You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Riots for Stravinsky and cheers for Hanatarashi. How do you get from the tritone as “the devil in music” to an audience facing a wall of white noise with smiles on their faces?

“It’s amazing, really, how little sound comes out of something you’re smashing with all your might” – Yamatsuka Eye

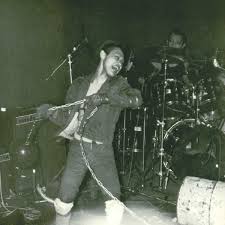

The adventurous Noizu fans who came to see crackpot noise-makers Hanatarashi (meaning snot-nosed) at Tokyo’s Toritsu Kasei Super Loft on August 4th 1985 expected a raucous show. What they didn’t expect was a ferocious performance of industrial-grade destruction, with a back-hoe bulldozer as the lead instrument. Handed waivers upon arrival that relieved the band of any responsibility for injury, or worse, the audience watched as frontman and HDV operator Yamatsuka Eye burst through the doors of the hall atop the bulldozer. With percussionist Ikuo Taketani somewhat safely tucked away in the corner, Eye tore through the stage and inflicted brutal punishment on everything nearby, including the literal kitchen sink, while screaming the band’s trademark scatological and sexual non-sequitur lyrics. The beleaguered bulldozer held out until Eye put the hoe into the wall. The dozer tipped backwards and gave out, but after pulling off the dozer’s cage to hurl across the stage and grabbing a circular saw, the destruction continued with the audience now nervously dodging Eye’s fitful saw swings. Surrounded by bent metal, crumbled masonry and the squawking remains of Marshall stacks, with gasoline pouring from the ruined bulldozer, Eye produced, as his grand finale, a molotov cocktail that he’d prepared earlier. This was a touch too dangerous for even this daredevil audience and Eye, confessing later in an interview for Banana Fish Magazine that he got “too excited”, had to be violently subdued by several members of the crowd.

In the settled atmosphere, once certain that explosive group immolation wasn’t to be the crescendo, the crowd that had remained, many with smiles on their faces, slowly filed out enclosed in their own bubbles of tinnitus. The bill for the annihilation of the Super Loft tallied ¥600,000 (approximately £6000) and Hanatarashi subsequently laboured under a ban from most venues that ran until 1990, when the band, slightly calmer and more safety conscious, dropped the ‘i’ and returned to what passed as civil society in the Noizu circuit.

Hanatarashi, along with fellow Noizu bands such as Hijokaidan, indulged in the kind of audial assault that would bring most people to the point of self-induced deafness, but the Super Loft audience signed off on possible death-by-bulldozer just for the opportunity to experience it up close and personal. Extreme volume, distortion and cacophony, with a ferocity of performance that completely transgressed the normal bounds of the relationship between the performer and audience, were unrestrained musical expressions that attracted large audiences to the Noizu scene in Japan from the 1980’s onwards. It’s been argued that Noise as a genre was born in Japan at this time; whereby the noise was not a wash or flavour, but the whole. The act of seeking out sounds which most people take care to avoid seems a strange masochistic ritual, but evidenced by the brutalised crowd at the Hanatarashi gig, there is – for some – much to enjoy in noise.

“I did Noise Music because I genuinely liked noise… But a lot of people didn’t. At my concerts, people smashed beer glasses in my face.” – noise musician Boyd Rice a.k.a NON

In music, the definition of noise has changed drastically over time and is still debated today. The simplest common usage of the word noise is that of unwanted sound and, although clearly subjective, in some sense this definition also works in the context of music. Noise in music is of a volume/tonality/structure which breaks from previously held traditions of what is ‘pleasant’ to the ear of the average person, or consonant. What may be considered at the time to be noise can be the sound desired by a particular composer and, one would hope for the composer’s sake, later embraced by the intended audience. In essence, history has shown that noise in music is unwanted until a musician proves otherwise, with help from a willing audience. Noise can be a disturbance, but disturbance can be key to progression. By prodding at the edges of the normative discrimination, musicians have expanded the appreciation for sounds which previous generations would have found genuinely violative.

‘Who wrote this fiendish “Rite of Spring”? What right had he to write the thing?

Against our helpless ears to fling

Its crash, clash, cling, clang, bing, bang bing?

And then to call it “Rite of SPRING,” The season when on joyous wing The birds melodious carols sing And harmony’s in every thing!

