You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The doctor’s house is a mile from the play-park. I don’t ask why you are driving me there and not to hospital, or how you know where a doctor lives, or why you did your make-up in the rear-view mirror. You say to keep my ankle raised on the back seat as the Morris stammers along the lanes and I cry out with each gear change.

I wait in the car while you knock on the front door, my foot da-dum da-dum-ing as if it has its own heart. The doctor’s wife helps you to take my weight, says they are only just back from church, emphasising the word before leaving the room. The study is cool and smells of leather and stationery, but it’s the display cases of stuffed creatures lining two of the walls that make me forget my ankle: fox, badger, weasel, an animal I don’t recognise, glassed eyes lancing into us.

The doctor enters yet the only noise is the tock-tock of the tall clock in the corner. He sits at his desk, back to us, rolls his shirt sleeves up. Finally, you fill the silence with Please – which I think is for me but isn’t – and when you say it again it sounds as if you might cry. He ignores you and attends to my leg, his hand, although huge as it holds my foot, as soft as yours. You fetch the tissue from beneath your sleeve, dab your face, explain how I am always doing stuff like this. Again, there is no response and you scrunch up the edges of your dress, look around the room. You see the animals for the first time since we arrived and for a moment I think you’ll pick up something heavy and smash the glass, freeing them all.

The doctor lowers my ankle and calls to his wife. You do as the woman asks and hold ice wrapped in a towel against my leg while he fetches a bandage from a drawer. And then in silence the two of them attach it, the doctor winding the gauze as she presses lightly on one end with a finger, then holds the other as he pins it. At no point do they meet your eyes. And so the creatures watch me watching you watching the doctor and his wife.

Years later the doctor will take his life in the field below the house and you will wear black for a week.

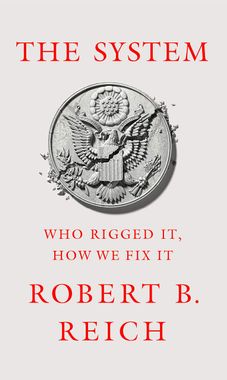

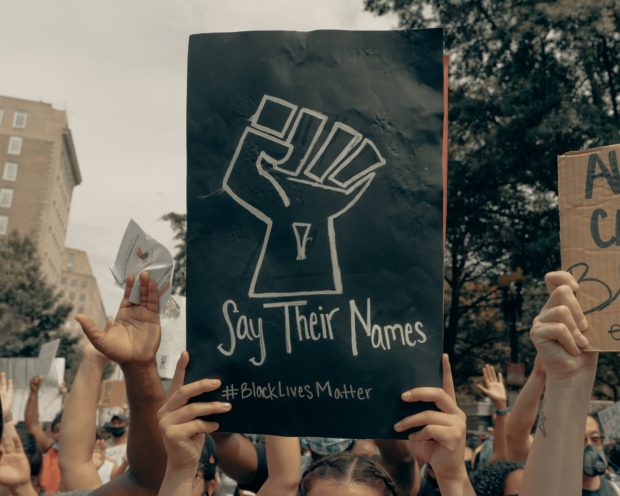

I had a great uncle who worked for a big lumber company, and got sick from the poisonous chemicals he sprayed to maintain the grounds. The nerves in his hands died to the extent that he’d drop things without knowing it. Or he’d get pulled over for driving too slow on the highway and when the cop asked him where he was going he couldn’t remember. He died in his late fifties, from brain cancer, and I remember him sobbing a lot in the back bedroom. His wife had to put locks on all the windows so he wouldn’t wander off in the night. I don’t have much else to say about him. I just think he should be remembered. I think people should know what those with money do to those without it. We couldn’t even bury him. It was too expensive. We cremated him and drove him up to the Red River, where he liked to ride four-wheelers in the spring. It was spring then too. The birds had come back. I remember we all took a handful, and lowered our hands into the water, and let go.

The family is off-kilter, their footsteps out of sync. The rope bridge shudders above the stream, a trickle of chocolate milk coiling between the camp and the Savannah.

That first night, a chorus of whooping hyenas swells beyond their tent and the porcelain-skinned child whimpers in his bed. His father curves over him, soothing him to sleep. Outside, a Maasai stands guard. Wrapped in a red checked shuka, his legs are spindly and bare.

The boy’s mother lies alone, remembering the service station en route to the airport; remembering the heat, the whine of cars, the molten blood throbbing at her temples.

“It’s safe,” her husband had said, without curling his body around hers. “Just don’t walk around at night.” His sigh was scalding.

The morning of the game drive, the boy skulks over the dappled grass towards the breakfast table. She wonders if the fear lurking in him is really hers. But by late afternoon, he is laughing as the Jeep bounces across the plains, his hair streaming golden in the setting sun. The bleached grass smells of childhood summers. Venus hovers on the horizon.

Returning to camp, a tyre bursts and they come to a halt. The night sky compresses the vehicle, slinking in through the open windows. They will have to get out and walk.

The guide leads them, armed only with his spear. She shadows his willowy figure, feeling ridged tracks underfoot, sensing shapes scurrying nearby. Cold drapes her shoulders, her skull is leaden, her limbs as if hobbled, but the boy appears taller, striding ahead.

A campfire wavers up ahead and from the dark, her husband’s arm envelopes her. Together, they cross the bridge spanning the strand of dusky water. Swaying. His hand is braided with hers, a floating path unravelling before them.

The children had washed up on the ring-shaped island. It was a pretty island, which one of the kids called ‘blue’, probably because he confused ‘blue’ and ‘green’. They grew hungry, having been accustomed to having their pablum carried by spoon to their gullets for them at regular intervals. They made do for a spell eating the tough, fibrous plants of the island’s western slope, though they bitched and moaned about it. A buncha weeks later they ventured to the eastern slope of the island and came upon a swath of sweet and tender-soft plant, new to them, which satiated their desires and propitiously served to solve the problem of how to fuel their return to the west now that they were east. Soon they were wearing a path back and forth from the one side of the island to the other to consume the plant in great numbers. They found when they returned to the west that they had a great need to defecate. The children felt pleased, if a little discontent with their contentedness, which is normal, something even a dumb kid knows. Weeks passed and the island began to fill with their feces; at the same time, the sweet eastern plant went from grazed to overgrazed. The children squabbled anew and gnawed, butts aloft and teeth at dirt level, at the remaining exposed stems of the eastern plant. They discovered they could no longer tolerate the fibrous western plants and came back to sit in the denuded eastern side and cried and cried among the remaining barren stalks, mixing tears with feces, until they expired.

And no one ever knew.

On birthdays but sometimes not, Ruth lived to fan out the jumbos with her thumb. The dirty work, of course, came first. Her fingers stiffened under the faucet as she extracted the dark, shiny string from the inner and outer curl. Her mother once taught her how to use cold running water to dislodge the grit, purge traces of the past.

Ruth had since developed a trick of her own, but only after the shrimp had been poached and chilled: a 3 to 1 ratio of ketchup to horseradish, lemon to parsley, and plate to mouth, her own mouth. For every three of the treats she spread out for guests, one went bang into the cakehole. All in the name of quality control, and anyway, it was the chef’s goddamn right.

