You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In her corner office, Sister Modesta Cuma opens a notebook and considers a list of boys and girls under her care. She knows the story behind each name.

Lucera, 10. Mentally disabled. Lives in her own world. Here five years.

As director of Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello, a Catholic orphanage for HIV-positive children, Sister Modesta is responsible for forty-five youngsters ranging in age from a few days to fifteen years old. The orphanage stands beside a dirt and stone road that wends through a dense jungle of leafy trees in the village of Sumpango, about fifty miles outside Guatemala City, Guatemala, and near the town of Antigua, once Guatemala’s capital and now a popular tourist destination. Nuns with the order of Small Apostles of Redemption care for the children behind high walls that shut off the trees and the road and the noise of traffic converging on Antigua. Within the compound an orderly world of classrooms, dormitories, a chapel, and a playground, replete with basketball court, swing sets and slides provide an alternative universe of calm and safety in which nuns occupy the roles of parent, teacher and protector.

Fernando, 8. Both of his parents are addicts. He has absorbed all of their problems. When he started walking, he would throw himself against walls. He couldn’t be left alone. His parents are now dead. They lived in Zone 18, one of the worst neighborhoods in Guatemala. Fernando’s uncle was shot. He’s hiding somewhere. Drugs, violence, gangs. It’s in his blood.

Sometimes, when a mother visits the orphanage, her son or daughter does not recognize her. The child cries and the mother gets angry. She doesn’t understand that the nuns have replaced her.

Gustavo Ramirez, 11. He has no family other than an aunt but she rarely visits. Just recently, however, she took him for a few days.

All the children were born out of tragedy. More often than not, their mothers became pregnant after having sex with an HIV-infected man. Some of them worked as prostitutes. Others were raped. Still others injected drugs with dirty needles and continued using after they were pregnant. Then doctors and police get involved. Then the courts refer the children to Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello.

Despite having the HIV virus, the children impress visitors with their joy and laughter so much so that a few visitors leave refusing to believe the children have any health issues at all. However, Sister Modesta knows better. A three-year-old died in 2014. He was so sick when he arrived that no amount of medication could save him. The children of Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello live with the threat of death every day.

Ignacio Bachub, 14. Came to the orphanage when he was eight years old. He has an uncle in the U.S. but no close relatives in Guatemala.

Sister Modesta could never have anticipated that her life would lead here when, as a twelve-year-old, she told the nuns in her hometown of Santa Maria de Jesus, Guatemala, that she wanted to join the church. She had been impressed by their stories of traveling to Africa and other faraway countries. Many of her teachers had degrees in medicine, economics and other professions. Their knowledge impressed her. Unlike her mother, they could read.

The nuns told her she would not understand the call to Christ until she turned eighteen. Sister Modesta, however, was undeterred. How much does a habit cost? she demanded. It’s expensive, they told her. Too much for a twelve-year-old. Still she persisted. Because of her commitment, or stubborn persistence – she can’t be sure which, although she leans toward the latter – the nuns relented and she began her studies to live a religious life in 1982 when she was seventeen. As a novice, Sister Modesta worked in Colombia and later in El Salvador. She also earned a nursing degree. In 2015, she was assigned to Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello.

Abimael Chilisna, 11. He is allowed overnight visits with his family. However, they forget to give him his medicine or feed him a proper diet. They work all the time and leave him alone. When they return him to the orphanage, Abimael won’t take his medicine. His family didn’t make him take it, so why should he take it now? he asks. The courts have been informed of the problem. The next time his family asks for him, the courts will decide whether he goes or not.

Every year, Sister Modesta knows, a child will leave Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello. Their families take them back. The courts transfer them to another facility. They turn eighteen and are no longer considered children. The sisters hope God will help them. They pray that the children get through the difficulties of entering into a world far different from the one they’ve known here.

Heidy Herrera. There are some things about her life she does not know. She does not remember her mother and that is probably a blessing. When her mother learned Heidy was HIV- positive, she locked her in a cage inside the house. Her older siblings took her to her grandmother’s house and then called the police on their own mother. The courts placed her here. Her grandmother and uncle visit but not often.

Sister Modesta closes her notebook, digs into the pockets of her vest to warm her hands, and sighs. Discharges can end badly. Recently a girl left and began dating a bad boy and they eloped. Her grades went down. She stopped attending school and taking her medicine. Eighteen years old. Gone, never heard from again. Sister Modesta still prays for her.