He who could write the “Rite of Spring,” If I be right by right should swing!’

Anonymous letter to the Boston Herold of February 9, 1924

An amusing example of how dissonant prodding has been received as violative is to be found at the Paris première of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs- Élysées on the 29th of May 1913, the year that the Ford Motor Company would develop the first moving, mass-production assembly line. Stravinsky was a young and innovative Russian composer, of little renown in 1913, hired by Sergei Diaghilev’s to write for the Ballets Russes company, with The Rite of Spring being the third such composition. Prior to the première, Diaghilev had promised “a new thrill that will doubtless inspire heated discussion” and Stravinsky had written the work as a solemn pagan rite and hoped to present a “great insult to habit”. When first playing the piano version for Diaghilev, Stravinsky was asked how long the dissonant, ostinato chords would sound, to which Stravinsky replied “to the end, dear Serge, to the very end.” The newly opened theatre, designed by Auguste Perret, was as avant-garde in construction as the contemporary music, opera and dance that was to be presented inside. The geometrically strict and decoratively plain exterior of reinforced concrete mixed modern and classical architecture and made it the perfect venue for what Debussy described as “primitive music with all the modern conveniences.”

The atmosphere before the performance was lively; the 29th of May was unseasonably hot, reaching a height of 30c, and the halls and corridors of the theatre were packed with those who had bought into Diaghilev’s hype. The house was sold-out, largely encompassing subscribers for the whole season of Ballet Russe and there was a fifty-fifty split in the guest-list between the Parisian elite of diplomats, dignitaries and dilletantes, and the Modernist art scene. Patrons such as Daisy Fellowes, (née Countess Severine Phillipine Decazes de Glückberg), an elderly Countess de Pourtales, and the ambassador of the Austro-Hungarian empire represented the upper crust, and batting for the avant-garde were the likes of Jean Cousteau, Maurice Ravel and Edgard Varèse. Cousteau was quoted later as saying that a scandal was primed by the mix, with “a fashionable audience [in] low-cut dresses, tricked out in pearls, egret and ostrich feathers…side by side with tails and tulle, the sack suits, headbands, showy rags of that race of esthetes who acclaim, right or wrong, anything that is new because of their hatred of the boxes.”

Alfred Capus in Le Figaro reported that during the first bars of bassoon with discondant accompaniment in the closed-curtain introduction, there was prompt hissing and jeering. Incensed at a perceived misuse of the instrument, Camille Saint-Saëns exclaimed, “If that’s a bassoon, then I’m a baboon”, before storming out. The Countess de Pourales is recorded to have shouted “I am 60 years old and this is the first time anyone has dared to make fun of me”, to no one in particular. A back and forth between supporters and discontents followed, with the American music critic Carl van Vechten recalling “a battery of screams, countered by a foil of applause.” At the start of the Augurs of Spring section, the curtains opened and the ensuing polyrhythms, unresolved harmonies, rapid dynamic shifts, and familiar themes played in unfamiliar registers did not sit well with the patrons disinclined to experimental music. Furthermore, in an attempt to convey the agony of human sacrifice in a primitive society, choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky had his dancers land their leaps with flat feet which added echoing thuds to the music. At its worst, the din from the audience was so loud that it drowned out the music and Nijinsky resorted to shouting out counts to the dancers while standing on a chair in the wings.

According to Stravinsky, his friend Florent Schmitt shouted an insult to a group of elegant socialites, “taisez-vous, garces du seizieme!” and the various reactions and counter-reactions shared between the conservative and avant-garde sections pushed the battle onward. Diaghilev ordered the house lights to be flicked on and off in either an attempt to quell the uproar or, perhaps, sheer excitement at the press-baiting pandemonium he’d created. Stravinsky was horrified by the furore, leaving the auditorium to watch at the wings (it has been alleged in tears, but to claim so seems to kick a man when he’s down) saying later that he had “never been that angry”. At the intermission, the theatre proceeded to eject forty of the most troublesome, but it was not particularly successful in restoring full order.