Not that her daughter, out on the sofa, would care. She was the one who used to sneak in a few extras, even get swatted away, but since leaving home she had turned her back on shrimp. This from the same child who begged to inspect them for any slivers of shell the faraway laborers might have missed. Her more recent technique, sharpened with every visit, involved a grating Are you familiar with? right before the rant. The landmark study this. The cockroach of the ocean that.

Ruth was rinsing the last few when her daughter shuffled in to refill her boyfriend’s drink. As she pawed around in the freezer for ice, she asked if her mother knew that deveining actually described the removal of the garbage-impacted digestive tract.

Uncanny, Ruth thought, spotting a tangle of intestines – right there! – in the drain.

And was her mother familiar with the fact that the Bible wasn’t such a fan, to which Ruth muttered Amen! under the hiss of the tap.

But what Ruth wanted to know was why her daughter was so hell-bent on spoiling the cuteness of shrimp. They had every right to paddle along in oily, beaded waters – shimmy through someone else’s trash.

Her daughter leaned against the counter and waited. Ruth bladed her hand on the cutting board and pushed. The slack, fleshy clump blanched as it hit the surface, breaking apart in the churn. She would just have enough time to empty the sink strainer before yanking the shrimp from the heat.

Once, twice, she slammed the strainer on the trash can. Again, harder – the saucepan shuddered and spit. The knot of shrimp guts clung to the steel, and soon it would be too late. The water would seethe and foam, scorch the dead and all the witnesses, but she banged, kept banging, and willed the dark, shiny string to let go.

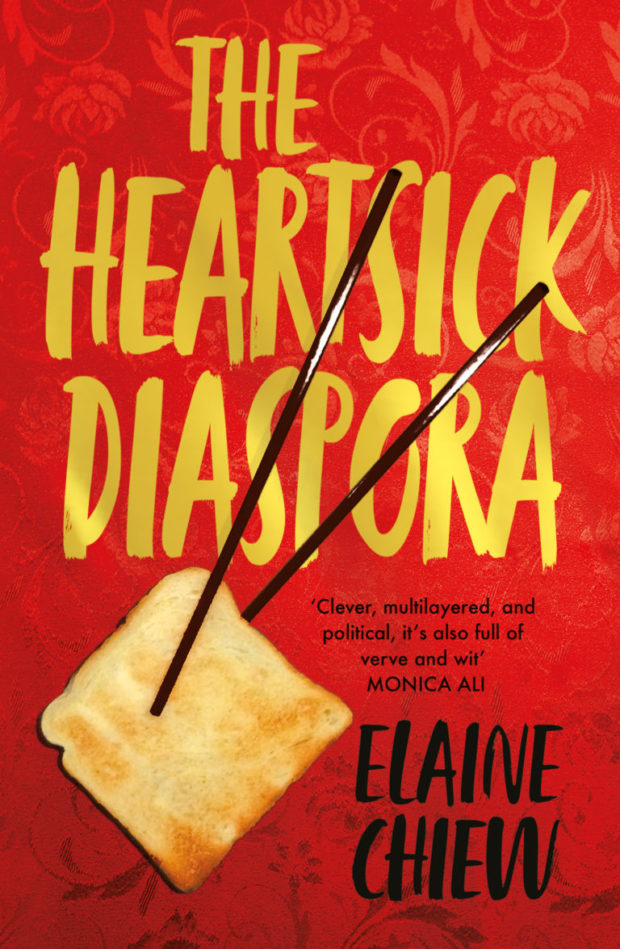

In the murky world where shadows blend into the even darker shades of espionage and international intrigue, David Bickford, with a past woven deeply into the fabric of British intelligence, unveils “Katya – The Informer.” This novel, marking the second foray into a gripping espionage series, plunges readers into the life of Katya Petrovna, a daring character who straddles the fine line between courage and recklessness. Petrovna’s journey from the Russian Federal Security Service to the heart of the G8 Intelligence Agency is more than a career shift; it’s a dive into a whirlpool of danger and moral ambiguity.

The essence of Katya’s story is her first assignment: to infiltrate a mafia-controlled casino on the Black Sea, a mission that promises to stretch the limits of her resilience and wits. As she navigates through layers of corruption and the terrifying underbelly of human trafficking, the narrative unwinds into a complex web where loyalties are tested and the price of failure could mean death. Through the character of Katya, Bickford not only crafts a tale of high stakes and suspense but also offers a window into the sacrifices and the often unseen battles fought by intelligence operatives.

David Bickford’s background as a former Director of MI5 and MI6 lends an air of authenticity and depth to the narrative. His intimate understanding of the inner workings of international espionage and counter-terrorism enriches the novel, making it not just a story, but a reflection of the real-world challenges faced by those in the intelligence community. The acclaim surrounding Bickford’s work is a testament to his skill in weaving complex narratives that are both thrilling and thought-provoking.

“Katya – The Informer” is not just a novel; it’s an exploration of the human spirit, of the lengths to which individuals will go to fight against the darkness. It’s a narrative that underscores the bravery of unsung heroes and the complexities of a world that thrives beneath the surface of what we see. In telling this story, Bickford invites readers to question, to reflect, and to admire the resilience of those who navigate the shadowy corridors of espionage, making sacrifices that often remain unrecognized. This is a tale for anyone captivated by the allure of spy fiction and intrigued by the moral dilemmas that come with defending one’s country from the shadows.

No single mistake was fatal on its own, so no one person could be blamed. The errors and misjudgements were each small, understandable, and evenly distributed.

It was Catherine’s doctor who’d predicted that after two late births, the third was unlikely to be premature.

It was her husband who’d checked the morning wildfire reports and confirmed their home was safe, but been in a business meeting when news broke that an unpredicted diablo wind had changed the blaze’s course.

It was her technophobe mother who’d left her own cellphone in her car, then knocked Catherine’s charger out while tidying, so that the battery drained and her husband’s warning calls from the city went unheard.

It was Catherine who’d dismissed the first mild contractions as cramp, drawing on memories of her previous induced and agonising births.

A few minor missteps, that was all, right into the snapping jaws of disaster.

When her waters broke, Catherine understood her mistake. The baby was coming a month early.

Rushing through the front door to go to the car, her mother froze, as if someone had paused a movie. They both stared at the black smoke pluming on the horizon, where the only road from the cottage led.

After a brief, frantic discussion they decided to drive. Maybe the smoke wasn’t near the road, perhaps that was a trick of the wind.

Her mother’s cellphone was where she’d left it, still charged and flashing missed calls. As her mother drove, Catherine called her husband back, fingers fumbling, but after a long silence in her ear she checked the display and saw no signal. She surrendered to the panic clawing at her throat.

That earnest young man who’d visited last year to talk about wildfire preparedness had said cellphone towers were fireproofed to withstand all but the fiercest blazes. What else had he said? Why couldn’t she remember?

They were cresting the hill overlooking the next valley when they saw the fire, vastly wider than the road it had swallowed whole. It was a glowering orange wall: angry, hungry, racing. Even from a distance, its heat pushed through the windshield glass.

They u-turned, her mother babbling that help would come, everything would be okay. Catherine didn’t talk at all. She needed to think, be sharp, but then a contraction scattered her thoughts like pins in a bowling alley.

