You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping You have never seen so many snow globes, not all in one room, not like that. He picks one up, cradles it in fingerless gloves and says, See?

You have never seen so many snow globes, not all in one room, not like that. He picks one up, cradles it in fingerless gloves and says, See?

He inverts the globe and the black flies swarm around the figurine. It clutches its head as it disappears behind the swarm. The legend reads “PLAGUE,” the face screams “NO!” and you laugh. You move your leg, just a smidge and it is touching his. It’s hot, even through the corduroy, through the stocking, through the skin. Even with your heart clutched close.

And you can’t look at him now so you look around the room. Every surface is covered in these breathless orbs, bulging like camera lenses and ripe with secretive worlds. You think about crawling inside to where it is quiet in the water, until everything tumbles and the universe is filled with flecks of white, glitter, and ash, hurtling like departing galaxies. You wonder how to tell him, how to move, how to tilt closer for your lips to meet. His face is distant, as if he’s tucked behind these layers of glass. And then he reaches to your chin with a thumb and pulls you inside.

*

Donald perches on the corner of the table, neck arched, taking lustful swigs of Rolling Rock. He is surrounded by the fawning. They tell him he cinches the punctuation of gravity, he grasps the sugar of spheres. They look at his sculpture of the glass lung, the capillaries spun in spider webs, blossoming like baby’s breath, and they clutch at themselves and sigh. He does not talk much because he does not need to; it would spoil the illusion besides. He waits without fervor, waits stoic as a magnet while they whirl closer.

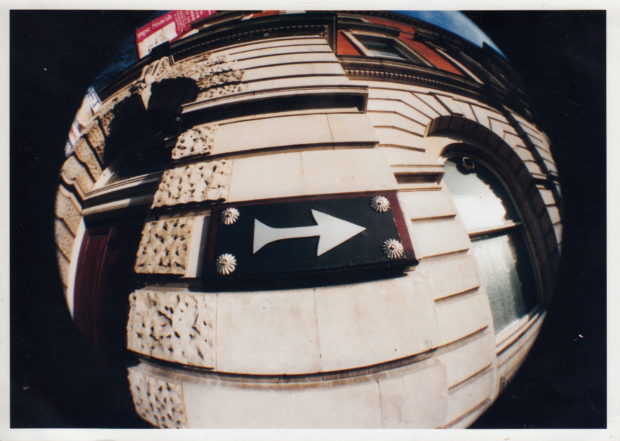

Monica doesn’t need to talk to him—doesn’t care—she’s only here for the free booze anyway and has seen enough fools to know that it doesn’t take an angel to sing like one. All the sculpting in the world won’t connect your hands to your heart, that’s right, and it doesn’t matter that he’s beautiful: she’s seen enough pretty boys too. She looks at the bell jars and the baubles, surfaces pearlescent as bubble mixture. It feels as if the whole room would shatter if she sneezed. Monica holds her breath and checks her reflection. Blunt fringe, blackened sockets, a pout like a snap from a fish-eye lens. She nods abruptly. Lookin’ good, Monica. Lookin’ good.

It takes the toilet queue for their orbits to cross. Monica fidgets, though it takes more than glitz and façade to impress her and it doesn’t matter that she can see sapphires lodged in the blink of his eyes. Now Donald doesn’t start a conversation because Donald doesn’t initiate, but when it looks like she will keep her lips firmly bitten, turn and clack her heels away, he changes his mind fast and grabs her arm.

“There’s more at home, come on.”

He steers her into the lift shaft and pulls the grate closed. The mechanism rattles and they plunge.

*

It is a week later and you are on his arm. He may look rawboned and delicate, but it is a powerful arm: an anchor that grounds you to the room. It is this arm you cleave to as the crowds swoop and murmur. You cannot keep track of conversation, the constant wash of people like the froth and foam of lapping waves. But this doesn’t matter much; you are aglow. Surrounded by the ones whose sticks beat the drum for the foot soldiers to follow. You have arrived.

The party bobs along merrily and you are not really convinced about your body anymore, by what it’s doing. It could be the tiny pink Alice pill he tucked under your tongue or the kiss that said, “Hush, you.” You hold on and he looks pensive while they talk and talk and tell him who he is. You watch the crowds whirlpool and think of a brush daubed heavy with cerulean and teal, wiry ink figures leaping from the canvas. Their chatter is a parade of silver jagged brushstrokes dancing to the top right corner. Squint and you’ll see it. Quietly, you wait until he is ready to go home, then you let him lead you there.

*

Donald takes her out of the lift and into the taxi and soon they are in his Tribeca apartment, cluttered with a forest of snow globes. Monica juts out her lip like she isn’t impressed so easily. She tells her mind to shut it, glances around, concentrates on a spattered wall hanging. Donald watches with amusement as she twitches, then takes her by the chin and kisses her.

As soon as their lips touch, they drop the cool, no longer required to tuck away their desires to make themselves palatable. They claw at each other, rabid with the taste of saliva and skin, like sharks at the first sniff of blood. There are teeth marks in the soft of his collar, spasmed fingers clutching fistfuls of hair. Street noises rattle through the gaping window and the air is downy-soft September. Donald pushes her to the bed and falls on top. His fist is stronger than it looks as it closes around her wrists. Her cry is subway-car brakes shrieking on the track. A kiss on the tip of her nose and she falls asleep sticky as the sun is rising. Donald closes the curtain and wraps protective arms around her.