Stravinsky and Nijinsky were devastated by the negative response and embarrassed by the spectacle, but Diaghilev took delight in the publicity of scandal, expressing complete satisfaction at a celebratory dinner after the show. Mainstream reactions in the press to “Le Massacre du Printemps” were not great, with Giacomo Puccini damning The Rite of Spring as “sheer cacophony” and Adolphe Boschot in L’Echo de Paris claiming (pejoratively, it should be noted) that the composer had “worked at bringing his music close to noise”. The performance immediately made waves internationally with The New York Times reporting under the headline: “Parisians hiss new ballet: Russian dancer’s latest offering, ‘The Consecration of Spring’, a failure”. However, there was strong praise from some publications and subsequent performances were far more successful.

“No doubt it will be understood one day that I sprang a surprise on Paris.” – Igor Stravinsky

Dissonant music wasn’t the sole cause of the chaos, with the angular and provocative dancing, anti-Russian sentiment, reactionary morality, and hype all part of a melting pot. However, the premiere was a key flashpoint in the debate over modernism, in which noise in music was a rapidly expanding form of expression. Arnold Schoenberg’s drive to “emancipate the dissonance” and expand the possibilities of musical expression lent dissonance a cultural cachet in the early 20th century. Schoenberg’s music was noteworthy for the absence of traditional keys or tonal centers and, although he faced a similar reaction to The Rite of Spring on occasion, his music and theories had lasting influence throughout the 20th century.

While composers such as Schoenberg and Stravinsky were experimenting with rhythm and harmony, the Futurist Italian Luigi Russolo, in his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises, was arguing that the public, accustomed to the sounds of industry and traffic, were hungry for “the infinite variety of noise-sounds” regardless of whether they knew it or not. For the Futurists, the explosion of mechanical noise in the 20th century evoked the activity, speed and progression that they celebrated in modern society. Russolo’s revolution was for music to no longer be a canonised system of notes, but rather understood as a structure of non-periodic complex sound. Russolo categorised these noise-sounds into six groups:

1. Roars, Thunderings, Explosions, Hissing roars, Bangs, Booms

2. Whistling, Hissing, Puffing

3. Whispers, Murmurs, Mumbling, Muttering, Gurgling

4. Noises obtained by beating on metals, woods, skins, stones, pottery, etc.

5. Voices of animals and people, Shouts, Screams, Shrieks, Wails, Hoots, Howls, Death rattles, Sobs

6. Screeching, Creaking, Rustling, Buzzing, Crackling,

Scraping

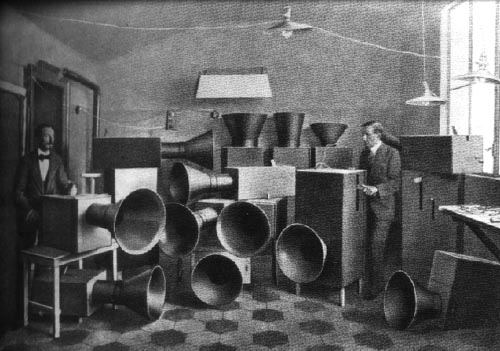

In order to produce these sounds, Russolo constructed 27 varieties of noise machine called intonarumori, each named after a different sound. The device was a crank-operated wooden parallelepiped box with a speaker at the front, the pitch being controlled by a lever on the top. The lever would modify the tension of a metal or gut string, wrapped round a wheel, that was attached to a drumhead inside the box.

Russolo introduced the public to these devices with a concert entitled Awakening of a City and Meeting of Automobiles and Airplanes in Milan in April of 1914, and, continuing the trend of violence in response to noisy spectacle, a riot ensued. Futurists in the audience responded to booing with fists, and eleven audience members ended up in hospital. In 1926, influenced by Russolo’s machine music, and anticipating Hanatarashi’s use of machines of industry, George Antheil produced Ballet Mécanique, which called for 3 airplane propellers to accompany the pianos, bells and siren in the orchestra. The reception to the piece was as mixed as that of the The Rite of Spring or Russolo’s Awakening, and the Paris première ended with – you guessed it – a riot in the streets. Despite the early negative reactions to these modernist experiments in noise, by 1940 The Rite of Spring was accompanying the extinction of cartoon dinosaurs in Disney’s Fantasia and the following decades would see avant-garde composers such as Harry Partch, John Cage and Karl Stockhausen produce music that would have presumably killed the Countess de Pourales on the spot. These experimental composers would eventually find their ideas pushed into pop music by the likes of Sonic Youth, who managed to straddle the seemingly incongruous worlds of MTV and the art music underground, with the benefit of an audience of noise-primed Gen X youth.

