You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

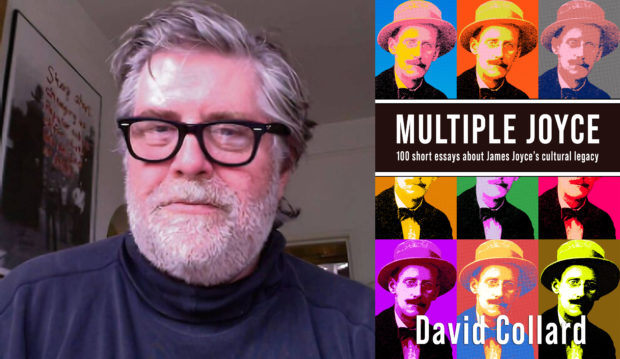

David Collard writes for print and online publications including the Times Literary Supplement, Literary Review, 3:AM Magazine, gorse, Exacting Clam and White Review. His book About a Girl: a Reader’s Guide to Eimear McBride’s A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing was published by CB editions and he contributed to the recent anthologies We’ll Never Have Paris and Love Bites.

His latest book, Multiple Joyce,marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of Ulysses and investigates the writer’s cultural legacy through 100 short essays. Conducting much of his research on the internet, Collard finds connections between Joyce and unlikely sources such as Kim Kardashian, Cher, Hattie Jacques and The Ramones.

Katy Ward: Thank you for speaking to us today. I really enjoyed the book and thought the details about Joyce’s life you included were fascinating.

David Collard: I’m very glad to hear it. You’re the first, shall we say, civilian reader of the book that I’ve met. This is the first conversation I’ve had about it with a reader!

KW: To start with the obvious question, what is it about Joyce that led you to write the book?

DC: It’s an obvious question, but a very good one. Joyce’s life, chaotic and unstable as it was, is fascinating. It’s a model of how to live as an artist, sponging off others, spending money on yourself selfishly and drinking too much. That’s always interesting, but it’s the works really – the works are inexhaustible, gifts that keep on giving.

Anne Enright said that no one has ever finished reading Ulysses because it can never be exhausted. You can read Mrs. Dalloway, say, and it stays read, but every time you go back to Ulysses, it has more to offer.

He’s also a writer for a lifetime. I realised when I first encountered Joyce at school that I’d be reading, and rereading, him for the rest of my life. He’s always there, waiting for you to catch up. I first read A Portrait of the Artist when I was pretty much the age of Stephen Dedalus and now I’m old enough to be Leopold Bloom’s father.

KW: You wrote much of the book during lockdown. Did this alter your approach to writing and research?

DC: I thought at first it would be a terrible constraint. I couldn’t go to libraries or use archives and I couldn’t even leave the neighbourhood, apart from trips to the post office and supermarket. And the off-licence. But it turned out to be a liberation. Because I could access only online material, the book rapidly became 100 essays about Joyce’s cultural legacy on the internet. He’s got well over a million online citations, second only to Shakespeare, so there’s no shortage of material.

I was three days into writing when I did something rather silly. I typed “James Joyce + Kardashian” into Google. I wanted to find something incredibly popular that was unlikely to have any connection to Joyce. Lo and behold, something really unexpected came up [an app that likens Kim Kardashian’s writing style to Joyce’s]. The essay practically wrote itself.

I started entering things like “James Joyce + Kierkegaard”, “James Joyce + SpongeBob SquarePants”, “James Joyce + Susan Sontag”, and feminism, and football, and alcohol, and Triesteand so on. You get a prize every time.

That wasn’t how I wrote all the essays, but it was a starting point for many of them. As a method, it’s not respectable or academically legitimate, but I’d recommend it. You could do a book about any writer using this approach, but it’s especially interesting for Joyce, because he is everywhere. So my book is a kind of preliminary audit of Joyce’s cultural legacy as it appears online, or mostly.

KW: How has your reading of Joyce changed over the years?

DC: In some ways, it’s got much easier. I’m figuring out what I like about Joyce, rather than trying to live up to his expectations of me. The older I get, the more I admire Dubliners, which seems like the simplest of the books, but it’s also the most humane and generous. It beggars belief that he wrote it when he was in his twenties. He knew the human heart. I don’t think you get so much of that in the later books but, in Dubliners, you get affections and emotions to an extraordinary degree. It’s supernaturally mature.

My reading has become more selective. Now I’m older I don’t feel under any obligation to read anything that doesn’t hold my attention. I read other authors, but Joyce is one of the two or three writers I always need to have to hand.

As you get older, the first sign of real maturity is being able to say no to people. My reading maturity came when I realised that I don’t have to read Finnegans Wake and I don’t have to be ashamed of not reading Finnegans Wake, because I’ve read Ulysses enough times to feel quite secure in my feelings about Joyce in general and that problematic book in particular.