Back inside the cottage, her mother scurried, closing windows and doors. Catherine lay on her back on a rug by the bay windows and looked to the skies. Last year, she’d seen news footage of helicopters rescuing people from fires somewhere nearby. They’d be coming now. They were not on their own. Nobody was alone in the 21st century, not with all their technology, all their devices.

The next contraction came with teeth and in pain’s red flare, Catherine didn’t argue when her mother asked her for the fourth time to please – please, please – take painkillers. Catherine didn’t know how safe they were for her or the baby, but if the pain went away she’d be able to think. Not thinking seemed the most dangerous thing possible right now.

A new contraction attacked – rows of teeth this time, like a shark – and Catherine’s brain curled into a protective ball. She gripped her mother’s hand, surprised by its boniness.

The contraction retreated, the oxys kicked in, and Catherine’s mind calmed and cohered enough for clear thoughts to march through. Thank God the other kids’ school was far away. Her husband would have alerted the authorities. Help was coming.

A tendril of black smoke drifted by the window, finger-shaped, as if pointing the way for a terrible, huge beast to follow.

She could feel how close the baby was. Not now, she thought. We’re not ready.

A memory floated into her mind, something a friend once said. He’d been talking about growing up with abuse, his struggles to leave it behind. “If a baby’s born in a house on fire, it thinks the whole world is on fire,” he’d said, quoting something. “But it’s not true.”

But what if it was true? Not just for her baby. For all of them, all the babies born into a world slowly catching fire. The babies delivered into murderous heatwaves in India, remorseless floods in Libya, devouring blazes in Australia. For the first time, those people weren’t faraway abstractions on half-watched news items. She felt connected to them, one vast family scattered over continents.

Then something shifted inside her and this pain was savage enough to rip through the oxy haze and the baby was coming and all thoughts returned to the brute here, the brute now.

Help will come, Catherine told herself again, even as a smoke twilight fell over the house and she couldn’t see the sky any more.

June, 2015

Sarah woke to green plowing seas outside their balcony, rather than the bustle of the port of Kusadasi, Turkey, as she had expected. She climbed back into the soft king-sized bed with Adam, her husband of four days, and watched the shifting rainbow water patterns on the ceiling of their cabin, felt the vibration of the engines and the gentle movement of the ship.

“For some reason,” she said, “we aren’t in port yet.”

“Good,” said Adam drowsily, draping an arm across her waist, and reaching up under her sexy new nightgown. Sarah turned toward him, her senses blooming awake, with a sharp pull of desire. She touched her lips to his, first gently, then with more urgency. They pulled closer, feeling the exquisite joy of being skin to skin.

Later, as she floated, wrapped in Adam’s arms on a cloud of pleasure, a bell sounded over the ship-wide intercom. She swam with difficulty back to consciousness.

“Attention passengers,” came the Scottish brogue they had come to know so well that week. “This is your captain, Martin Stewart. I would like to make you aware of an occurrence last evening. At about four o’clock we saw people in a small craft on our starboard side, waving, in obvious distress. We turned back. We took them on board and they are presently in our infirmary receiving medical attention. There are six men and one woman. We will take them to safety in the port of Kusadasi, and you will be free to go on with your excursions to Ephesus, delayed only by an hour or so.”

Their captain hesitated, then continued. “Safety at sea in is our first priority in the navigation service so you must understand that this was required.”

This was required. He said it with a clipped finality. The intercom clicked off.

Curiosity and excitement filled Sarah. They had migrants on board!

Both her parents and Adam’s had been alarmed about all the Syrian refugees risking their lives to escape the Syrian Civil War and get to western Europe, and tried to dissuade them from honeymooning in the Greek Isles.

“It’s not safe,” Sarah’s mother had insisted during one phone call. “All the news reports have said that the Greek Isles are inundated. And those people are desperate!”

But Sarah had always yearned to see the Greek Isles. She’d never even been on a cruise. Besides, they could face sudden death in the U.S. by simply driving down their own city’s streets. Was it so much more dangerous on the other side of the world? And would it hurt them so much to see people whose circumstances were less favorable than theirs, to learn first-hand how lucky they were?

Sarah burrowed deeper into the silky sheets and let herself drift. She envisioned the migrants sitting in the captain’s quarters, freshly showered, and wearing white fluffy robes, eating their fill from the midnight buffet and being serenaded by the dining room pianist playing show tunes. She let the movement of the boat rock her back to sleep, but ended up having fitful dreams about the minister and rabbi having a polite debate about forgiveness only minutes before jointly marrying her and Adam. Then she woke to real memories of her parents’ equally polite but hesitant acceptance of their whirlwind courtship and marriage.

“What about your children?” her mother finally asked.

Children seemed so amorphous, so far in the future. Surely all of that could be worked out later. Surely everything was insignificant compared to Sarah and Adam’s desire for each other.

Sarah was drawn to the boisterous warmth of Adam’s family; they welcomed her with open arms. She loved the rituals and holidays, the emphasis on family. Then at the last minute, one of Adam’s orthodox cousins refused to come to the wedding, citing the impossibility of consuming non-kosher food.

“What, are they only coming to eat?” Adam complained, insisting that religion wasn’t important to him. It was important to Sarah, though; she prayed regularly and enjoyed going to the Methodist church, feeling God’s forgiveness as the music washed over her, and being inspired by the minister’s sermons to try to be kind and live a better life. Adam probably wouldn’t care if she continued to go. In all honesty, they had never discussed it.

They met, fell into bed on the third date, and knew within a few weeks that they wanted to be married. Adam claimed that he knew the first night he met her.

In the end, everyone came, except the cousins who kept kosher. At first Sarah had enjoyed choosing which wedding traditions to keep –such as a chuppah and a wine glass to honor Adam’s family. She’d taken pleasure in having the “Lord bless you and keep you, may He make his face to shine upon you, may he be gracious unto you, and give you peace” prayer shared by both Judaism and Christianity. But then the minister had used the wrong prayer, the one used only by Christians, and Sarah wasn’t sure if it was on purpose or not, but there in the middle of her own wedding she found herself gritting her teeth and nearly strangling her bouquet. By the time it was over, she’d been just as relieved as Adam and wished they’d eloped or just gotten married in some vineyard by a friend with a newly minted officiant’s license from the Universal Church of Whatever.

“Attention passengers.” Captain Stewart’s deep Scottish voice cut into her thoughts. Sarah opened her eyes. “We have learned that the Turkish authorities will not accept these individuals, as they were picked up in Greek waters. So we will turn around and go to the Greek island of Samos a few miles from here where we will deliver them to the proper authorities. This will result in a delay of your excursions of about three hours, but be assured we will allow extra time for you to return to the ship at the end of the day. Thank you for your patience and understanding.”

So Turkey would not accept the migrants. Those poor souls must be feeling such panic and fear. Then, she had a more selfish thought: Would their Ephesus tour guide wait for them? It was one of the places she’d most wanted to see. One of her well-traveled friends had told her the ruins were magnificent. An entire ancient city, painstakingly uncovered and preserved to a level that overshadowed Pompeii. Would she give up seeing it in exchange for the migrants’ freedom?

