You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

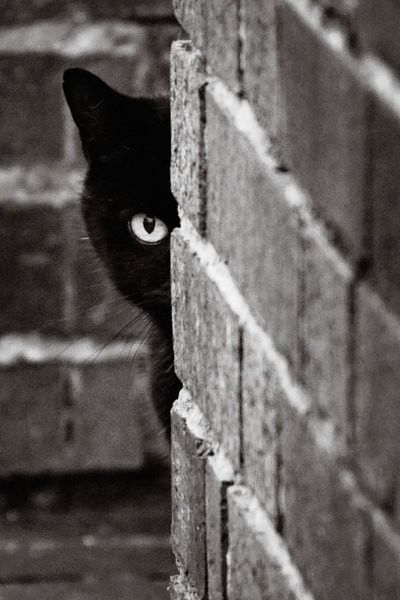

Imagine a cat, a stray, that became a woman every sunrise, a fierce black-haired woman named Lucia, who marched through the streets as though she owned them, although she was, in fact, homeless. In brown rags Lucia made her rounds, burst into restaurant after restaurant favored by the wealthy, stood aggressively close to the tables with their plates of sweet rolls and eggs and smoked fish. She thrust out a filthy hand and demanded money.

“You with your soft bellies, and me hungry. You can spare it!”

Her boldness was so shocking, so different from the other beggars in town, who kept humbly and quietly to the street corners, that most people complied with a coin or two, if only to get her to leave. Most that is except one old man, new to the city, Nico the rug dealer, with skin as rosy as ham, hair dyed the color of charcoal, angry blue eyes, and rings on every finger.

“Go away, you dirty slut,” he told her. “Shoo!”

“A little change is nothing to you,” Lucia spat back. “Those rings alone! And,” she hissed on tiptoe, leaning close, “if you lost each and every one, you would still eat, you old shit.”

Nico turned purple. Snapped his fingers and shouted at the wait staff. Two of them escorted Lucia roughly out. Her luck was bad that day – she collected scarcely enough for a small roll of bread.

After that Lucia searched for the old man. She relished a battle. It pleased her to enrage – it was, often, the only time people looked her in the eye. A few days later, she found old Nico eating stuffed trout under a green umbrella. This time, his eyes showed fear as well as rage. The waiters hustled Lucia away, but she savored victory nonetheless. The old man wondered how she’d tracked him down, she was certain of that. She chuckled as the waiters thrust her into the street. “I’m a hunter, you’ll never escape.”

That evening, right after sunset, when Lucia was once again a skinny black cat with golden eyes and a proud tail, she happened upon the lush garden of the enormous house that belonged to old Nico. She visited gardens throughout the city every night, lapped water from their fountains, hunted tiny mice and large crickets, slept curled on tiles still warm from the sun.

She wound her way along the high wall, daintily avoiding the broken glass mortared to the top, leaped to the branch of a jacaranda tree, shimmied down the trunk, and cautiously explored the perimeter of the garden, her ears alert, claws pricked in case there was a dog.

Instead, to her surprise, there was old Nico at a table on the patio, drinking a glass of sparkling wine, his bejeweled fingers straying now and again into a bowl of fat, salty nuts. His face sagged, the skin gray without sunlight. His thin hair was the dull black of a chalkboard. Only his blue eyes gleamed, like another pair of jewels. They watched the cat as she settled at the other end of the patio and began to groom herself. He smiled at her. Him! Lucia’s skin tightened but she kept working at her tail. He was, she saw, the sort of man who prefers cats to people.

What had made old Nico this way? Perhaps it was the nasty business of dealing in rugs. Decades ago in one of those difficult countries, he’d seen mothers sell their own children. In this place, he’d found his servant, Mezar, and taught him how to make a bed, set a table, and decant wine. Now that Nico was old, he and Mezar had come to live in this small pink city at the edge of the sea.

The old man called out to Lucia, his puckered mouth making noises somewhere between a kiss and a squeak. She ignored him, licking dust off her sleek belly. The garden smelled of jasmine and bird droppings. There was a pedestal fountain, and flowering vines, and glowing lanterns, and rows of thick hedges that contained the shadowed darkness she relished.

