You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Daughter to Mary Wollstonecraft, the eighteenth-century radical feminist and political philosopher, and the controversial philosophical anarchist William Godwin, little Mary Godwin had a lot to live up to.

Nevertheless, she was undaunted by the reputations of her parents. Even as a teenager, the aspiring writer not only embraced their ideas, but embodied them in her way of life. Mary Shelley, a biographical play at the Tricycle Theatre, co-produced by Shared Experience, Nottingham Playhouse and West Yorkshire Playhouse, revolves around her early years before she was known as the author of Frankenstein, starting from the period of her life shortly before she met the “vibrant” Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, becoming his itinerant lover, and eventually, his wife.

Literary fans of the protagonists’ work will be disappointed. The play engages little with their writing and far more with their passionate impulses, which induce the self-centered Shelley to abandon his pregnant wife, encouraging Mary to run away with him at the age of sixteen, becoming an unwed mother in the process. She further flouts convention – and her father’s wishes – by taking her stepsister Jane along for the ride. Together, the threesome ramble across Europe, experiencing the highs of love and depths of tragedy.

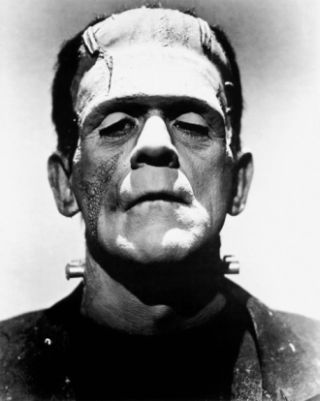

For material so passion-soaked, the first half drags. The play is too long, and its most interesting ideas – how to carve out an authentic life irrespective of social mores, the fight of the personal versus the political, the yielding to change that maturity requires – are overshadowed in favor of adolescent melodrama. Consequently, the play ends up less powerful than it might have been: a three-hour soap opera that skims over its protagonists’ literary achievements and progressive politics. The play barely alludes to Frankenstein, since the story ends before Mary, at the age of 19, writes the book that is to become, arguably, the first science fiction novel in English literature.

That would be fine, if the characters merited interest irrespective of their real-life achievements. But parentage and literary fame aside, their actions (in this play, at least) reduce Mary and Shelley to self-absorbed, irresponsible hedonists. They make a virtue of doing what they want, regardless of the consequences on others, and though they seem happier following their hearts and not society’s rigid rules, they leave devastation in their wake and, ultimately, end up compromising their ideals when they decide to marry.

The characters might make a stronger case for romanticism if the performances were more charismatic. Kristin Atherton as Mary is spirited, but shouty at times, while Ben Lamb lacks the presence and magnetism of a man meant to have inspired so much swooning. In the supporting roles, Flora Nicholson as the eldest sister Fanny is suitably uptight, quivering, mouse-like, with oversensitivity, while Shannon Tarbet as Jane is amusingly – if irritatingly – affected, high on romantic notions yet determined enough to see them through. (Mary Godwin is not the only one in this play to get knocked up by a famous poet.)

For all its melodrama, Mary Shelley stays broadly true to historical facts, and the play provides an insightful window into these writers’ backgrounds. Typical of the work of Shared Experience and artistic director Polly Teale, there are moments of beautifully staged, physical representations of the characters’ feelings, including Mary’s yearning for her mother, who died shortly after childbirth, and her wrenching pain over her infant daughter’s death, poignantly evoked when the baby’s swaddling clothes unravels to a white sheet that trails away into the wings, leaving Mary empty-handed.

Helen Edmundson, who wrote the play (as well as other stage adaptations of The Mill on the Floss and Anna Karenina), has wrought an imaginative, if overheated, drama from early nineteenth-century lives, and the effect is akin to Twilight with historical instead of supernatural trappings. The schoolgirls in the audience sounded engrossed, at least, squealing at the love scenes and gasping in horror at one of Shelley’s predictable transgressions.

Mary Shelley lived courageously by both the heart and the head, but this play, unfortunately, emphasizes too much of one over the other.

Mary Shelley continues at the Tricycle Theatre through to 7 July. Watch the trailer.

About N/A N/A

Melanie White is an arts writer and editor who returned to London in 2011 after eight years in the US. In addition to journalism, she has written two feature screenplays and is currently working on a novel. Contact her at melanie.caro.white@gmail.com.