*

Heidy Herrera sits alone on steps that lead into the playground and watches a handful of children shooting hoops. Their shadows climb walls, shrinking and expanding as they run. Heidy pulls a sweater around her shoulders against the evening damp air and the far-off reverberations of thunder. She does not know her age. The nuns have told her she is fifteen and she accepts that but because she did not know herself she doesn’t know how to feel about it. She knows she’s getting older and that she can’t live at the orphanage forever. She does not remember when she came here, or who brought her. She got really sick while she lived with her grandmother, or so she’s been told. Her grandmother didn’t understand the problem. Then the police took her to a hospital where she received tests and then she ended up here. Her earliest memories belong here.

Heidy understands HIV can’t be cured but with the right treatment she can live a normal life. Without medicine, she understands HIV would develop into AIDS. She feels at ease, tranquil about her diagnosis. She can live with it. She has for a long time. She is the oldest child in the orphanage. She knows the time for leaving nears. Thoughts about her future preoccupy her. Her older sisters have agreed to take her in but they live far from Sumpango. The nuns are her family. Will she see them again? She does not think so and the thought saddens her and her eyes well with tears.

She remembers an older boy who moved out. He was eighteen. He was friends with everybody. All the children were sad to see him go. When he visits he plays with everybody. He lives far away and doesn’t come often. When he goes, it feels like the first time he left.

Nuns also leave. At the end of each year one or two get new assignments. Sister Sandra Flores left in 2014. She took care of all the kids and was really affectionate and playful. Every now and then she drops by and Heidy embraces and holds onto her until she gently pulls her arms away. It seems to Heidy it’s always her favorite people who go. She gets nervous at the end of each year wondering who will tell her goodbye.

*

Sister Maria Chub stops by the clinic to look in on two infants: Kendel, eighteen months old, has a heart condition and doesn’t gain weight. Selvin, eight months old, came to the orphanage because his HIV-positive mother refused to seek medical treatment for herself and him. She fed Selvin water and nothing else. He was horribly malnourished when he arrived.

Sister Maria sees love in the faces of the mothers who visit their babies but in most cases they continue living the life that got them sick. Sister Maria doesn’t judge. These mothers must eat. They are poor and care for themselves in any way they can. If you don’t feed the body, you can’t feed the spirit, she reminds herself.

Still, she gets angry. One year, the mother of an infant boy Sister Maria had grown very fond of appealed the court order that had removed him to the orphanage. The mother got the boy back but did not give him his HIV medicine. The boy got sick and the court returned him to the orphanage. His mother appealed again and won. This time she gave him his medicine but it was no longer effective because he had gone without it for so long. Doctors said he needed stronger drugs unavailable in Guatemala. The boy died. Just five months old.

The boy’s death broke Sister Maria’s heart. Her anger at the mother knew no limits even with prayer. The mother had an opportunity to help her son but chose not to. The boy looked normal but he was sick inside. Had he been allowed to stay at the orphanage he would have received his medication. He was family. He was so cheerful despite being sick. He really liked it here but his mother wanted him. He was so small. He cried when he left. All Sister Maria can do is pray for his soul now. She weeps with fury and frustration and asks God’s forgiveness of the boy’s mother and herself.

*

Twenty-three-year-old Floridalma Perez sits in a park about a mile from Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello, where she once lived and now volunteers. She watches her three-year-old son, Alex, play on a slide. Men and women walk in and out of a convenience store nearby. Discarded bags of chips blow in the wind and Alex picks up one and Floridalma tells him to drop it. The wind carries it away beneath a gray sky warning of rain.

—Be careful on the slide, she cautions him.

When Floridalma was five years old, her mother died. Her father sexually abused her for many years and infected her with HIV. She told her older siblings about the abuse but no one believed her.

When she started getting sick, her father left her at a hospital. The hospital staff contacted the police and she was referred to the orphanage in 2006. She was thirteen. She never saw her father again until she turned twenty-one when he asked for her forgiveness.

—No, you have destroyed my life, she told him.

At Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello no one told her she was HIV-positive until she turned seventeen. Until then, she took medicine but never understood its purpose. Perhaps the nuns thought she wouldn’t understand.

At eighteen, she left to live with an uncle in San Marcos, Guatemala, where she was born. However, he didn’t want her to stay with him so she rented a room and worked as a maid in a wealthy man’s house. He raped her and she became pregnant with Alex. When she told him, he said, Go away. She doesn’t know if she infected him with HIV. She didn’t know then that HIV was transmittable through sex. The sisters had never discussed sex with her.