Nico finished his wine and gave a shout. Lucia, tracking the shy stink of a mouse behind a potted plant, froze, but it was Mezar he shouted at, a tall, strong man who came up quietly and poured more wine, and a few minutes later returned with a saucer of cream. Old Nico instructed Mezar to place the saucer at the edge of the patio, close to the cat but not too close. “Don’t scare her!” Mezar, dark and unreadable, studied the cat with his yellow eyes, and went back inside.

Lucia’s furry jaw hung open as she smelled the cream. She would wait to drink it until Nico left – safer that way. Several times, people had attempted to trap her with a lure; she’d escaped just in time. But once she completed her bath, she decided to tease the old man, who, now that she was a cat and not a woman, suddenly wanted to be friends.

Nico had finished his wine and gazed at the sky, at the faint stars that struggled to be seen in the city twilight. Lucia bolted across the patio in a sudden streak, and the old man shrieked like a hen. Slowly she circled back, approached his chair, and flicked her tail against his bony shins.

“You sly creature!” Nico cried. “Come, come.” He patted his lap.

She looked at him steadily, walked away and delicately lapped up the cream, her ears flattened backwards the better to detect a stealthy approach from behind. He seemed too slow to sneak up on her, and the servant was inside, but Lucia had been around long enough to know carelessness can be fatal. The cream was delicious, so sweet and fatty, and there was a lot in the saucer. She had not tasted anything so good in a long time. When she’d licked up every drop, she felt quite sleepy.

Old Nico himself appeared to be dozing. His eyes were closed, his head sunk to his chest, he had a thick blanket draped over his thighs. Up she jumped, claws sinking into the wool.

He yelped, and Lucia’s fur stood on end as she flew back into the hedges.

“No, no, come back, sweet!” he called. “My deepest apologies,” he said. “You startled me that’s all.” He patted his lap and danced his fingers across the blanket. Perhaps she should have jumped over the wall then and there, but the bellyful of cream made her lazy. Instead, she hid among the hedges.

He called again and again, but all cats know how to hide so they can’t be found. She heard the servant clearing the table and picking up the dish she’d licked clean. Mezar tried to coax old Nico inside where it was warmer.

“In a moment,” the old man said.

When Mezar had gone in with the dishes, Nico creaked up out of his chair. His slippered feet slapped the tiles and crunched on the gravel paths. He called out again with mouse-like kissing sounds. “I’m sorry I frightened you,” he said. “I’ll leave my window open in case you want to come out of the cold. My bedroom is up there, on the second floor.”

He was inviting her to sleep with him! Safely hidden, Lucia rolled onto her back and laughed as only a cat can, silently, invisibly. “Fat chance,” she thought.

But after he’d gone inside, and the patio doors closed, she reconsidered. She’d not had a good night’s sleep in years. Even in the walled gardens where she preferred to spend the night, she must always be alert – on the lookout for dogs, other cats, large rats, insomniacs, early risers. Imagine a real bed, a real mattress! She couldn’t. She’d never slept in one. As a child, she and her mother dozed on straw. The old man was rich. His bed would be soft, warm, safe – too bad he was in it. She would look, just a peek.

She climbed the tree and from there saw an open window she could reach only by jumping through a space twice as long as she was, landing with a thump and scrabble on the ledge. Which she did. She peered into a large, dark room.

What a bed it was – enormous, canopied, curtained, a row of pillows lined up behind old Nico’s head like fat geese. His eyes widened and gleamed. They watched one another.

“Welcome, lovely!” he said, and patted the brocade bedcover.

Lucia stayed where she was. The room smelled of another cat, not a recent scent but ancient, from months ago, or maybe years. It smelled of the musty, perfumed old man. It smelled of lavender and pine. She didn’t trust it.

She watched as the old man slid deeper under the covers, and turned to one side, where he sighed, belched, and began to snore.

Night after night, Lucia visited, drank the cream, allowed the old man to scratch her furry neck, and hunted crickets and mice in the hedges. Sometimes she perched in the window and watched him sleep. There was never anyone else in bed with the old man; he always had the whole enormous mattress to himself.