Sarah climbed out of bed, slipped on the new bathrobe that matched the sexy nightgown, and made her way out onto the narrow balcony to see if she could see anything. Once outside, the whistling wind caught her hair and sleeves. She gazed at the shifting sapphire water below, and the faint emerald line on the horizon that must be the coast of Turkey.

“We’ll just miss a few hours of those ruins in Turkey, right?” Adam, awake now, propped himself on an elbow in bed.

“Just those ruins? That’s one of the things I wanted to see the most!”

“Hell, you see one pile of rocks, you’ve seen them all,” Adam, grinning, shrugged into a T-shirt and joined her on the balcony.

“Adam! You’re teasing me, right?”

“Yes,” he said, putting his arm around her. Then, “No. I really do hate ruins. Do you care if I just stay on the ship and catch some rays?”

Sarah glared at him. “You’d let me go ashore in Turkey by myself?”

“You wouldn’t be by yourself. There would be three thousand people from our ship with you.”

She stuck her tongue out at him, then changed the subject. “Imagine what it would be like to be in a tiny overcrowded boat out there in all that water,” she said. That heaving, bottomless water. “Being so desperate to get to a new country.”

Adam leaned against the railing. “My great-grandfather was illegal. He came over with his younger brother Max hiding in the engine room of a cargo ship. He was about fourteen.”

Sarah turned to look at Adam. She loved the deep blue of his eyes. He was the only one in his family who had them. “Really?”

“Yeah, it was just after 1900 sometime, I’m not sure exactly, during the Russian pogroms in Latvia. My great-grandfather was the oldest of seven boys, and they were kidnapping Jewish boys and making them march at the front of the Russian army. So his parents sent their two oldest sons to America.”

“They sent the boys by themselves. To a new continent.”

“Yeah. They gave some guy money to bring them food but the guy took the money and spent it on booze and never brought them anything to eat. So, they were hiding in the engine room for something like three days. They licked the condensation off the engine room pipes to survive.”

“Oh, those poor boys. So, what happened?”

“My great-grandfather used his shoestring to scratch a note on a piece of paper they found, and dropped it down when someone walked by below. The guy picked up the note, then wadded it up and threw it down, and he realized the guy couldn’t read!”

“Oh, no.”

“Right, and so then they had to wait hours until finally another guy came and found the note and brought them some grapefruit juice. And then he smuggled them off the ship when they landed, and they eventually found their way to New Jersey.”

“That’s an amazing story.” Sarah thought Adam’s family had a much more difficult and interesting past than her own, with her mother’s grandfather immigrating legally from Italy, and her father’s great-grandfather coming over from Wales after the slate mines closed. She brushed a lock of hair off his forehead and leaned back against him, admiring Adam’s family all the more.

Adam shrugged. “Probably a lot of people have stories like that.”

An hour later, Sarah stood on the balcony as their ship dropped an anchor the size of a minivan a quarter mile out from the small, anvil-shaped port at Samos. A smoky-looking mountain rose in the near distance. Many of these islands did not have ports deep enough for the cruise ships and visitors had to take tenders from ship to shore. Since they hadn’t originally planned to go to Samos, Sarah had looked it up in the book on the Greek Isles she’d bought for the trip.

“You’ll be fascinated to know that Samos was the home of Aesop,” she told Adam, who was sitting in the easy chair watching the cruise channel on TV.

“As in the fable of the tortoise and the hare?” Adam’s eyes didn’t leave the screen.

“Yes. And it says here he was a slave. I never knew that.”

“Me, either.”

A tender with the blue and white Greek flag flapping bravely in the wind began to putter out toward them from the port. Greek soldiers in their blue hats and gray uniforms stood on the dock.

She and Adam stood on the balcony, gently buffeted by the constant ocean breeze, and watched the dogged approach of the tender as the brilliant sun sparkled on the azure, nearly translucent water.

The tender tied up by the forward door and, while Sarah and Adam and dozens of other passengers watched from thirteen floors of stacked balconies, the white-clad cruise crew escorted the migrants onto the tender. The migrants did not wear the fluffy robes of Sarah’s imagination, but bright orange life vests, and an assortment of hoodies, jeans, and camouflage cargo pants. The one woman wore a light purple hijab. Several carried backpacks, while one simply carried a black trash bag, stuffed full. One of the men wore red low-top Converse sneakers. The people were talking and gesticulating, but because of the wind it was impossible to hear them.

As the tender pulled away from the ship, some of the people on the balconies began to applaud, as if they were witnessing something good and right.

Sarah clapped, too, but then saw that Adam wasn’t.

“Our giant cruise ship gave these migrants a ride for a few hours,” said Adam. “Sure, we’re a bunch of heroes.”

Sarah’s cheeks burned at the thought of having applauded when Adam disapproved of it. Yet a desire to defend herself arose.

“I was admiring the bravery of the migrants,” she said. “And some of the cruise ships don’t even pick them up. They sail right by. Or sail over them. At least Captain Stewart picked them up. And helped them. Like that guy helped your great-grandfather.”

Adam didn’t answer. They watched in silence as the tender carried the exhausted, huddled people toward shore, where Greek soldiers waited. The migrants nearly fell out of the tender onto the cement dock in their joy and eagerness.

Then Sarah felt the deep rumble as the captain began to raise the anchor and the faint vibration as the massive engines re-engaged. In a matter of moments, the port of Samos began to slide away.

A few hours later Sarah and Adam disembarked at the port of Kusadasi and found their guide, a handsome, impeccably dressed, dark-haired young Turk holding a placard saying “Sarah.”

“I am Emir.” He did not smile. He shook Adam’s hand first, then Sarah’s.

“I’m sorry we’re so late,” Sarah said. “I assume the staff told you what happened?”

“Yes.” He gave her an annoyed look. “Please to come along to the car.”

Sarah felt uncomfortable; already she knew Adam didn’t want to be here. And now clearly their guide was displeased by their tardiness. This did not bode well for the day. Sarah and Adam hurried so as not to lose the back of Emir’s fine leather jacket in the crowd of tourists as he walked briskly toward the street, clogged with cars and minibuses cutting from lane to lane, blowing horns. He introduced Ali, the driver of a shiny black car, and they hopped into the back seat and scooted off through the busy, meandering streets, ripe with the smells of gas, leather and kebabs.

“The city of Ephesus used to be on the coast of the Aegean, but because of silt accumulation, after centuries, there was no water access, and the city was abandoned. So now water is two miles away,” Emir explained as they wound through Kusadasi. On the outskirts of town, he pointed to massive columns along the road. “These were part of the aqueduct that was built by the Romans, one of the most advanced of the modern world.”

When they arrived at the ruins, Sarah could see a long road lined with tall, imposing stone edifices.

“Ephesus was originally a Greek city founded ten centuries B.C. Over the centuries it has been conquered by Alexander the Great, later the Romans, destroyed by the Goths, later by an earthquake, and finally conquered by the Ottoman Turks.” Ali stopped the car and Emir jumped out. “See you in three hours, Ali.” Emir slapped the top of the car.

“Ok.” Ali zipped away as soon as they climbed out.