“We believed that music is nothing but organized noise. You can take anything—street sounds, us talking, whatever you want—and make it music by organizing it. That’s still our philosophy, to show people that this thing you call music is a lot broader than you think it is.” — Hank Shocklee of Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad, Keyboard Magazine, 1990

From the purposefully consonant compositions, within strict rules of tonality, of medieval religious music to the chaotic noise of Tokyo’s Merzbow or Detroit’s Wolf Eyes, dissonance has moved from something to be avoided to become an all-encompassing driving force. What was an imperceptibly gradual change before the 20th century has now become rapid. The relationship between an experimental composer and his noisy environment and the advances in music technology have led us to the point whereby people will pay for a MP3 of almost pure white noise and call it music. Cued by Willie Kizart using a damaged amplifier on the recording of the Kings of Rhythm track Rocket 88 and furthered by Dick Dale’s work with Fender, the electric guitar turned distortion and feedback into an art-form, driving music more towards timbre than harmony. Experiments with synthesisers, from Elisha Gray’s basic single note oscillator in 1876 to Hugh Le Caine’s Electronic Sackbut, engendered real-time, precision control of volume, pitch and timbre. Rather than Russolo’s acoustic noise generators, noise could now be artificially created in exact and varied ways. With the development of recorded music from tape to digital memory, sampling became a new form of replicating and altering environmental noise. Just as Russolo and Antheil would take from the sounds of the modern mechanical world, musique concrete would mimic the electronic age with the use of tape loops and purely electronic-produced sound. The digital revolution would lead to the hip-hop sampling of Public Enemy, which took the sounds of New York streets and media soundbites and reconfigured the noise into dense music, punctuated by sirens and drills, that articulated urban conflict.

There are many ways of conceptualising dissonance. The term consonance comes from the Latin consonare, meaning ‘sounding together’, and has become synonymous with particularly harmonious intervals in Western music. However, there is a psychological aspect to consonance and dissonance which is subjective and has changed throughout history. Psychologists would describe dissonance as a negative valence emotional response, meaning that it conjures feelings such as anger and fear; emotions that relate to suffering. In harmony, consonance and dissonance refer to specific qualities an interval can possess but, although consonance relates to mathematical constants, musical experiments outside the acceptable ranges of the time attuned the human ear gradually to more dissonant sounds. In the Middle Ages, the tritone musical interval (the interval between, for instance, F to the B above) was once prohibited by the Roman Catholic church due to its dissonant qualities and perceived ties to the Devil. Nowadays, however, this very interval is one of the main building blocks in jazz harmony, especially in the music of Duke Ellington and Art Tatum; music considered completely palatable to today’s ear.

Differentiation in ability to determine pitch, timbre, volume and time between tones could account for more or less appreciation of complex music. When two pitches are played together the mind appreciates the combination while also picking apart the unique pitches. More distortion or dissonant intervals will lead to added overtones and sum tones, creating very complex waveforms, which will force the listening brain to work harder to decipher it. These complex waveforms are what people would be hearing in music they consider to be difficult. The reason why some people react so poorly to modern classical music that delves into dissonance is that there are no easily discernible patterns. Philip Ball, in The Music Instinct, writes that “the brain is a pattern seeking organ, so it looks for patterns in music to make sense of what we hear.” The lack of predictability of tone sequences in the music of Stockhausen, for example, can confuse the brain, but the mind can learn to appreciate the complexity. We learn to appreciate this through listening to more complex music but, as the noise in our environment has increased, it is our adaptation that further enables us to enjoy what previously was rejected. The music mimics the noise in the environment and, in turn, the environment programs us to accept more noise as music.

Who are these loud and noisy people? They are like fishermen hawking fish.” – Buddha

How much has noise increased in the past few hundred years? Statistical comparison is a struggle, but noise appears to have been a concern for every society throughout history. The Buddhist Digha Nikaya, committed to writing in 29 BCE, records some contemporary noises of concern:

“Ananda, was neither by day nor night without the ten noises,—to wit, the noise of elephants, the noise of horses, the noise of chariots, the noise of drums, the noise of tabors, the noise of lutes, the noise of song, the noise of cymbals, the noise of gongs, and the tenth noise of people crying, ‘Eat ye, and drink!’”