Several times, quite late, she slipped into the house and ran silently through rooms filled with rugs from around the world. Archways, tiled hallways, sofas, and in one room a terrifying piano with black and white teeth. She investigated the toilets and sniffed the rugs, in which she detected donkey piss, cigarettes, goat milk, spilt coffee. She killed a cockroach or two.

Mezar the servant slept downstairs in a narrow bed off the kitchen. Even in his sleep he scarcely made a sound, his breathing deep and smooth, except when he dreamed and his eyelids twitched. Then, sometimes, he whimpered or snarled. He was handsome, with thick black hair and sleek muscles, but Lucia was afraid of him, a being so consumed by duty he seemed to have no desires of his own.

She always jumped out the window long before she felt the need to curl up, and always scaled the garden wall long before sunrise. There was a particular warm spot on the tiles where she liked to doze until the early hours, when the clatter of the garbage trucks told her it was time to leave, and where, on the other side of the wall, a pile of brown rags lay waiting to cover her.

Days, Lucia made her usual rounds. Her human hair was thicker and shinier from the daily bowl of cream. Not as hungry or as tired as before, her pleas were softer, and, strangely, coins poured into her hands. Instead of plain rolls, Lucia bought herself sandwiches piled with onions and grilled meat. A sliver of padding emerged along her ribs and narrow hips.

Now and then she spotted old Nico in a restaurant, always alone, glaring at other diners with his blue eyes. She no longer approached him in her human form, no longer had any desire to expose his ugly side, which lay right on the surface anyhow. She crossed streets to avoid him, and he didn’t even notice.

Late one night it rained, a downpour. Cold and drenched, Lucia jumped onto Nico’s windowsill. She made certain he was asleep, listening to his snoring before she entered. She investigated the edges of the room with its many odors, rubbed her wet fur on the Turkish rug, licked herself clean where dirt and leaves clung, blinked.

The old man was sitting up in bed staring.

“Well, hello,” he said, groggily but also gloatingly, a seducer who knows his victim has at last succumbed.

Lucia hissed.

“All right,” Nico said. “Never mind. Do as you please.” He turned onto his side and closed his eyes. She walked a circle on the rug, curled up. Wind blew in through the open window. Icy rain spattered the tile floor. She couldn’t sleep.

At last, she slipped under the heavy gold curtain onto the soft bed, the brocade quilt pleasantly rough against her fur, the mattress so soft it gave her the strange, almost frightening feeling of floating. The old man, though bony, was warm, a sharp heat, and the warmth reminded her of sleeping with her mother as a child. His scent when asleep was different, heavier, blurry, another blanket. She curled closer and closer, he under the covers, she on top, until they lay back to back.

She woke once to the old man stroking her fur. He whispered, “I think we shall become friends.” He lay a hand on her head, scratched it expertly, and began to snore. The vibrations were soothing. Despite herself, she purred.

In a moment, I’ll go, Lucia thought – as soon as the rain stops. The bed was so warm and so soft. Impossible to stop purring, impossible to stay awake. She kneaded the covers. If he tries anything he shouldn’t, I’ll scratch his face.

It rained all night, it didn’t stop. Because of this she overslept.

Morning came, cloudy, the sun floated higher; its dim light fell through the window and touched the bed. Lucia smelled the hot skunky odor of coffee brewing, opened her eyes, and found herself face to face with the old man, whose own eyes sprang wide.

“What the hell?” he shouted, his morning breath hot and foul. “You hussy! How did you get in! In my bed!”

Lucia scrambled away, the tile floor slick and slippery with rainwater. Impossible to spring out the window in her current form. She could already hear Mezar running up the stairs.

“You idiot!” she shouted back. “You invited me. That’s right, you left your window open for me night after night, fed me cream, called to me in those silly mouse squeaks. What a stupid, stupid man you are.”

Nico’s mouth hung open, his wrinkled hands plucked the quilt, his blue eyes were cloudy marbles. He tried to speak but all he said was, “Gah,” as if he’d had a stroke.