When she was seven months pregnant, Floridalma called the orphanage and told the nuns what had happened. They invited her to return and put her on medication. She stayed at the orphanage until Alex was born free of HIV. Thank God he is healthy, she often tells herself, thank God. She rents a room near the park now. The nuns continue to give her food and medication.

Floridalma wonders, Why is there so much suffering? She worries for the children when they leave Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello and face a world so different from the one they’ve known. She says, Hi, how are you? and the children smile a greeting in return. She doesn’t have a relationship with any of them or with anyone else for that matter other than her son. She wants him to stay healthy. She wants him to have the childhood she didn’t.

*

Daily Schedule:

5:30 a.m. wake up, administer medication

7:00 a.m. breakfast

8:30 a.m.–2:45 p.m. school

1:00 p.m. lunch

1:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m. homework, chores

4:00 p.m.–5:00 p.m. recess

5 p.m.–6 p.m. church

6 :00 p.m. dinner

8:00 p.m. bedtime

*

Sister Aleja Ocox paces the playground as she presides over recess. She took her vows in 2001 at the age of nineteen. She can’t say why exactly other than she attended parochial school and, besides her parents, knew only nuns as a child. As a young woman, her options were limited: join the church or get married. She knew no boy she wanted to marry so she decided to enter the religious life.

On this evening, she watches two boys chasing one another in a game of tag. They both have kidney problems as a result of HIV. One of them, eight-year-old Fernando, has lived here since he was a baby. He does not remember his drug-addicted mother. He puzzles Sister Aleja. He steals from the other children. Why is he like this? Perhaps because his mother was a drug addict and Fernando was born with crack cocaine in his blood. He sees a psychologist once a week. He can turn violent. He gets very aggressive and then calms down. Sister Aleja doesn’t know what to think of him.

Sister Aleja worked at the orphanage in 2006, was transferred to another orphanage and then returned in 2014. When she was here the first time, the orphanage didn’t have a clinic. If a child got sick, they had to be driven to Roosevelt Hospital, the public hospital in Guatemala City, more than an hour a way. The clinic has been a big help. Now, if a child falls or gets hurt in some minor way, they have a place to go within the orphanage. Poor things. They panic so if they bruise themselves. Sometimes even Sister Aleja panics. The slightest thing, even a sneeze, makes her worry they might get sick and die.

Sister Aleja especially keeps an eye on the little ones. She reminds them to take their medicine before they go to bed. Don’t catch cold, she warns them, don’t get wet. When the colder weather comes, wear a sweater. She worries all the time. Please God, let them stay healthy.

About once a week, Sister Aleja drives a van full of boys and girls from the orphanage to Roosevelt Hospital for routine checkups. She awakens the children at four in the morning so they can make their seven o’clock appointment. She maneuvers through the congested traffic of the capital with the impatience of a seasoned commuter. The gray-stone hospital rises above a parking lot filled with beggars and fruit vendors. Sister Aleja parks and hurries the children to the front doors, passes a security guard, and follows a hall that takes her to a row of examination rooms. She registers the children with a receptionist and then herds them together as she finds chairs for them all. They wait until Sister Aleja hears her name called. Standing, she takes the children to a bare room with charts of the human body tacked on the wall. A nurse seated behind a desk beckons each child forward.

Angelica, 12: Pointing to a spot on her left arm, she tells the nurse she knows where her good vein is to draw blood. Steady, the nurse tells her, so I hit the vein the first time. The last time I didn’t need lab work, but today it’s my turn, Angelica reminds her. The nurse nods as she inserts the needle. When she finishes, she asks Angelica to stand on a scale. She is still underweight, the nurse tells Sister Aleja, but she has always been a little underweight. Her cholesterol was high the last time we ran blood. Is she eating oatmeal to lower it? Yes, but she doesn’t like it, Sister Aleja says.

Nelson, 9: The nurse measures his waist, biceps and arm length and checks his weight. He watches her as she adjusts the scale. Look, up, look straight ahead, the nurse tells him. He gained two pounds since his last visit and grew 1.2 centimeters, she comments. How have you been behaving? she asks him. You have a look like you’ve been misbehaving. He giggles. She considers his chart. Viral load untraceable, good. White blood cells normal. Kidney, liver very well. Have you been sick? No. You’re so quiet, guapo. Why don’t you say anything? He smiles.