“We will enter here,” said Emir, pointing to the gleaming white stone road. “Please to be careful of your steps. The ruins of Ephesus were discovered in 1874 by John Wood, a British archeologist.” Emir led them down the long street, stopping to show them the Temple of Hadrian, the terraced homes on the slopes of the hill that were occupied by wealthy Romans, and the famous Library of Celsus, with its regal columns. The blazing sun bore down on them and the white stones gleamed. Sarah could not shake the feeling that Emir was rushing them. They walked farther down the street, where Emir pointed out a row of what looked like very public stone toilet seats.

“What would you think these are?” he asked.

“They look like toilets,” Adam said.

“This is correct. These were toilets for the men. They would sometimes have their slaves sit on the toilets to warm them before they sat there.”

“What about the women?”

“Behind a tree,” said Emir, with a quick grin.

Sarah drew in her breath. It was thousands of years ago, but still.

As they made their way farther along the street, Emir pointed out ancient stone food stalls that were, he said, “the Roman equivalent of McDonald’s.”

At the bottom of the hill, they took a turn and came to a field edged on two sides by the remains of what seemed to be merchants’ stalls.

“This is the Jewish section of Ephesus, where the merchants had their stalls. Ephesus was considered a socially advanced city, where strangers were allowed to integrate.”

“Nice of them,” Adam said with a dry chuckle.

“The apostle Paul lived in Ephesus for three years,” Emir went on. “He originally was a member of the synagogue, but later moved his teachings to a church.”

“Oh – I remember — the letters to the Ephesians in the Bible.” Sarah vaguely remembered studying Ephesians in a college course.

“Yes,” said Emir.

She glanced at Adam but he had a blank look. Oh right — Ephesians was in the New Testament. She searched her memory from her class. “I think Paul wrote the letters to the Ephesians from prison in Jerusalem. In the letters Paul said that Jesus’ teachings brought down the walls dividing people and promoted peace.”

Adam shrugged. Sarah realized that she believed this and Adam didn’t. A cold sweat broke out on the back of her neck.

“Paul had converted many citizens of Ephesus to Christianity,” said Emir. “And it was hurting the business of the artisans who sold the silver statues of Artemis. There was a kind of riot, and he had to leave town. I am Muslim so I do not know any more about Paul.” He headed down the road toward the next group of ruins.

“Religion!” said Adam, as he and Sarah followed Emir. “Every war ever fought was caused by religion.”

“That’s not true!” Sarah said. “I think people use religion as an excuse for wars, but they’re really caused by greed.”

“All religion does is divide people!” Adam shot back, veering away from her.

“Well, religion was made up by mankind, so of course it’s not perfect, because people aren’t perfect,” Sarah said. Sweat was now running down her temples and ribcage as she walked. “But don’t you believe that God is still God?” She heard a new shrillness in her own voice.

“I don’t believe in God.” Adam walked ahead of her and caught up with Emir.

Sarah stood in the dusty road. He’d told her religion wasn’t important to him. He’d never said he didn’t believe in God. Cold shock jolted the center of her chest.

There suddenly seemed to be a chasm between them, when just this morning she had never felt so close to a person.

She caught up with Emir and Adam at the foot of an enormous ancient open-air theatre. She suddenly felt very tired.

“It seated twenty-five thousand,” said Emir. “Do you have any questions at this point? Since we were delayed, I will give you only the highlights of the rest of the site.”

Sarah felt a rise of indignation. “The delay was no fault of our own,” she said.

Emir immediately became very animated, gesturing with his hands. “The captain should never have picked up those migrants! It is up to the captains, they make the decision, and they think they are doing something good, but now see how it affects everyone! I had another tour later today which I must reschedule. It affects my livelihood. We have thousands of migrants in our country. Turkey is completely overrun. They cannot work, they cannot contribute to our society. They are nothing but a drain. It’s an affront to law-abiding citizens of Turkey!”

Sarah and Adam both stared at Emir with open mouths.

“Some people in the U.S. feel the same about immigrants,” said Adam.

“I hadn’t thought about how the delay affected you, or how the migrants affect the citizens of Turkey,” Sarah admitted to Emir. “But still, those people needed help.”

“Outsiders do not understand our situation here.” Emir turned abruptly and walked toward an open area he described as the agora, or marketplace. As she and Adam followed Emir, Sarah found herself wanting Adam to take her hand, but he didn’t. In a robotic, hurried voice Emir pointed out the ruins of the temple of St. John, and then the scanty remains of what was once the Temple of Artemis, once considered to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. “Artemis was the goddess of chastity, the moon, and the hunt. This temple was thought to be originally four times the size of the Parthenon,” he ended.

It was clear to Sarah that Emir had made up his mind to truncate their tour and there wasn’t going to be anything she could do about it. She glanced at Adam and saw that he was bored, anyway; as far as Adam was concerned, the shorter the tour, the better.

“Now, do you want to go to the house of the Virgin Mary?” Emir said. “It will take approximately one hour. It is on top of that hill.” He pointed to a small mountain in the distance, then glanced at his watch.

“No,” said Adam.

“Yes!” said Sarah.

Emir glanced at Adam and then at Sarah with exasperation.

“Yes, I do,” Sarah said. “I read about it. There’s a wishing wall there, Adam, where people write down their prayers and wishes for the Virgin Mary. I wanted to do that.”

Adam and Emir shared a look.

“We’ll never be here again!” Sarah said with desperation in her voice.

Not far from Ephesus, at the peak of a small mountain, stood the House of the Virgin Mary. Sarah had read that it had possibly been built for Mary by the apostle John. The small stone house had been converted into a one-room chapel with a stone altar, a statue of Mary, and a Turkish rug on the floor. Sarah had read that Mary lived here from the time of Jesus’ death until the time of her assumption, sometime, possibly, between 43 A.D. and 50 A.D. Three popes had visited this chapel.

Sarah stood inside the dark, candle-lit chapel for a few minutes, quietly admiring the gentle, gracious statue of Mary. She’d left Emir and Adam outside waiting, Emir focusing on his cell phone, Adam drumming his fingers on the picnic table. Now she watched as an elderly man and wife, holding hands, went to the altar and lit a candle. The tiny flame leapt toward the shadowed ceiling. Sarah didn’t light a candle; she wasn’t sure but wondered if one had to be Catholic to light one. One of her Catholic friends said she lit a candle for her mother in every chapel and cathedral she visited. Sarah watched the way the elderly couple moved together in synchronous harmony, and wondered how long they had been married and for whom they were lighting their candle. It seemed so clear that they shared a faith.

She gazed at the statue of the virgin for long moments, trying to absorb peace and love from her. At last, reluctantly, she turned to go.