Lucia snatched the old man’s robe to cover herself.

Mezar arrived – tall, strong, angry – and grabbed Lucia’s shoulders and pushed her through the house, a mouse hooked to a claw, helpless. The house looked different through human eyes, all the colors, for one thing – the hallway was green, the bathroom red, the piano golden brown. A rich but treacherous place. She told herself it would be the last time she would ever visit.

Mezar shoved her out the high metal gate, a shove that sent her to her knees. “I don’t take kindly to trespassers,” he said. “Next time, I call the police.”

Insults quivered on her tongue but she kept them in her mouth. Police were everywhere in the wealthy neighborhoods and she knew how rough they were. Mezar wiped his hands on his trousers as if touching her had soiled them. He slammed the gate shut.

She stood, dusted off her scraped hands and knees. Immense walls on both sides of the street, the only signs of life maids and gardeners plodding up the hill to work. A police jeep slowed as it approached and she started walking.

It seemed as if she must still be asleep. The wet streets gleamed. The purple robe was light but warm. She reached the park and sat on a wet bench. Such a terrible old man, and his servant no better. Stunted, selfish, unhappy people. But the bed, the bed had been lovely. She’d never slept so well in her life. She closed her eyes and remembered the brocade quilt, the bloated pillows. She sat so still that after a while small birds began to hop along her knees and shoulders. Carefully she opened her eyes, admired their fluffy, juicy lightness. Her mouth watered slightly. Little innocents, they had no idea.

Of course, Nico’s window would no longer be left open. And, if it was, she couldn’t trust it. The two men could be plotting – a trap, a cage, a sale to the circus, as her mother had threatened whenever Lucia displeased her.

She slept in other gardens after that, under chairs, and inside sheds, hiding the robe somewhere safe for morning. She wandered the dusty outskirts of the city where people were poorer and thus more generous. She couldn’t say how she’d come to be the way she was because it was the way she’d always been.

Nico looked for her. Something like that should be locked up, studied, dissected. How dare she sleep in his bed under false pretenses! He hobbled from the center to the waterfront and back again, needing a cane to support his right side, weak from the shock of that traumatic awakening. He searched for a glimpse of wild black hair, his purple robe. He couldn’t find her, though daily he sat, waiting, in the very same restaurant where they’d first met. And as he waited and stirred his thick coffee, sipped a bittersweet aperitif, ate dumplings and slices of cake, strange thoughts entered his mind. He remembered her face that morning, how she’d looked neither cunning nor fierce but shockingly young and innocent. Her slippery, peeled nakedness. He tried to remember what he’d said to her and couldn’t. He remembered her eyes, amber, cat’s eyes.

He wondered what a life like hers was like, one animal by day, another by night, how lonely, so lonely. He himself was lonely.

Weeks went by, the rain heavy, and he worried. Perhaps the strange creature was dying or dead. What if one day he stumbled upon a hairy heap of black, neither woman nor cat. Should he try to save her? And for what? He’d seen the look in her eyes. She would kill him and laugh about it afterwards.

That winter was long. Nico drooped. He began to bite his nails and scratch the insides of his ears. His limp grew worse. He decided he needed a cat, a nice one that would sit on his lap. He sent Mezar searching for a kitten, and Mezar brought them home, little balls of energy – a gray one, an orange one, a tabby. But they never stayed. Their little tongues protruded as they smelled Lucia’s powerful musk, imperceptible to humans, an odor that told them that she was strong and ruthless, that this place was hers, and off they fled to other houses, other lives.

Spring came at last. The cherry trees in the park exploded with white blossoms, and Lucia trudged back into the city. She’d eaten nothing but stale bread and mice all winter. The padding around her ribs had vanished, her hair was dull, her skin ashy, the purple robe had faded to mauve. She smelled asparagus and peas, spring milk and sardines. By now, she hoped the old man and his servant had given up looking for her. She was hungry and tired of hiding.

