds away. Burr died knowing that. He also knew that, even when he could not hear its echoes, a tarnished reputation would not resurrect itself.

Burr has big-picture virtues as well as the kind that seduce us without our knowing it. It is constructed along substantial lines, but has a familiar, page-turning feel – as if, as with all good stories, it is unfolding on its own good time. Vidal’s stage-setting is beguilingly terse: a few sentences embrace a world-weary spectacle, military stragglers, an unimportant dawn. He is not a poet in this way, but relies on what isn’t said to fill in a panorama that is, because of it, stunningly visualized. (He often condemned the “national style”, which he considered laconically drab. But he can make it work very nicely – even as he might want to move on.) And while his minor characters don’t overcrowd the page, Vidal relishes their presence, delineates them expertly, and manages, by some magical immersion, to throw the mantle of a time and place across them – no matter how long they stay or, with what calculated determination they flee the scene. Our beloved chieftains – Washington, Adams, Madison, and Monroe – are seen as they probably were: men who were occasionally awkward, concealed a fatigue that never went away, and wanted the same things the others did. Which brought the kinds of complications for which novelistic treatments, rather than our ideologically accented histories, are eminently suited. Unlike novelists who have the advantage of studying their models in 3-D, Vidal leans in and breaks whatever fourth wall separates one time period from another. He perceives every private notion as something that will need airing; hypocrisy as a comical end, and regards the rivalries that are circumstantially inevitable to spring up as if the Lord of Misrule were running the show. For Vidal, there are as many unhappy accidents as happy ones. Coincidences may not rule, but they are the friend of ambitious characters. And dumb luck has an extraordinary IQ.

In Vidal’s moral cosmology, common scalawags can be memorable as their betters. Both are after the brass ring; one is, however, more deliciously transparent. And complicated characters, like the philosophical madam who seems, for a time, to rise above the opprobrium of peddling nubile flesh, live fully on the page. Vidal’s breezy skepticism lets myth and reputation (à la Cassio) puncture themselves. It is an antidote for the hero-worship that, in official histories, gets embarrassingly out of hand. For Vidal, the past is something we live in, and with, every day. We’re all “special”, but that doesn’t mean we’re not like everybody else.

This highly political novel isn’t necessarily about politics, but needs them as a sort of matrix. As we learn, Martin Van Buren (“Matty Van”) is likely to become president, as a world-weary Andrew Jackson is about to gratefully retire. That will douse the hopes of the Virginia Junto that has put native-born politicians in the White House for decades. It is a good enough beginning, but there is, because of the principal character’s eventual stamp on things, no more than a minor announcement, such as one used to hear at a railroad station. Vidal’s aims were not necessarily temporal. He aspired not only to re-write history (“History”), but to use it as the cautionary tale it always is. Because we don’t remember it, we’ve had to re-live it, stupidly and agonizingly, down through the ages – ages, in view of what is happening to a planetary system on which we may no longer depend, that may not be available to us again. Vidal wants us to know history as if it were happening all at once: theirs, ours, and everybody’s. If our politicians bear watching, we should watch them. If we live in the short term and itch with the greed our values as well as our natures have bred into us, we should pay close attention. To nationalism and its evil spawn, xenophobia, we should look without favor. And to any form of human slavery, we might consider that, while it gets roads paved and roofs put on houses, it debilitates our morals to the extent that we have no business pretending to be civilized. Burr is Vidal’s plea for us to listen – or one of them. If we don’t, we’ll go back to doing what we did last year. We can’t depend on a tyrant slipping up and telling us what to watch and when. That’s our job. And it is our fate and privilege to do it always.

