You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

An Introduction

I am a man of many rituals. One is that I like to go for a jog, or at least a walk, before I write anything. Another is that I try to eat a fancy lunch on Fridays. I think it is perfectly normal to do things regularly, in a manner that appeals to you, and to be petty and particular about it. I do not think this makes a person superstitious, or untrue to their nature, or out of touch with the world. This morning I ran around Kennington Park, so that I could write this.

Since moving to London in September, I have reserved Sunday afternoons for going to the cinema alone. It is my favourite day of the week. At present I have two jobs: a sit-down day job and a stand-up night job, both of which conspire to fill the one hundred and forty-four hours between Monday and Saturday. When I wake up with a headache at the end of the week, I check the film listings online, shower, pack fruit, books and paracetamol into a bag, then close the latch on my still-sleeping flat. I slowly make my way through town in the direction of my cinema of choice (I go to a new one each week), stopping on the way to read, drink coffee and make notes. Present yet barely awake.

For some, going to see a film alone is taboo. Like throwing your own birthday party, or waiting for a friend at a busy junction staring into space, rather than fiddling with your phone. Loners in the aisles are viewed as a perversion, indicative of a deep social malaise, soaking up the company they could not earn without a £9 entry fee. After a series of solo screenings, I find this view increasingly difficult to comprehend. The cinema, after all, is not a sociable activity: you should not talk, or eat (despite what you might think), or do anything that might disturb the people sitting next to you. No social markers survive the journey through the box office into the theatre. There is nothing to discuss: only darkness, anonymous bodies and a sense of time having stopped – how many times have you asked, “When did it get dark?” after emerging from a film. It is the best way to be in a crowd in the city.

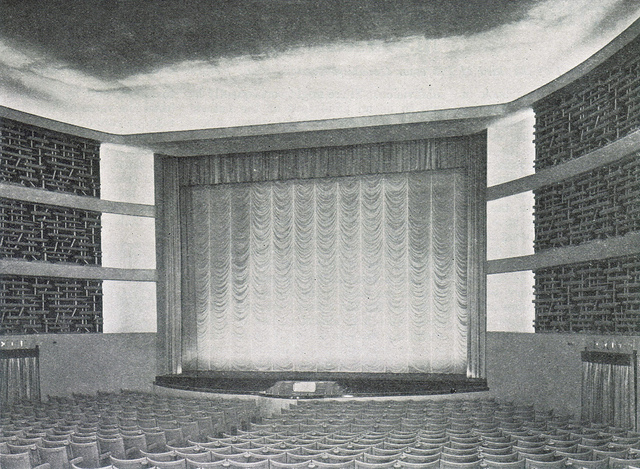

When I was growing up, the conventional wisdom was that art was meant to “take you out of yourself”. But the paraphernalia that comes with the experience of going to the movies ensures that despite the constellation of moving images and sound, you never truly disconnect from your thoughts. The auditorium is a long classical-style hall with plaster panels and columns, I thought, last Sunday. It is old. Perhaps it used to be a theatre. I could not be sure, so I made a note to Google it that night.

When everyone had left, I put on my things and sauntered through the cold in search of a bus. I had no thoughts about the film at that point, just a moody “stickiness”, which I enjoyed. I did not want to go home, so I stopped to drink a Coke and eat some food, putting off the double-grind, the traffic, lack of sleep (I was, even then, half-asleep), the tedious necessities and everything else that waits for me outside the cinema.

The Electric Pavilion

When the Pavilion opened on Saturday, 11 March 1911, it was considered fitting that the largest of cinema developers Israel Davis’s new projects should be situated on Electric Avenue. It was, after all, the first street in London to be lit from end to end by electricity. The auditorium held seats for seven hundred and fifty spectators, and housed an organ, proscenium arch, gilded cherubim and parallel pilasters, sending ornate plaster beams in arcs across the dark red roof. Ushers served ice cream and peanuts and champagne.

The area was modernising. Older attendees recalled a time when this part of Surrey was nothing but a series of lanes, the dank River Effra and Ashby’s flour mill rising in the distance. Now the old houses were being broken down into flats, and there were terraced houses stuffed with growing families from Vauxhall—and even further afield, Cornwall, Ireland, Lancashire—all in need of entertainment; if they could afford it.

Everyone stood for the national anthem. The organ pipes let out a hollow gasp. There was a loud applause and nervous chatter, then quiet, as the Electric Pavilion—later Pullman (’54), later Classic (’64), later Little Bit Ritzy (’78), today the Ritzy Picturehouse, or Cinema—began its life in monochrome. They came as couples, families, assemblies of notable dignitaries and elected officials, minor royals and businessmen. Meanwhile some enthusiasts, who had made arrangements and thrown off other responsibilities, came to mingle in among the heaving crowd alone.

About Philip Maughan

Philip Maughan was born in Middlesbrough in 1987. He currently works at the New Statesman and blogs at philipmaughan.tumblr.com.