You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

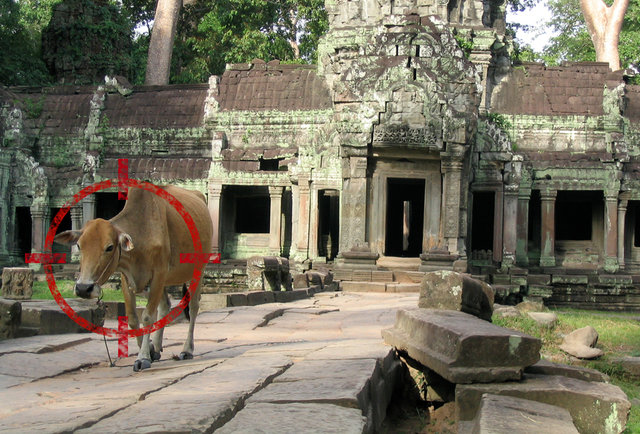

Go shopping“So, would you like to go and shoot a cow with a rocket launcher?”

As questions go, it is one of the more unusual. In actuality, it is not even factually accurate. The rocket launcher is, in reality, a rocket propelled grenade and the cow is sometimes a cow, other times a goat, depending upon the season.

Of course, none of this really matters. I can count the number of times I have wanted to blow up livestock on exactly zero fingers. I have not come to Cambodia to make farm animals explode and, even if I had, the timing of the pitch could not be more misplaced.

The offer is being made by the smiling driver of our tuk-tuk who beams at us in a way that suggests he has already guessed the answer, but enjoys asking the question anyway.

In Cambodia, everyone smiles at you. It has become a curious, disconcerting, national pastime. People smile at you in the morning as you exit the hotel and they smile at you as you pass them on the dusty side-streets. Grubby street children will smile at you as they try to sell you trinkets by the roadside and they will smile at you when you politely decline. Shop owners will smile at you when you buy things and they will smile at you when you don’t.

As a westerner, more used to the grim salutations of bored, safe people, living comfortable, safe lives, this relentless, sunny cheeriness is unsettling in a way that can be difficult to place.

Despite this almost ever present jollity, there are places where the smiling stops so suddenly as to be jarring. These are the places where redundant signs instruct you absolutely never to smile under any circumstance. The signs in these places are as superfluous as the tuk-tuk driver’s question, because nobody would ever willingly smile in these places, just as even the most bloodthirsty bovine hater would never wish to blow up a cow, or anything else, for that matter, after visiting them.

These are the places we have come to see.

It is early in the afternoon when we first stroll through the gates into the vast grassy compound of Choeung Ek. Here, tourists, mostly westerners, migrate lazily around a large white building that resides somewhere in the hazy middle distance. Most of them are shaking their heads at questions they have only just begun to form and the majority of the head shakers are peeling away from a tall white building that rises up from the earth like the bleached arm of a lonely skeleton.

At first glance, the building appears to be a typically well-kept, Buddhist stupa. It is only as we draw closer that the glass panels that line its central structure begin to slowly reveal their contents to the naked eye.

The skulls are neatly arranged: Layered and tiered like the decoration of a macabre wedding cake. All of them are missing the lower jaws. Most are cracked at the base from the force of the weapon that changed them from breathing, living, happy people into a grotesque record of the genocide that took place here. The sun blasted skulls rise up in piles, uncountable and unfathomable. They have been sorted to differentiate men from women, pensioners from children, but this perfunctory labelling is the only headstone that they will ever now receive.

Outside the building a sign reminds us to please “not walk through the mass grave” and another reminds us, again, not to smile. Nobody has come here to smile. Most have simply come here to try and understand.

It is an easy thing for people of my generation to look back at the Holocaust as a horror from a world they never knew. It is, perhaps, just as easy, for people who have never travelled here, to regard Pol Pot as some distant dictator in a land they will never really get to know or see. To visit Cambodia’s killing fields is to properly understand that this is not some distant relic of a mad world from an age long departed. All of this happened in my own lifetime; while I was growing up and going to primary school, the Khmer Rouge were turning Cambodian schools into prisons and filling the surrounding fields with the bodies of children my age.

We pass a large, ancient tree. It has been dressed brightly with the sort of day-glow wristbands that small, Cambodian street children will sell you for a dollar each.

A sign informs us that this was the infamous “killing tree” where children, torn out of their mother’s arms were dashed, head first against the trunk before being tossed, skulls split but still alive into the mass graves that contained the bodies of their executed parents. Beside the tree, a glass box stands, containing, among other things, a tiny pair of blue shorts.

‘When the rain comes,’ explains the guide, ‘old things rise to the surface. There is a lot that is still buried. A lot we have still to find.’

A tiny human jawbone sits on top of the box.

If the killing fields are preserved in such a way as to try and ensure that we never forget what took place here, then it is the next stop on the tour that exists as a reminder of just how easily all of this could happen again.

Having spent the past few years teaching in Public schools across Asia, the familiar structure of Tuol Svay Pray High School is unnervingly familiar to me. The empty outer courtyard and classroom layout is, more or less, identical in structure to the public schools that can be found across South East Asia to this day.

In 1971, the Khmer Rouge seized this school and transformed it from a place of education and learning into the torture, interrogation and execution factory, S-21.

Wandering, lazily around the abandoned classrooms turned torture cells, there are more signs bolted to the walls. The signs display laughing faces with a red x marked through the mouth.

The message is the same all over:

Do not laugh, here. Do not smile.

I wonder again, who the message is directed at. The horror of this building, now preserved as a permanent museum to the evil that took place here, is in its silence. It is carried less by the grim records that can be perused by visitors, but by the absence of children from their natural environment. It is S-21’s existence, not as a former torture camp, but as the ghost of a school that shakes a teacher the most.

Riding back to our hotel at the other end of the city, the signs advising people not to smile begin to disappear and, gradually the familiar Cambodian warmth returns on the dusty side streets. A motorcycle strapped with at least fifty bemused looking live chickens blares past us and I smile and shake my head at my girlfriend in a sign that we are returning to what passes for South-East Asian normality.

Still, as we ride, my mind can’t rid itself of all those signs and I wonder what sort of pathologically unbalanced person must have wandered into the killing fields or the prison camp of S-21 and laughed at what he saw there. What kind of a maniac, I wonder, needs a sign to tell him not to smile at all of that horror and atrocity? I assure myself that this person, in all likelihood, does not exist and that the signs are, almost surely, unnecessary. As we bounce along the dirt roads, I think about how all of this genocide happened within my lifetime and ruminate over whether it could ever happen again.

By the time we turn back onto the highway, I have almost convinced myself that Pol Pot was an aberration, a psychotic and an evolutionary mistake that will never be repeated. It is then that I am asked the question about whether, having spent the day taking in all of the worst of humanity, I would like to finish it off by blowing up a cow with a rocket launcher.

I shake my head and wonder how many times the tuk-tuk driver must have asked that question to tourists and how often he must have received a positive response in order to keep on asking it.

I imagine another man sitting in the back of the tuk-tuk, maybe weeks or months from now. I imagine him nodding calmly at the driver’s suggestion.

The man is smiling.

He is always smiling.

I hold my girlfriend’s hand tightly as we ride back to the hotel.

I am suddenly, terribly afraid for the future.

About Michael Teasdale

Michael Teasdale is an English writer, originally from Newcastle upon Tyne. He has enjoyed spells living in Sweden, Vietnam and China and currently lives in Ko Samui where he collects cats. He has previously written for Novel Magazine in the UK and blogs and writes at shoeboxofstories.com