The fizz of pollen, sweetness in the air, the longer days. People were distracted and generous. Lucia collected enough coins that morning to buy a cone of fried sardines from a corner pushcart. She took it into an alley to eat secretly, beggars should never be seen eating, and devoured the lovely crunchy fish, bones and all. She licked her greasy lips and continued down the thoroughfare. But a full stomach can dim the senses, make you careless.

Nico’s sharp blue eyes saw her before she saw him. He limped hastily out of the restaurant with his new jeweled cane.

They nearly collided. “Come back,” he said hoarsely. “My home is your home.”

No one had ever said such a thing to her.

Lucia sneered. “So you can trap me in cage.”

He paused. “No, no!”

Which should she believe – his words or the pause before them?

Lucia ran. Nico followed, making a fool of himself in front of everyone. But she was fast and he was slow. She disappeared among the alleys.

Nico ordered Mezar to search for Lucia. “Cat, woman, cat,” he stuttered, repeating this again and again, waving his hands. Nico handed Mezar a gold ring. “When you find her, give her this.”

Mezar believed the decline he’d feared for some time had come. He slipped the ring into his pocket and left it there. His fervid sense of duty was crumbling like rotten wood. When old Nico died, Mezar would be out of a job and a home. He had no intention of hunting for this cat-woman or woman-cat or whatever she was. Look at what she’d done to Nico. The old man could scarcely talk, and sometimes, worst of all, he wept. No, Mezar didn’t want to go anywhere near that silky skin, that silky fur, alarming things he’d spent a lifetime avoiding. He tucked Nico in at night and helped him out of bed in the morning and changed the sheets when necessary.

Late one evening, as she trailed the scent of roast lamb, Lucia found herself back on Nico’s quiet street. The truck and its portable grill had vanished, leaving nothing behind, not even bones. What a trial this stuffy neighborhood was! She’d seen no sign of either Nico or Mezar since Nico’s disturbing invitation, although she’d been particularly alert in case one or the other might sneak up behind to clap a net over her head. If only the two had vanished along with the truck of roast lamb. She sniffed at the base of their wall, not detecting much. Perhaps they’d been swallowed by Nico’s piano or maybe they had floated away on the enormous bed.

Curious, she climbed onto the garden wall and hid behind the purple jacaranda tree, ready to flee in an instant. The garden smelled of roses, a rat or two, the brief tenure of the kittens. A saucer of cream waited on the tiles. Lucia watched as Mezar helped the old man to a chair and swaddled him in thick blankets, although the night was warm. Nico was slowly dying, a strangely calming thing for a cat to witness.

She stayed hidden, as the old man was helped inside and to bed, as Mezar brought in the bowl of cream and swept the patio. She watched as the second-floor window opened. Listened as Mezar turned out the lights and whimpered in his own lonely bed.

What harm could they do to her now, these two sad creatures, one near death and the other weak with fear? Lucia trotted along the wall, along the long branch of the tree, and leaped. She jumped into the bed, sniffed at Nico’s cold nose and wrinkled ears, and nestled herself against his warm back. She slept all night. In the morning she stayed.

Was old Nico happy at last? It was hard to tell. He no longer spoke, his eyes were dim, but when she sat on his lap, his face relaxed and he scratched her neck. Who knows what his life might have been like if he’d been kinder sooner. In no time at all, Lucia gave birth to a vast litter, all of them fond of Nico’s quiet lap. No one knew who the father was. Was it Mezar, whose step was lighter, who sometimes even smiled as the children banged on the piano and tussled on the rugs, or was it old Nico, although that was hard to imagine, or had Lucia managed to produce her children through another kind of magic? She herself wasn’t saying, having become plump and languid. She drowsed and dozed and ate, curled in the garden with sardines and cream and pillows, as her lively offspring scrambled up the jacaranda tree and over the garden wall, sparkling through town.

About Rosaleen Bertolino

Rosaleen Bertolino's fiction has most recently appeared in New England Review, Vassar Review, Storyscape, and Blood & Bourbon, and is forthcoming in failbetter and several anthologies. Born and raised just north of San Francisco, she now lives in Mexico, where she is a founder and host of Prose Cafe, a monthly reading series based in San Miguel de Allende. She has just completed a collection of short stories and is at work on another.