Allowing for the unknown volume of an ancient Buddhist toast, the loudest sound on the list is that of the Asian elephant, trumpeting at a maximum of 90dB. The decibel level of the loudest sound in a city environment would increase as time went on, pacing more rapidly in the decades leading up to the 20th century. In an 1896 article entitled The Plague of City Noises, a clearly irate Dr. John H. Girdner called attention to the “injurious and exhaustive effects of city noises” from such sources as horse-drawn vehicles, bells and whistles, animals, persons learning to play musical instruments, peddlers, and that most infuriating member of late 19th century street-theatre, the organ grinder. What Dr. Girdner and the Buddha share is a concern for largely natural sounds of animal and human activity. However, the industrial and urban development of the 20th century altered the make-up of street noise and a poll of New Yorkers in 1929 issued an updated list of ten sounds to break a Buddhist samantha, with every one a product of a mechanisation.

The everyday noises of Girdner and the Buddhists pale in comparison to what the modern ear has to contend with, especially baring in mind the logarithmic nature of the decibel scale. Rule of thumb: the sound must increase in intensity by a factor of ten for the sound to be perceived as twice as loud. A car horn (120dB at 1 metre), a jet flyover at 1000 feet (103 dB), a power mower (96 dB), a food blender (88 dB), and a car driving at 65 mph (77 dB at 25ft) could conceivably occur simultaneously and for extended periods of time, albeit in a particularly poorly-situated home. Even the average lowest limit of urban ambient sound today is 40 dB; a constant hum that crosses the frequency spectrum.

“Natural sounds generate a sinusoidal wave, with rounded peaks, which is easy on the ears. Many mechanized sounds are square or sawtooth shaped or have jagged edges. If you see them on an oscilloscope, you’ll know why they’re unpleasant to listen to.” – Gordon Hempton

The increasingly urbanised and industrialised modern world has become a place of almost constant unnatural sound. The American acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton contends that in the whole of the United States there are just 12 places that could be considered naturally ‘silent’. By measuring average noise intervals at various locations over time, Hempton demonstrated that in the state of Washington there are just 3 places that are free from anthropogenic noise for longer than 15 minutes, compared to 21 places in 1994. In the UK, research by Sheffield Hallam University found that Sheffield City Centre was twice as loud in 2001 as it was in 1991. With this increase in the spread and intensity of noise there has followed a general adaptation and acceptance of noise, but accompanied by some very negative consequences.

The word noise is derived from the Latin nausea, meaning seasickness, and noise can have many physiological and psychological effects that are deeply unpleasant, even causing permanent harm. In addition to the obvious hearing damage that can occur from repeated exposure to loud sound, diverse research over several decades has uncovered a variety of problems related to noise exposure. Fatigue, irritability, insomnia, headaches, anxiety disorders, depression and an increased prevalence of stress diseases have all been shown to be possible negative consequences. A WHO report from 2011 estimated that Western Europeans lose over one million healthy life years annually from noise-related disability and disease. Noise could also be making us less kind to one another, as research into noise as an urban stressor has found that a noisy environment can increase anti-social behaviour.

A series of studies at Wright State University in the mid-seventies found that noise interferes with social cues from a person in need of help and reduces helping behaviour. Further study in 1979, at the University of Washington, into noise and social discrimination found that noise may cause people to distort and over-simplify complex social relationships. Key to these outcomes, both physiological and psychological, appears to be our primal response system. Studies of blood chemistry have shown that exposure to noise causes an increased production of epinephrine, a central component in the fight-or-flight response. The more ‘unpleasant’ a sound, the more the amygdala, which plays a role in processing fear, is activated and therefore the stronger the emotional response.

The only rational reactions to an environment that threatens are either to escape or to adapt. However, even if one can ignore it, there is no physiological habituation to noise; an auditory assault affects us even when not consciously registered. Furthermore, it appears that the adaptation to noise that modern life requires is leading to an increased fear of silence. In 1999, the BBC accountancy office was refurbished with noiseless air-conditioning, double- glazed windows, and silent computers.

