You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

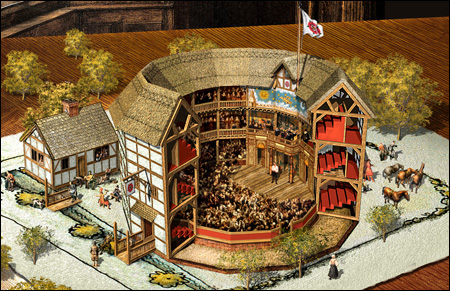

The Rose Theatre in Southwark is an astonishing venue. Audience members are crammed into a narrow, damp, cold space, unheated and sparsely lit. In any other theatre, there would be numerous complaints. But here, minor discomforts are easily forgiven: the Rose is an archaeological site and the audience is seated above the remains of one of Britain’s oldest playhouses. Lit by a chain of tiny red fairy lights marking the outlines of the theatre, the excavations reveal the shape and dimensions of the historic stage where many of Shakespeare’s early plays were performed.

Today’s Rose is a working theatre, and it is a popular performance venue, staging everything from opera to obscure Elizabethan tragedy, with an understandable emphasis on Shakespeare’s plays. But on this occasion, the focus was not on the drama performed at the Rose, but on the excavations themselves. Chaired by eminent theatre historian Andrew Gurr, this panel discussion between four archaeologists revealed what digging up the remains of London’s outdoor theatres can tell us about plays and playgoing in Elizabethan London. The audience was invited to imagine a hidden world buried beneath the modern-day capital: an unnamed early theatre lies, inaccessible, below the Elephant and Castle roundabout, while the remains of the Curtain Theatre in Shoreditch have just recently been excavated and will be preserved in the basement of a new development. Beneath the offices and restaurants of Southwark lie bear-baiting arenas where animals fought for the entertainment of spectators, taverns where actors and audience members drank, and, of course, the original Globe theatre, some metres away from today’s popular replica.

Andrew Gurr observed that the Rose Theatre is “unique, and uniquely important” because its foundations have been recovered in their entirety – this is true of no other theatre from the period. The completeness of the foundations has made it possible for archaeologists to discover how the theatre was rebuilt, and the stage extended, in the mid-1590s. Theatrical impresario Phillip Henslowe, who owned and ran the Rose, made extensive alterations to his theatre, both to increase the possible size of the audience and to alter the shape of the stage. Thanks to the survival of Henslowe’s extraordinarily detailed diaries, which record transactions with playwrights, actors’ debts, lists of costumes and props, and box office takings, historians were already aware that Henslowe modified the Rose; what the archaeology suggests, through revealing the exact shapes of the two stages, is the reason why. In changing the layout of the stage, Henslowe was catering to recent developments in drama, making it easier for his actors to deliver soliloquies and asides to the audience. As archaeologist Julian Bowsher remarked, the new stage created “a more intimate experience” for the audience; Henslowe was responding to the literary fashions that would eventually result in Hamlet’s intimate soliloquies. By combing archaeological discoveries with surviving documents, Bowsher showed that we can gain far greater insight into the workings of the early modern theatrical world.

One of the talk’s strengths was that it did not confine itself to theatres, but brought to life many aspects of London life. Archaeologist David Saxby discussed his excavations of the “Bear Garden”, a popular alternative to the theatres for an afternoon’s entertainment. An average performance at the Bear Garden might include watching six or seven dogs attack first a bear, then a horse, then a boar, and finally, a “jackanape”, or monkey, attached to a horse’s back. It is easy to forget that at the same time Shakespeare’s Hamlet pondered his mortality onstage for the pleasure of audiences at the Globe, a bloodbath of animal slaughter attracted similar audiences nearby. In later years, the programme at the Bear Garden expanded to feature polar bears, tigers and even humans: audiences gathered to see a butcher fight a baker, a candlestick maker fight an embroiderer of silk scarves and even, on one occasion, at eating contest between two locals. These matches are described in written records, but what Saxby emphasizes is the way that archaeology can flesh out the abstract and impersonal nature of historical records with concrete, personal items that give a sense of the realities of the period. Archeological discoveries at these sites include a prop sword, fragments of the Rose’s box for theatre takings (the origin of the term “box office”), pieces of clothing, and a pewter tankard marked with the name of the “Keeper” of one of the bear gardens, which has turned up in excavations of a local tavern.

The archaeologists were all extremely knowledgeable and passionate about their subjects; occasionally, the discussion became rather too detailed and specific for a general audience, with talk of load-bearing walls, relieving arches and much focus on exact measurements and dimensions. From the detailed and informed questions that concluded the panel discussion, I would imagine that there were many keen amateurs in the audience, so perhaps I was alone in finding the plethora of detail and use of jargon off-putting. The speakers provided some fantastic images of their excavations; Heather Knight showed photos of her work in excavation “trenches” at the site of the Curtain Theatre over the last couple of weeks, as well as a new 3D model of Richard Burbage’s “The Theatre”, one of the very first Elizabethan playhouses. However, there were a number of issues with locating the right images throughout the evening, which quickly became wearing, and the white glare of the projector detracted from the atmospheric venue. But these are minor complaints. Overall, this was a fascinating and thought-provoking event, showing how theatre archaeology can bring a hidden, underground past to the surface, and illuminate the lost world of the Elizabethan theatre.

About Emma Whipday

Emma is a PhD Candidate in English at UCL, researching violent homes in Shakespeare's tragedies. She studied at Oxford as an undergraduate, where she was deputy editor of The Isis. Emma has written for the Royal Opera House Digital Guide to the Winter's Tale, the Newcastle Evening Chronicle and the Sunday Times Culture Magazine. She is the Associate Writer for theatre company Reverend Productions.