Rather than concentrate on “what happens”, I want to talk about who actors are always squawking about: character and motivation. Yet, in the interest of performing a conventional service, this is what, in a nutshell, happens: Burr is an old man who has fallen back on lawyering. A law-resistant clerk wants to write and is given the task, by a poet-turned-newspaper editor, to get his boss’s biography down on paper. Over the course of the clerk’s telling, as well as Burr’s, we get a rogue’s progress wrapped in the political life of an emerging republic. Burr as law student, then officer, under Washington and others, is a military disaster that, through the dumb luck that has already been mentioned, actually prevails. Then Burr as legislator, as well as jaundiced observer of politicians who love freedom, but hate democracy. Because of insults that cannot be borne and must be answered in the field, Burr challenges a brilliant upstart to a duel and kills him. Then hides out. After the furor dies down, he runs for president and loses to Jefferson, who has already thrown him a bone nobody has been able to chew properly – the vice presidency – and will do no more. Once he’s out of office – and favor – Burr comes up with an idea that will revive his spirits as well as his political career: he will, with a band of loyalists, invade Mexico and make himself president – no, king (“Yo el Rey,” as he would have liked to proclaim)! – and live happily ever after. But the plot is foiled, Burr is tried for treason, wins the case, goes back to New York and lawyering, then retires. And, finally, on distant Staten Island, he dies.

Now that I’ve dispensed with that, I want to explore some of the book’s many excellences.

By way of upsetting the usual theses regarding the heroic personages we have always cozied up to, Vidal gives us alternative scenarios which are designed to test our patience and, possibly, try our souls. None other than Thomas Jefferson, whose public utterances regarding political life were scathing, turns out to be a consummate politician whose meltdown during his nemesis’ trial for treason dismayed partisans and followers alike. (Jefferson had no case, but pursued it with a teeth-gritting fury.) Traditionally a paragon of those perfections that have allegedly clung to our Founding Fathers to a greater degree than their successors, Jefferson as the statue we would wish to behold has no cracks and is eleven feet tall. Jefferson the man – who was tall enough in real life, but could not be heard in a room full of wooden desks and brass spittoons – was a spot, as the English say, of bother. His dabblings in science and other esoteric fields are, for Vidal, symptoms of an “exuberant mediocrity.” Jefferson’s genius, while tainted, was political. There was no simple truth he could not withhold, or reconfigure. When he appeared to be candid, he was at his most ruthlessly conspiring. He had no small talk, but was spellbinding company. He lived so far beyond his means that he never fought off his losses and, though surrounded by a splendor for which he was outspokenly, if disingenuously, proud, he died a pauper. When he engineered the Louisiana Purchase, he knew it was illegal but was able to do it anyway. (At the time, Americans were united in their detestation of Spanish “dons”, who couldn’t get the hell out fast enough. Privately, Jefferson was in favor of any war that might accomplish this. In his public pronouncements he was, in this as in almost everything, exquisitely politic.) His personality, while sometimes on a lower key than his confederates, was so captivating that Burr himself could not resist it – even as Jefferson connived at his destruction. (Burr saw to it that Jefferson became president, although Jefferson then denied that Burr had much to do with it beyond that of any supporter.) The miscegenation by which he got several children by Sally Hemmings was an open secret and never hurt him, in his life, at all. Jefferson knew that the racism of most Americans would, while initially recoiling at his duplicity, ultimately condone it. Jefferson was, like the kind of Tory he and his fellow patriots drove from American soil in person only, devoted to the privileges of a country squire, for which he needed infusions of cash that were dependent on his productivity as a farmer. He also knew that this productivity was tied to slave labor and made use of it quite (from our way of thinking) outrageously. At the same time, it was accepted without a blink. And so the Great Man lives on – even if his greatness resided in something he had openly repudiated – which is to say, the pursuit and prosecution of public office.

The “Hamilton business” is dispatched with a coolly partisan flavor and, while it made a hero of no one, showed how bitterly divided the country was. Burr could have been arrested for killing another man – which wasn’t officially legal – but he was never tried for it. Indeed. He was, as a card-carrying Republican, admired beyond the Beltway of that era. (Federalists like Hamilton were despised, in the western territories, as shadowy elites.)