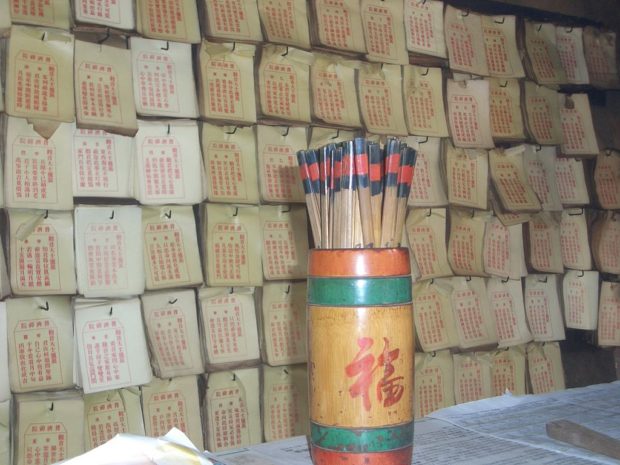

Outside, Adam and Emir rose to their feet as she exited the chapel. Adam looked at his watch. But Sarah still hadn’t made her wish at the wishing wall. The stone wall, seven feet tall, was covered with thousands of scribbled paper prayers. The white papers had been wedged in between the stones and had clung there through sun and wind and rain, blooming like a profusion of fluffy white flowers covering every inch of the surface. Sarah stood still and drew in her breath, taking in the yearning and nearly holy beauty of it. She carefully framed a picture with her phone because the image was one she didn’t ever want to forget.

In a small alcove in the wall were pencils and papers. She held up an extra paper for Adam. “Make a wish, Adam,” she called.

He shook his head.

She watched the elderly couple together wedge their wishes into a chink in the wall, their gnarled fingers touching, and then she scribbled her own.

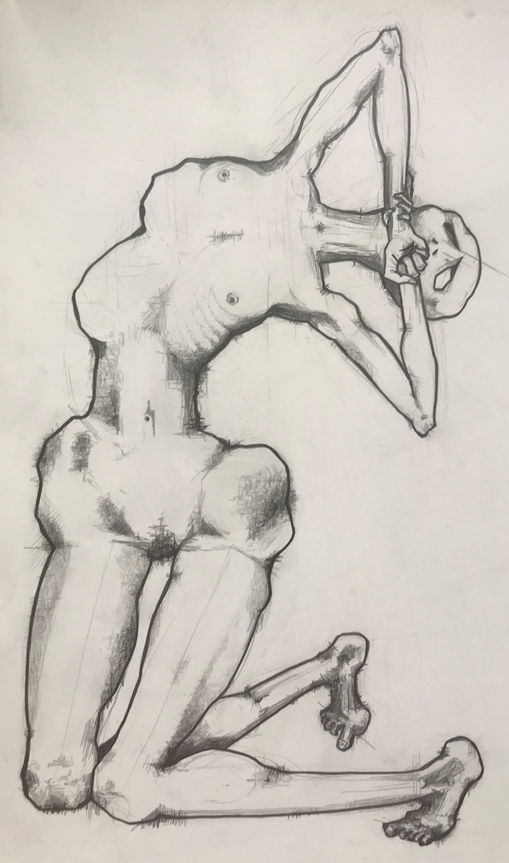

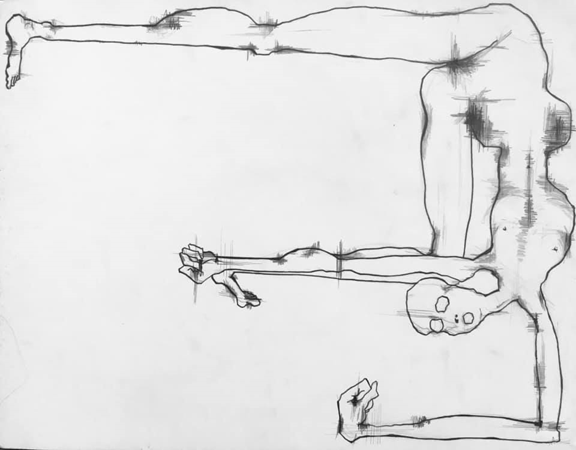

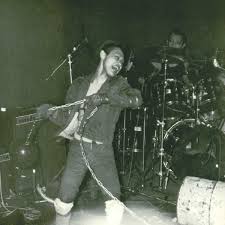

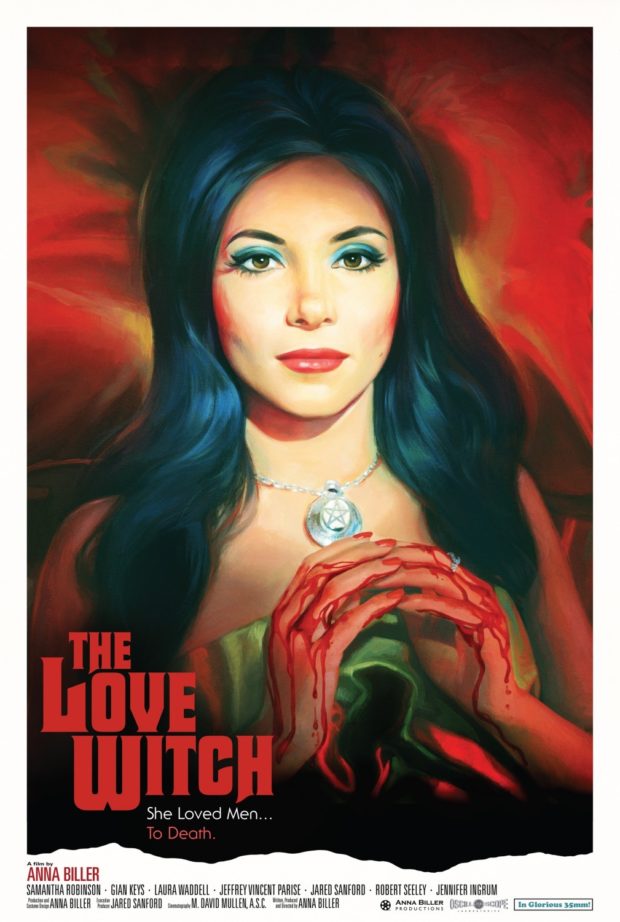

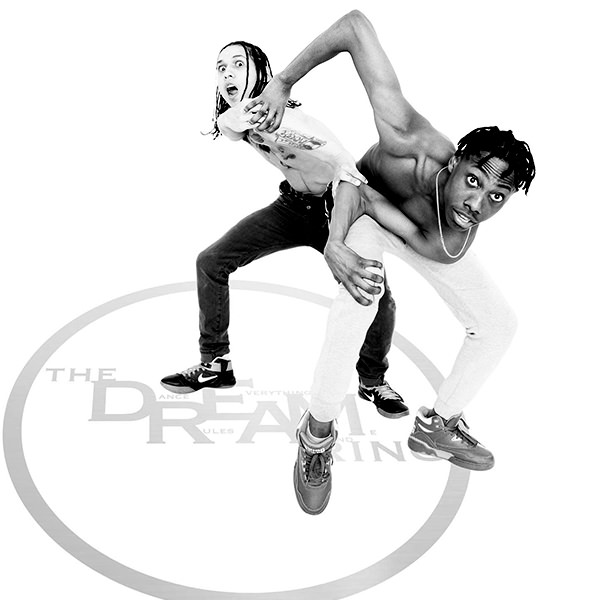

The male body is an object of fascination in Breaking Kayfabe, Wes Brown’s shapeshifting autofiction on his unlikely career in UK pro wrestling. We begin with the narrator as a child observing his sleeping father, the real-life 1970s wrestling legend ‘Sailor’ Earl Black. Wes looks down on “the wreckage of his body,” his “washed up bulk.” One leg is fused stiff, part of his spine is missing, his “muscular canvas” is painted with faded tattoos, and his teeth float in a glass of water.