A very distinguished critic once told me that they had never read a page Ulysses, but they had read all of Finnegans Wake. Perhaps it was meant to shock me, or to prove a point, but I find it inconceivable that anyone would read the Wake and not Ulysses.

KW: I read Finnegans Wake at university, but I was too immature to understand it.

DC: Is it a question of maturity? Perhaps Joyce’s books should all carry a ‘best-before’ date. You should read Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist before you’re 20 and then Ulysses between the ages of 20 and 40. Then after that, Finnegans Wake, if you want. Maybe you should read the works at the same age that Joyce was when he wrote them.

The great thing about Portrait is that we can read it when we’re the same age as Stephen, but we have the great advantage of having the novel to read, and he doesn’t have that. It’s a great book if you need to escape from the shackles of family and religion.

KW: It goes back to what you were saying about heart and emotion. I think that’s what makes us relate to Stephen perhaps more than some of Joyce’s other characters.

DC: Certainly in A Portrait. In Ulysses, not so much. And his appeal isn’t gendered, is it? Stephen isn’t just appealing to teenage blokes, is he?

KW: No, I think the book touches on the teenage stage that everyone goes through, regardless of gender.

DC: There are many very distinguished female Joyceans, but the world of Joyce scholarship seems still to be predominantly male. I don’t think there’s quite such an imbalance when it comes to readers. I don’t have any statistics on that. It’s just a sense I get.

KW: My next question is the one that I was most interested to ask you. Which of the misconceptions about Joyce do you find the most frustrating?

DC: There’s a very well-intentioned view that Ulysses is a novel for everyone. It’s not for everyone because, unless you live under some tyrannical government, nothing is for everyone, whether that’s athletics, romantic fiction, Netflix or whiskey.

Ulysses isn’t for everyone, but – this is my point – it should be for anyone. That’s an important distinction. There shouldn’t be any barrier to access, but that doesn’t mean you have to force it on people. It’s a very sophisticated book, and challenging, and it’s not for the reader who wants a plot and characters they can relate to and so on – the usual expectations. Ulysses raises your game. It makes you into an above-average reader if you get to the end of it.

I tend to lose patience with people who think they can bring Ulysses to a general audience, especially those editors who think “Oh, if I just simplify the punctuation a bit and if I remove the compound words…”

I find that incredibly entitled on their part, and it irritates me. Joyce knew what he was doing, and he did what he did. We should absolutely respect that. And be wary of interventions.

KW: I wouldn’t dare as an editor.

DC: Absolutely. And with it, come all the other popularisations around Joyce, including Bloomsday. Putting on straw hats and getting drunk is great fun and we should do it every day, I’m not against it all, but I also want to re-mystify Joyce as a very great novelist. We should bring ourselves up to his level as readers, rather than bringing him down to ours as celebrants. I just want to defend his integrity as a writer and artist and not see him as an excuse simply a pretext for a booze-up. Although there’s nothing wrong with a booze up! Some writers need defending from their admirers.

KW: Which I think is a nice segue to my next question. What advice would you have for someone approaching Joyce for the first time?

DC: I’m a very bad person to ask for advice. I’d say, first of all, there’s no obligation at all to read Joyce, or any other writer. And without sounding glibly paradoxical I’d say don’t approach him for the first time, try to approach him for the second time. Some wit said that you can’t read Ulysses; you can only reread it. I think that’s true. Read it once to find out what it’s about, then read it again and again to find out what it’s for and how it’s done.

For the newcomer I recommend starting with Dubliners. There are 15 stories, so you could read one a day for a fortnight. It will be the best fortnight’s reading you’ll ever do.

A lot of readers flounder when they get to episode three of Ulysses, with Stephen walking along the beach with his eyes shut and the ‘ineluctable modality of the visible’ and so on, and it’s often when they read the phrase “agenbite of inwit”. We all encounter this term for the first time in Ulysses. I remember looking it up and thinking “Oh, that’s the Medieval term for remorse. He’s using it because his mother is dead and because he’s a pretentious young man who is a lot smarter than me.” It’s far easier now to look up any problematic word or phrase or episode on the internet, and you come out of Ulysses with a much larger vocabulary than you went in. Someone once said that Ulysses is a book that creates the kind of readers that Ulysses needs. There’s a lot in that.

KW: One of my favourite characteristics of Multiple Joyce is the way that you include details about your own life, and your experience of growing up in a Jehovah’s Witness community. Were you comfortable sharing details about yourself?

DC: Thank you. I’m not the kind of writer to share personal things, but I’d reached a point in my life when the circumstances of my childhood were haunting me. And I included something about this because it also explains my psychological barrier when it comes to reading Finnegans Wake. The commitment Joyce expects from you as a reader of Finnegans Wake is the same thing I had to put up with as a kid in a fundamentalist Christian sect. I do share moreof myself in the book than I normally would and there is stuff in the book that people close to me don’t know. I finally managed to get it down on the page, and this was partly prompted by Joyce’s honesty. The only subject I know more about than Joyce is myself.