Burr’s biographer – who, along with the subject of the book itself, keeps the narrative going – is a Dutchman with appetites that are somewhat bigger than his talents and he is well worth the trouble. (Toward the end of the book, he will learn otherwise.) Through him, we get to know a literary culture which is somewhat lawyerly and leans mostly toward Europe. William Cullen-Bryant is a newspaper editor who loathes the rough-and-tumble of fin de siècle New York City, particularly when it derives from political fevers that are, for him, tragically disfiguring. He preferred the Eratosphere, where his Thanatopsis – which had made him, just barely out of his teens, a very famous young man – would have reigned supreme. Washington Irving’s nostalgia for old Dutch rule is comically suffocating, though he himself is not. (He may be the nicest fellow in literary history – a Robert Benchley for the Ages and a fellow who’d have your back if he could waddle to it fast enough.) Yet for Vidal, all comers are welcome, even when they don’t stay very long. The soldiers, lawyers, frontiersmen, and politicians he trots out of half-empty manor-houses, teeming dockets, forest interiors, and smoking battlefields are all vividly seen, if only transiently important. They’re given their due, according to the design of a sweeping narrative, and live in flashes of sun and moonlight. All are informed by Vidal’s mordant humor, which is loath to make a hero when that hero can so easily stumble. (Not one sits a horse as awkwardly as our Commander-in-Chief.) Speaking of whom: his depiction of The Revolutionary War and its consummate Keystone Cop, George Washington, is so brilliantly catastrophic (Washington never won a battle and was constantly in flight) that one can hardly stand to witness one cringeworthy episode after another. Vidal names the real heroes – which would include Burr himself – who have not been completely lost, but who were not household words then and cannot be now.

The young America out of which the world power of a century and a half later emerged is, in Vidal’s rendering, surprisingly familiar. The factions that so troubled post-Revolutionary politicians have always been among us, and have always thrived. And while the rule of law is ostensibly respected, the higher law of the jungle is more frequently in force – and enforced as well. If we want to overthrow the country, we’re bad fellows, but if we do it in the guise of something noble, we might happily reduce it – as we have to much of the Middle East – to scorched earth. Burr represented a kind of enlightened autocracy, which has elements of the frontier. Eternally restless, Burr, who, while intellectually precocious, believed in action over word, was ready to start a new republic where the roots of civilization – which had, by his late forties, already withered and died – could take root for the first time and flourish just as they might have in Europe. Like many Americans, he believed in a kind of self-invention that could, over a lifetime, become, like a tree-trunk’s telltale rings, infinitely layered. If, over the course of one year, you did this, you might try something else during the next. His vitality is America’s vitality, albeit tempered with an understanding of cause and effect. Burr was a calculating man who knew how destructive vaulting ambition was and thought that, if he could rule, he might be able to curb it. Perhaps he could have. We will never know.

Ultimately, Burr is an American tragedy, seasoned, however, with a resilience so incredible that, if there are any heroes in the book, he’s pretty damned close. And, as much as I loathe Andrew Jackson for tearing Native American communities apart for the sake of gold, he emerges as a sensible hothead and a maniac you want on your side rather than the other. As a historian, Vidal was a lifer. And while Burr is a milestone not to be missed, Vidal had so many tricks up his sleeve that, try as we might, we will never discern the sleight-of-hand, which is not so much invested in fooling an audience as in telling it what the magician feels it absolutely must know.

About Brett Busang

Writing provides all sorts of people with an opportunity to not only fall back, but to spring forward. Melville needed to be broken by the sea to find a better place in the library. Mark Twain - who was christened Somebody Else - chose a mighty river on which to fail - though the river failed him first. He managed, however, to bounce back. And took the name by which we know him to help guarantee that. Me? I wanted to be a scientist, then athlete, and, finally, a musician. And after my troubles with these, I started to push small words around. Whom should God help first, me or you?