You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The first question everyone asks when I say I’m attending an exhibition on the subject of the megacity is, ‘What exactly is a megacity?’

The Oxford dictionary definition:

- A very large city, typically with a population of over ten million.

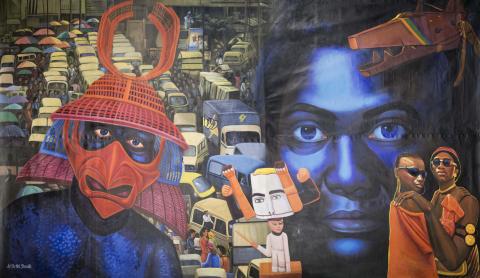

This definition, although obviously correct, fails to evoke the unifying characteristics of a megacity: pollution, traffic, a rapid increase in population, sprawling housing development, abject poverty, unimaginable wealth, labyrinthine public transport systems and in relation to this exhibition, exciting and flourishing art scenes.

The five megacities showcased here are: Dhaka, Lagos, Manila, Mexico City and Tehran.

The curators are keen to point out in the program, however, that the megacity provides the exhibition’s context but not its content. Indeed, part of their objective is to create a space that is not categorised by geographical location nor “defined by origins or borders”.

This aim is evident in the layout of the exhibition, detailed in a fold-out A3 map found at the entrance. Works are displayed in no particular order, and artists often have several pieces spread out amongst the two floors of the museum. Having to navigate such a large space with so many mediums: painting, video installation, fashion design, photography and robotics to name a few, has a dizzying effect. I suspect this is deliberate, creating the dynamic felt in major cities: a sense of claustrophobia mixed with the collective energy of ten million+ people living in close proximity.

*

Ndidi Dike’s recreation of Lagos market stall part photo collage, part sculpture, takes up a corner of the first room, appears cluttered, but look closer, see that – as the artist herself puts it – the stall is “aggressively arranged”: piles of fabric and rolls of ribbon are displayed according to colour, Tupperware boxes are neatly stacked, brooms are lined up in neat rows, bowls of chillies, fluted pumpkins, tomatoes, and African monkey kola are placed precariously one atop the other but show no signs of teetering, packet noodles, almonds, beans, sieves, white plastic spoons, everything has its place, everything belongs, crouch down and place myself within the picture, move to Dhaka, Bangladesh, Britto Arts Trust, artists paint domestic objects, same techniques used for city rickshaws, bright and deep pinks, blues, red, oranges and greens, exhaust pipes, frying pans, teapots, parasols, fire extinguishers, a lion sips tea while chatting to a pigeon sitting at a table in a town square, rickshaw art is dying out I tell my daughter, being replaced by digital images, humans by machines, ‘the art is being lost?’ she asks, crestfallen, plonks herself down in front of the exhibit, draws a sketch of a frying pan portrait, looking, not through a mobile phone lens like so many museum goers but following lines with her eyes, turn the corner to a corridor of work, stop at Farrokh Mahdavi’s portraits of pink figures that cover three walls, the floor, daughter runs straight in, Paris-street footsteps on paint, the guard says “Madame, vous pouvez y aller”, it feels strange to walk on work, to add to the accumulation of dirt that blurs the image, the paint is thick, the colour of stuck-to-your-shoe bubble gum, his muses are bald, old men, young men, women, babies, clown-like smiles, Mahdavi worked in a morgue, makes sense, despite the brightness of the pink and the smiles, the portraits are morbid, fleshy-molten masks that much like the Mona Lisa seem to follow you around the room, we walk out, stumble upon a vast space, black advertising board at its centre, one giant slogan, IN A BOTTLE, CITIES ARE ALIVE, look for meaning, look for bearings, think of “message in a bottle”, walk past walls dripping spray-paint neon pink and wood-chip partitions, black and white photos by WAFFLESNCREAM, fashion brand ads, skateboards, men, thick-biceps, arms crossed, muscles flexed, angles, elbows, wrists, tight T-shirts, strong bodies, puffed chests, clasped fists, find a room full of earth, a mechanical horse that looks dead, put down, skeleton made of wood, hollow body nothing but a plastic bag, lifts its head, mane and tail intact, thick, black, daughter takes comfort in one fact, it can still move but it is laboured, no breath, turn, walk head down, bump into costumes like clowns, the white mannequins and harlequin colours of HA.MU, a Manila fashion brand, artists are young, born in ’96, ‘this one is the least weird,’ says my daughter, pointing to a red confection the shape of a real heart, can we touch she asks, there are multiple arms, rubber gloves, knitted appendages, rainbow slinkies where there should be limbs, hidden faces, bare legs, is this the front or the back? she says, we climb steps to discover the body of a whale on the floor, a work by Bikini Wax EPS, its ribs stripped clean, its head still slick and black, as well as its tail and fin, reminds me of a piñata, dropped, gutted, full of candy-coloured knick-knacks of American consumerism, 90s paraphernalia, childhood toys gone wrong, Gremlins, Jaws, Mickey Mouse in a graduation cap, a surrealist clock, a dinosaur with broken legs, the whale has been gagged by Coca-Cola cans attached to a rope, a telly in the corner shows clips of Free Willy, crowded aquariums, whales attempting to turn in containers too tight, children bang on glass, they want more, we take the stairs down to another floor, huge papier Mache strippers apply lipstick, pour themselves a drink, naked except for high heels and lingerie, hair long, lips thick, can’t remember if there is a warning about graphic content, wonder what is graphic about a woman in her underwear applying lipstick, pouring herself a drink, is it the stance that might offend, the nonchalance, legs apart, legs crossed, we walk past Newsha Tavakolian’s video installation of women from Iran singing, but the sound has been turned down, think of my theatre tutor’s most common phrase for critiquing, “short fuse”, the impact fizzes out too quick, we all know women’s voices are supressed but what are we going to do about it, we are tired now, maybe jaded, take a seat downstairs before entering Doktor Karayom’s room of red and white illustrations wall to wall, a sculpture of a man lying on a plinth at its centre, his body opened up like an anatomical model from secondary school, layers of epidermis, red, raw, pink, the body inhabited by tiny men the size of toy soldiers, a macabre enactment of Lilliput, scaling his veins, his eyes still open in shock, my daughter is not frightened but I feel overwhelmed by sounds, sights, glare, glitter, too tired to traverse the hallways and board Emeka Ogboh’s yellow bus and the call of voices, loud echoes, that if I’m totally honest intimidate me, because the space is badly lit, like an alleyway behind restaurants where no-one’s supposed to be, an underground car park in the stomach of the city, my daughter wants to keep going so we continue but only manage one more exhibit on the lower level, same shape as a skate park, slope leads to a sculpture that is small, ring-shaped like a hollowed out slice of an oak tree turned on its side, small magic, like fairy tale toadstools, a neon bar of light, textures and colours oozing into each other, nail polish red, New York taxi yellow, greens purples and blues of the clothes of Disney’s seven dwarves, shiny and matte, Mehraneh Atashi’s kaleidoscopic cavern like a child’s imagination, danger lurking round the edges, my daughter strides in front of me, not fatigued by the overload of senses of this reconstructed city of art that lives and breathes, suffocates and blossoms in your mind, minutes, days and hours after you leave it behind and step outside onto a Paris street and feel both constrained by the city, and ultimately, free.

About Anna Pook

Anna Pook is from South London. She obtained an MA in prose fiction from the University of East Anglia, where she was the 2014/15 recipient of the Man Booker Scholarship. Her work has been longlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize, published in the Mechanics' Institute Review, and will feature in a forthcoming anthology of megacity fiction from Boiler House Press.