Brown poignantly captures the dual sensation of awe and disgust which the child feels on seeing old bodies. Through these eyes there is something mythic and heroic in the broken body. Only an adoring son could see this type of masculinity and dream of becoming it – which, of course, Wes does.

Men’s bodies in this book, like their minds, are battered and bruised, often intentionally. It illuminates the reality of the strange “mythic realm of wrestling”: men throwing themselves around for other people’s – usually other men’s – entertainment. Reading the book, you realise how little this type of masculinity is seen in modern literature and wider culture.

Skip ahead to Brown in his late twenties, after a stalled literary career and an identity crisis, and Breaking Kayfabe sees him live out the childhood dream of following in his father’s Spandex.

The product of four years of real-life wrestling, followed by four years of writing, this is an impressive and distinctive work. Its indie publisher, Hebden Bridge-based Bluemoose Books, is home to the 2019 bestseller Leonard and Hungry Paul by Rónán Hession and was the original publisher of Benjamin Myers’ Pig Iron, earning it glowing write-ups in The Guardian as “a small but mighty literary hit factory.” Brown’s book deserves to be among Bluemoose’s best read and most lauded of the year.

Breaking Kayfabe follows a familiar arc as Brown’s character goes on the journey from a rookie wrestler, or “strawb,” to becoming a UK champion, in the process cultivating his persona as a baddy, or “heel.” The bulk of the story is told in the backroom and in the ring at wrestling shows, with fight scenes which are dramatic, fun, and accessible, and depictions of Brown’s fellow wrestlers full of humanity and humour.

So far, so usual. But the text handles these wrestling tropes in such a considered, thoughtful way that it takes the reader deep into the subculture’s psychology; the effect is enthralling. Bodies sustain real injuries in staged fights. Outside of the ring, wrestling caricatures take over their hosts. To ask if wrestling is real or fake is to ask the wrong question. The right question is, why do we invest so much in fictions and what does it do us?

For Brown’s character, wrestling and writing are inextricable from his sense of self. He writes, “I was always convinced I was never enough and always had to reach to be something else, something that wasn’t me and that was the way to be successful.”

So, this is a book as much about writers and writing as it is about wrestlers and wrestling. Breaking Kayfabe is billed as Brown’s debut novel, but some will recall an ill-fated proto-debut in his early twenties. Ill-fated because he cultivated a “contrarian intellectual” persona which felt false, and he spent time on the literary circuit feeling like “a coward, an imposter” and “a liar, a bullshitter, a charlatan.” This is raw stuff. There is real honesty and pathos in the image: the lost young man who presents a façade to the world, feels a fraud, turns to drink, and implodes.

Contrast that with the assured and grounded writing on the page in Breaking Kayfabe. Brown cleverly allows the reader to draw parallels between the “Strong Style” he seeks in wrestling – a more physical, combative style compared to light-touch staging – and the strong style he aims for in writing. Brown never defines that literary ‘strong style’ for the reader, he leaves it on the page. But we are told that “I had lost faith in novelly novels. In their fake plots, fake events, fake characters.” The prose is no-nonsense, never elevated and overly stylised, nor style-less or macho. This is high-impact prose, unflinching, emotive, and crisp. The preciseness within sentences and across the whole structure is a credit to the writer and editors. And in a text where style constitutes identity, the author’s ongoing search to find their voice has never been so vital.

The parallels between wrestling and writing continue in the middle-lands of kayfabe and autofiction. In wrestling, kayfabe exists in a creative space between fake and real, as the wrestlers code of illusion; in literature, autofiction occupies that obscure place between fact and fiction, or within both. All this metafiction and autofiction could be wearying, if it wasn’t handled so adeptly and set within an irresistibly simple rookie-to-champion arc.

Wrestling drives the story in this book, it’s the source of the protagonist’s dreams and the stage for Brown’s philosophy on masculinity and much else. But he also invites us to see it as a foil, a MacGuffin. Alongside his “Earl Black Jr gimmick,” he writes of creative writing lecturing as his “Mr Brown gimmick.” Naturally, we wonder what constitutes his ‘dad’ gimmick, his ‘boyfriend’, his ‘son’ gimmick. The word gimmick, here, does some unusually heavy lifting in terms of the masks we wear. If every role and relationship in our lives is a mask of sorts, then what of our identity? He writes:

“It was becoming difficult to tell where I ended and Earl Black Jr began, but I didn’t care. I liked feeling his black blood in my veins, like a poison, a Venom symbiote I had invented, made up of parts of myself I had repressed.”

This brings us back to the point of men and their place in the world, or as Brown puts it, our “fictions of masculinity.” Brown writes objectively of how “macho was crude and backwards” and how wrestling gave some men the outlet to perform their fantasies of masculinity. Ultimately, the narrator journeys out of the myth, having come through his childhood awe, seen past the heroic image of his father, and decided that “I didn’t want to live with any more illusion than I had to.”

Brown navigates all this smartly in a fast-paced, entertaining read, leaving the reader with questions and impressions which last long beyond the final page.

Breaking Kayfabe by Wes Brown, Bluemoose Books, May 2023, 290 pages.

Want to try your own hand at autofiction? Know how to write from lived experience, and turn memories into stories?

Sign up now to “Writing Your Truth”: a two-week masterclass with award-winning and Women’s Prize for Fiction Futures shortlisted novelist, Jessica Andrews.

autofiction Bluemoose Books essay masculinity review wes brown wrestling

The wall has come together over many generations. First, the flint base, a layer of fist-sized, glassy cobbles. Then stone, boxed chunks of it, the same sickly grey as the Chapel of Our Lady – or what’s left of it in that rubble pile, sprung all over with nettles and creepers, a few fields away. Next is brick: flat red Tudor tiles, sandwich-thick, and ruddy Victorian kiln-fired brick, mottled and liver-spotted with age. Cement-and-rubble-patches plug gaps where the wall has narrowed and sunk. The top is banked up with whatever’s come to hand: shingles of slate, bottles, broken pot. This is not a wall for scaling.

The wall is stitched together with ivy: not so much a climbing plant as a tangle of limbs branching and pushing through the mass. The stems are thick as thumbs. At the base of the wall, the foliage is so dense it’s impossible to see where the plant begins. Layers and layers of suckers have scaled up and pooled back down, rooting themselves in the ground until a second wall, green and glossy and knitted with webs, stands before it. Both wall and ivy cladding are the work of ages.

The wall runs along the edge of the field, bordering part of Hill’s garden. It peters out at the crossroads just below the village, ending in a craggy line where a gate or archway once stood. Hill can see into the field from the upper rooms of the cottage. A thick steward margin stands on the far side of the wall, a wide belt of unploughed soil between the ivy tangle and crop line. Lines of glossy beet leaves crosshatch the field, the damp rows stalked by hunching rooks.