Josue, 9: He gained two pounds since his last checkup and now weighs fifty-five pounds. He grew one centimeter. Has he been ill? the nurse asks. No, Sister Aleja says. He’s gained weight, the nurse continues, that’s good. White blood cells normal, but his fatty acids are up. Give him Omega 3.

After the children have been examined, the older ones who know what it means to be HIV-positive meet with a counselor. The counselor tells them they’ll be OK if they take their medicine. You have limitations but do the best you can with the life you have. Give an example of how you can respect yourself. Do you brush your teeth, shower, eat every day? Yes, a boy answers. Those are things we can do to show our bodies respect and love, the counselor says. Every day you should do something that shows you love yourself. Every day, the boys says, I drink water. Good. What else? I take my medicine. Yes, the counselor agrees, that’s also good. If you take your medicine every day, you’ll be OK. From your blood work, I can see your medicine is working. How does the medicine help you? It doesn’t let the virus hurt me, the boy replies. What’s the difference between contracting and transmitting? If I use a needle, he says, I’ll contract it. If someone sneezes will you contract? the counselor asks. No, the boy replies. If you share a cup of water? No. What about sexual relations? Yes, the boys says, unless I use a condom. Very good, the counselor says.

*

Dreams.

Gustavo Ramirez: I dream about my family. I dream about going home and spending Christmas with them. In my dream I see my family. Everyone is happy.

Abimael Chilisna: I dream of being with my family. They come and pick me up and take me to swimming pools. I feel sad about leaving. I’ll leave my friends. All my friends are here but I’m a little happy because I’ll be with my family.

Floridalma Perez: I have dreams for my son. I want him to have what I didn’t. I know this will be difficult because I still don’t have what I want him to have, a home and safety. I don’t have dreams for myself. I have nightmares. One positive dream out every ten nightmares. The good dreams are of a life that is not difficult but once I wake up everything falls away. My nightmares are all related to accidents, car crashes or in a bus. I’m afraid of something happening to my son and me.

Heidy Herrera: I dream of living a normal life without medicine.

*

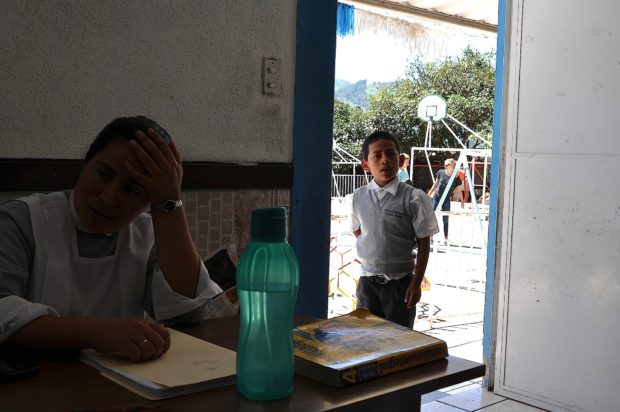

Social studies class. Third- and fourth-graders.

Today’s lesson: de la violencia a la paz. Violence versus peace.

—Take out your notebooks, Sister Modesta tells the class of eight- and nine-year-olds. The boys and girls shift in their chairs, rummaging through shoulder packs, rocking the small desks on the concrete floor and the damp air made damper from a lingering morning fog clings to the room and the children rub goosebumps from their arms.

—Give me some examples of violence, Sister Modesta tells the class.

—If one boy punches another boy.

—If one boy says I’m better than you that is violence.

—If siblings fight for the love of the mother.

—One at a time, Sister Modesta says.

—When they drink, people become violent.

—Brothers and sisters fight for the love of their mother.

Sister Modesta writes their comments on the board. She has chosen this topic because she knows some of the mothers of these children were raped. The children themselves have experienced physical abuse and social exclusion. She wants them to see this behavior as wrong and not repeat it themselves when they become adults.

*

After class, Ignacio Bachub approaches Sister Modesta.

—I’d like to be a chef, he tells her.

—Whatever makes you happy, she encourages.

Maybe a chef working in one of Antigua’s many restaurants would come and talk to him, she thinks. Perhaps even apprentice him. Why not? These children should be loved as much as anyone and have the same opportunities. They complain that they’re not like other boys and girls. Don’t feel dejected, she tells them. You will outgrow these disappointments, but she doesn’t know if she believes that. With each child she feels the vulnerability of her ignorance of God’s will. She prays for their health and welfare and then waits as uncertain as the children under her care for what the future holds.

About J. Malcolm Garcia

J. Malcolm Garcia is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.

- More Posts(5)