*

Months shuffle past. Tonight is the third party this week, the same crowd, the same rules. You keep waking in his apartment later and later in the day, losing the morning, letting the hangover nibble into the afternoon. Most of your time is spent padding around in his flannel shirt, drinking countless stale coffees and blowing plumes of smoke out the fire escape. Trying to rid your head of this dust. His bed is cramped and gnaws your muscles, while the six a.m. ceiling stares back at you.

By the time you awaken properly, he has mostly left for his studio. You struggle to remember how you used to fill time and try to muster your enthusiasm for painting. Your inclination harrumphs like an old horse led out for one last dressage. The brush twitches but each line is so obvious and so mortifying the blood rushes to your cheeks in an empty room. His press cuttings cackle from their frames. Piss off. You crumple the papers in the bin and pack an empty orange carton and newspaper on top.

Sometimes you take the train back to Brooklyn and walk around the apartment, looking to your pictures. Wanting. After the exactness of his lines, yours seem to stumble. In moments, there is something in them and then, again, there is nothing. You stand poised with the brush until the light shifts to grey and the shadows lengthen and it is time to catch the subway back.

Most often, however, you are wedged in torpor, as autumn slopes into winter and outside looks like a threat. You stir restless until his return, upon which he plies you with kisses and places the pill inside. And you step out to where the world is happening.

*

Donald and Monica are together. This is not something that was discussed, and that suits them both fine. Neither seems to have much stomach for heavy emotion and this, what they have, is easy. She slipped into his world like a Cinderella who found the shoe, and she stumbles along in it while his arm keeps her steady.

They are the prettiest couple on the scene. She is candy on his arm and she is sweet as glucose, sweet as the powdered fairy dust they sniff. The glorious droplets of dreams, the salt shaker in the conjurer’s kitchen, the glitz in the spritzer that turns her breath to bubbles and her skin to silk. Donald and Monica have found their epicenter. She clutches tight and takes a breath, a deep one, for the road.

*

Except. Except you are bored. You watch them swirling round you, telling Donald he is wonderful, and you are bored. Floating bored, giddy bored, light-as-eiderdown bored. It doesn’t matter how deep you sniff, you’re not floating free. You are hooked on him, hooked to the ground.

But hey, this is a party, so you look to the DJ, waiting to hear that song you love. The one that tastes like lavender frosting on a Sunday afternoon. You’d request it and it would set your limbs free to frolic, but your brain’s circuits are stuttering and it’s his cadence that is lodged in your head.

*

Another party and Monica is wasted, crazy wasted. She took too much, the boy who owns this basement had a handful of heart-shapes, glowing like first love in his palm, and she ate and she ate and it was good. It made her walls undulate, turned the ice-cubes sterling silver in her cup. The cyclone around them changes direction whenever she blinks. People spin into corners on ladders of synthesizer keys, their toes lighting up each step. Monica hiccups.

This is a party, right, so Monica drums her fingers on her thigh, thumbing an offbeat, watching her hand tango. And then some guy comes over, some guy with, “Hey Donald! How’s your new project working, those apothecary bottles, maaarvellous!” Donald deigns to agree, starts to expatiate on his theories of form. His arm is becoming an anvil. They are the centre of attention the way that a bug is, trapped under an upturned glass before a circle of schoolchildren. Monica kicks an exploratory toe, but the world does not shatter. Nothing happens. Donald talks on.

*

You try to hum it but your lips forget what they’re forming. The gin tastes astringent and too full of fizz; the bubbles explode beneath your skin in pins and needles where his arm touches yours. You keep on thinking about fingers uncurling. About running. About streetlights. About different ways to escape.

*

Monica picks a flake of dried skin from her cuticle and folds a lock of hair like a concertina between her fingertips. Her ankle begins to twitch. She cranes the arch of her foot while her eyes flit from face to face.

People move around the room, directionless and inane. They shift like numbers from a traffic algorithm flickering across a screen. They talk about nothing. Or perhaps about something else. Monica can’t hear them, anyway.

She raises a hand to her hair, pushes it from her brow as if easing into a searing bathtub. As Donald remains planted in position for the guests to pay court, her eyelids begin to droop. She hears the word “brilliant” for the sixteenth time; she hears the word “incisive” and it sounds like teeth. Then, before she can pause and doubt and reconsider, her arm slithers from his like a balloon’s string from the fist of an unobservant child. She finds the balls of her feet, turns from his side, and into the thick of the storm.

*

When you release the anchor, you flutter to the surface, dodge the tangle of music, totter towards the stairwell door. You clatter up the stairs, pushing the doors with both hands, letting your body fall through. There is a tightening in your throat and you feel like your lungs have solidified and turned to brittle, cracked glass. You struggle to inhale and then you push the door to the street open and step outside into the icy night.

*

Donald looks down to his empty arm and up to the swinging door, and the sentence he holds outstretched turns frangible in his mouth. His words shatter and fall to the floor.

Around him, the guests are quiet. They are ready for the next thing that will come from his lips.

*

And it has started to snow. The softest first snowfall, snowflakes so hesitant they can barely let go of the sky. You close your eyes and tilt your chin, and they cover you like the kisses of bumblebees. The crystals cling to your cheekbones, soften, and run down your face. It feels like the tracks of tears, though you’re convinced that your lips are smiling.

About Jane Flett

Jane Flett is a philosopher, cellist, and seamstress of most fetching stories. Her poetry features in Salt’s Best British Poetry 2012 and is available as a chapbook, Quick, to the Hothouse, from dancing girl press. Her fiction—which Tom Robbins described as “among the most exciting things I've read since social networking crippled the Language Wheel”—has been commissioned for BBC Radio, awarded the SBT New Writer Award, and performed at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Visit her at https://janeflett.com.