KW: There is something cathartic about putting something out there into the void.

DC: That’s very true. I’ve set down everything that I want the world to know about that aspect of me. A very good writer called Ali Millar has a memoir coming out later this year called The Last Days [that covers her experience of growing up in a Jehovah’s Witness community]. This means I don’t have to writemy own novel about fearing the end of the world in an environment where everything is either forbidden or compulsory.

KW: It must have been terrifying as a child, all the talk of Armageddon.

DC: You spend your life recovering from it, but it never really goes away. Writing about my childhood is a way of coming to terms with that part of my past, and my formative years. I felt it added something personal to the book that you don’t always get with books about Joyce.

KW: It added something for me. I felt as though it was different genres coming together.

DC: I hope it also suggests how much Joyce meant to me on my first encounter with Portrait of the Artist. When Joyce writes “a cold lucid indifference reigned in his soul”, it spoke to me. It was like becoming Icarus. Joyce forged me the wings to fly – and crash.

KW: Was there anything you learnt in researching the book that surprised you?

DC: I was simply astonished by the extent of Joyce’s legacy on the internet. It’s practically impossible to find something that doesn’t link to him. I’ve got one exception in mind though, and I want to create a link through our conversation appearing online. “James Joyce, + Suzi Quatro”. I was quite a fan of hers, so I wanted to get her into my book, but there was nothing that connects Suzi Quatro to James Joyce.

KW: I hope we can create one. In some of the essays, you express concerns about whether Joyce will have a significant readership in the future. Can you say a bit more about that, please?

DC: It’s more of an existential concern as to whether any of us will be around to read in 50 years, given the clusterfuck we’re in. We’ve got climate change, a war in Europe, Brexit, the threat of nuclear annihilation and pandemics. Any of these could prevent a long-term audience for any novel.

A few years ago, I met a very bright producer who had just started working at the BBC. They had a degree in English from a very good university and told me they had never heard of TS Eliot. Fair enough – you can’t read everything and I’m certainly not criticising them. How can you have a degree in English and not come out with TS Eliot at least as a reference point? It’s like doing chemistry and not knowing the periodic table. You might not approve of Eliot, but you can’t deny his centrality to the 20th century as a poet and critic. And if Eliot isn’t secure on the curriculum nobody is.

KW: I would have thought that anyone would have heard of TS Eliot through osmosis.

DC: And likewise, Joyce. Joyce is read not by an elite, as some detractors claim, but by a minority. A lot of readers first encounter him at university, and to an extent it’s academics who keep him afloat and in circulation through conferences and papers and so on – and the academy is changing. We’ve long since questioned the idea of a canon and the privileges of that canon, and that’s a good thing.

I don’t think Joyce will be knocked from his perch for any kind of ‘woke’ or revisionist reasons. I don’t think there is anything to discover that would discredit him, as there is with almost every other modernist. But at the same time I just don’t see anything in culture as being secure or immune from changes in taste and priorities for academics. I have a concern – and it’s central to my book – that Joyce is for many not so much an author to be read, as opposed to a cultural presence to be celebrated. He takes a lot of time and effort, yet we want quick results in this click culture, don’t we?

KW: How will you be marking Bloomsday this year? It’s obviously the date of Multiple Joyce’s publication.

DC: I’ll be in Dublin for the launch at Hodges and Figgis on the 16th June. I’ve got a few friends in Dublin, who I hope will form a human shield between me and the audience if I face any criticism as a presumptuous Englishman coming over and gassing on about their local hero.

The actual centenary of the publication was earlier this year, on Joyce’s birthday, February 2nd. For the past three years I’ve hosted a weekly online gathering as a platform for writers, poets, publishers and creative practitioners. It’s like In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg after three martinis. For the centenary, we had the Joyceans Clare Hutton and Finn Fordham, and the Dublin soprano Elizabeth Hilliard, and performances and film, and the opening of Ulysses read in Greek, and a tour of Glenn Johnston’s astonishing Joyce collection in New York, and a whole bunch of other stuff. So that was how we marked the actual centenary, but as I say on Bloomsday this year I’ll be in Dublin for a few days for the launch and having a few drinks and mucking about with friends.

KW: That feels like a great place to end. Again, I wanted to say how much I enjoyed the book.

DC: I’m so pleased to hear that – thank you!

About Katy Ward

Katy Ward is a short story writer and journalist based in the north of England. Her fiction, which has been published in various journals in the UK and US, focuses on the themes of addiction, social class, and shattered relationships. As a journalist and editor, her work has appeared in numerous national newspapers and independent media outlets.