The makeover was effective in abating noise, but the employees were uncomfortable. They complained that the silence was stressful, leaving them feeling lonely and paranoid that others were listening in on their phone calls. In response, upon consulting noise expert Yong Yan from the University of Greenwich, the BBC decided to buy a noise machine to combat what Yan calls Pin Drop Syndrome. This covered the silence by producing a continuous 20 dB murmur of unintelligible voices, with the occasional snippet of bottled laughter, and the accountants relaxed into their faux-hubbub soundtrack. In a world of noise, silence equals exposure. The noise can fill in spaces that separate, cover up the sounds that bring attention and can blend individuals into an amorphous group. Perhaps it was this comforting, masking relationship with noise that the BBC accountants were found to be craving when absent.

Our ears have an inbuilt hypersensitivity to sound that was invaluable in the days when humans were hunter and hunted. We can hear a pin drop in a quiet room because our auditory system enhances the volume of a sound to several hundred times louder than the source volume before the brain itself registers the sound. While humans have transformed their relationship to environment and the conscious perception of noise, the brain and auditory system are still somewhat stuck in the fight-or-flight world of pre-civilisation. We tune out the noise in our daily lives but the physical and psychological forces are still present, pushing up blood pressure and promoting the release of stress hormones behind-the-scenes, even when we aren’t consciously aware of the sound.

“Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating” – John Cage, The Future of Music: Credo, 1961

Today there is no firm basis for a distinction between music and noise. With the abandonment of traditional, harmonic definitions of consonance and dissonance, the distinction is entirely subjective and particular to context. There is no such thing any more as the ‘non-musical sound’ that John Cage wanted to highlight in his compositions; everything is fair game. We are born into noisy environments and the necessary adaptation means that the normative level of acceptable noise has been rising exponentially with each generation. But with musicians of today using white noise, the entire range of audible sound-wave frequencies heard simultaneously, where is there left to go?

The Austrian anthropologist Michael Haberlandt claimed that the more noise a culture could bear, the more ‘‘barbarian’’ it was. Hanatarashi’s bulldozer performance was nothing if not proudly barbarian, but the violent expression was peacefully received – unlike the riots that followed the performances of earlier noise music. Noise has found its audience and the Noizu crowd at Tokyo’s Super Loft were purposefully escaping any sense of tranquility, seeking out that dangerous thrill that the body provides when the fight-or-flight response goes haywire. Like skydivers and train- surfers they were after the exhilaration that comes from hacking the body’s primordial response mechanisms. They were all freaking out together, each body screaming to run but with safety in numbers and the perversely comforting wash of noise connecting and concealing everyone. The enjoyment of the performance came from the transgressive destruction on not just the venue but the audience themselves. They were pushing at the biological limits of their minds and bodies, going against the grain like the boundary pushing experimental music, in order to feel a rush. In earlier decades, or centuries, that rush could have been achieved with less. The charge of a herd of elephants or the clattering and cheering of a horse race might have once been at the upper limit of common noise, but with the constant, and constantly increasing, cacophony of noise in our environment today, the level of acceptable noise has been dragged further up the decibel scale and further out from consonance. The result of this trend is that the noise music listener will always be like a heavy drug user who requires an ever increasing fix. The Hanatarashi fans amongst us are bathing in extreme noise to induce the fight-or-flight response; musical adrenaline junkies looking for a high that the body and mind will continue to adapt to over time. Only, unlike drug use, everyone is taking noise everyday, whether we like it or not, and we have to choose to either embrace it or escape it.

But where to escape to, when silence is disappearing? Perhaps noise music highlights how people are too accepting of the damage and social alienation that the daily exposure to noise is producing. Are we all barbarians for living with noise that would have driven our forbears crazy? Noise is now presented by health authorities and scientific studies as a pollutant but, unlike with oil spills and insecticides, some people inure themselves to this pollutant through choice. By choosing to embrace the constant noise of modern life, with all of its negative effects, they are like the BBC accountants, a symbol of the slow death of silence. If a solution isn’t found, there might come a point where the silence on Earth is found through noise-cancelling headphones rather than a trip out of the city, and natural silence will have truly vanished. And what will the music of that time sound like? The Rite of Spring sounded like noise, even Beethoven sounded like noise to the ear of the day, so in a few hundred years time will we be looking back on Hanatarashi with a feeling of quaint nostalgia as we wonder how anyone could have considered such classics as Boat People Hate Fuck or White Anal Generator to be noise?

About Kieran Gosney

Kieran is an Edinburgh-based film editor and writer. He currently writes about editing and reviews films for The 405.