Hill’s garden shears swing long and low in one hand, nudging her shin. Though the ivy hasn’t been trimmed for years, at least there are no brambles. Those spiked limbs have made a season’s headway on the shed, hump-backing the roof with arches of thorn and ripping at the felt. But there are no brambles on or near the wall.

Where to start? Hill scuffs a boot at the lawn’s edge. The grass was knee-high beside the wall before Mr Bailey, the local odd-jobber who’d been helping out, agreed to trim it. Even then there were no brambles. No chickweed or thistles or dandelions. No alexanders. Not even bindweed. Nothing has seeded in the grass; nothing has taken root in the wall. The ivy is like a shield.

Mr Bailey wouldn’t tackle the ivy himself. Hill offered him an extra day’s work to do it, but he said it was best to give the wall a wide berth. Hill said she wanted to make a feature of the wall, and if part of the ivy could be cleared, she reasoned, at least at the near end, then something else could be grown against it. A clematis perhaps. Mr Bailey said that disturbing the ivy would do more harm than good and that if part of the wall should come down, it would be a job and a half to fix.

Hill does not wish to make a feature of the wall. It is hideous. Hateful. She wants to tear it down, knock through it, level it and skip the rubble. The top of the wall is little more than a spoil heap. It is not a scheduled monument; no regulations protect it. But she knows it’s impossible. The wall abuts the field and she would need permission from the farmers to clear and replace it, agree the details of demolition and removal, arrange access for trucks in the field, compensate for any damage or inconvenience.

For now, she can only tackle the ivy, but it’s a start. It isn’t safe to take a strimmer to it, not with all those loose stones and the possibility of hidden glass or metal. It’s the shears or nothing.

Hill gets to work.

The keys have been theirs for a week now. A lot of the furniture has gone. Hill has kept the pieces worth saving: the dresser, built to fit the space; the workmanlike kitchen table; the old fireplace and mantelpiece. The cottage is attractive enough and the setting rustic, even if the village is little more than a residential street now, the shop and single pub long converted to housing. Hill will pitch the place as a get-away, an escape from the bustle, a chance to return to a simpler life. The nearest decent supermarket is fifteen miles away but there’s a small town just up the road with a couple of cafes and a convenience store. There are footpaths to explore and a reservoir for fishing. Robert’s aunt employed a local cleaner towards the end, and Hill has already arranged with her to see to the place between bookings.

Robert is keen for the place to pay for itself; says it’s impossible they will ever live here. Hill has made improving the cottage her project: a place to exert her control, her taste. At first she pictured spending long weekends in the cottage, imagined rambling country walks around the lanes, returning to a casserole in the oven, a stack of logs and a pile of books to read. She saw herself alone here, lying in a bed heaped with blankets, listening in the dark to the creak of frost on the windows, the hoot of a tawny owl hunting. Robert did not feature in those fantasies. Robert did not exist outside the city.

Could she? The longer Hill is here, the more she misses the flat. Not the space itself, but the reassuring trappings of routine. Coffee from the deli at the end of the street. The bus grinding through morning traffic. The grim, silent camaraderie of the daily commute. She will not admit it, but perhaps Robert is right. Perhaps she is not cut out for the cultural privations of country living. But her job is soulless: pointless, purposeless. Her labour makes no discernible impact on the world. Who would care if she never returned? What difference would it make to anyone? She could stay here in the country and let it winnow her to nothingness.

Well, she is here now. She will shape the place and leave this trace of herself, if nothing else.

Hill hacks at the ivy for an hour or so. It’s hot work and every now and then she wipes sweat and dust from her eyebrows. Even so, she hasn’t made much of a dent in the foliage, just a shallow square. Her nose itches. She rubs at it with the back of her gardening glove, smells the bitter crushed juices of ivy, acrid on soft leather.

She’s given up looking for the base of the plant. Anything above chest height will eventually come down when she cuts through the lower layers. She’d hoped to tug out some of the length as she went, cutting the ivy off at the waist and reeling it towards her, but the tangle is so dense she can’t pull anything free. Instead, she is barely sculpting it.

Hill steps back from the puddle of glossy leaves at her feet. Maybe if she waits, the severed lengths will dry out and come free. A week or two of weather might see to it. She studies the thick cobwebs in the flint of the wall: for all these nests, she has yet to see a spider.

Hill tests the depth of the ivy with her arm. She can’t quite reach the stone of the wall, but she’s close. She wiggles her gloved fingers towards it. There’s something small and white in there, resting, just to the right and out of reach, between two stone blocks. Not resting – hanging, suspended in the ivy. Something about the size of a ping pong ball. Hill retreats to pick up her shears and presses back into the mass, parting the curtain of foliage with the tool’s long, scissored points. She wiggles a gap in the ivy wide enough to see the object clearly. A small bird’s skull.

The poor thing must have nested against the wall and died there. The ivy has pushed through an eye socket, threading a bead. Hill can see no skeleton; maybe there is only a head, the abandoned trophy of a cat kill. The cat must have left it on top of the wall and it fell down into the ivy. Or the plant, leafy fingers reaching, picked up the skull and carried it as it grew.

Hill is exhausted. Her head throbs from exertion and concentration. She sneezes; stretches; yawns. It’s already getting dark. She toes the shorn leaves together into a small pile and heads back to the house.

It takes Hill three days to make any kind of hole in the ivy. Robert is back at work, too busy to take more leave. It’s up to Hill to keep going with improvements on her own, which suits her just fine. There isn’t much she can do in the house yet, not until new furniture arrives. It makes sense for her to carry on working in the garden.

Hill feels the woozy fog of an impending cold: it’s typical she should get sick when using up precious holiday allowance. She must have disturbed an allergen of some sort too, because a raised rash has planted itself just above her wrist. The rash has tracked its way, dogged, day by day, along the inside of her right arm.

Hill’s nose streams and her breathing grows ragged. But the cold fresh air is surely good for her, so each day she works a little in the garden, hacks a little more at the ivy. At night she sleeps propped up against pillows, almost seated. Her dreams are gothic: of sinking into a thrashing sea; of dust and cobwebs and sheets draped over furniture. Of a living burial she cannot prevent, a distant rectangle of daylight above her, Robert’s face long and pale looking away as he scatters her with handfuls of soil and leaf mould. She wakes in the early hours, gasping, swollen-mouthed.

Robert calls on Thursday evening. He has a late finish the next day. There is so much for him to clear that he will need to work on Saturday. It hardly seems sensible for him to make the journey to the cottage, not just for one night. He would have to leave again on Sunday afternoon anyway. Hill listens. She holds the receiver away and breathes through her mouth. She does not want him to hear the crackling of her lungs, the thickness of her phlegmy voice, the unspoken suggestion of her not-coping. She hums responses: hmm, all is fine. Huh-hmm, she is making progress. Nuh-hmm, she doesn’t need him to be there.

He doesn’t want to come and she doesn’t need him hovering around, judging what she has or hasn’t achieved, expecting meals, criticising her decisions or her ragged, raw-nosed appearance. They are both keen to keep the call short.

The next morning, Hill stares at the wall through the kitchen window, sipping a mug of coffee she can barely taste. She is not making progress. She will not let him see that. She will not let this ivy defeat her.

Hill applies a layer of antiseptic cream to the rash on her arm. The red bumps are disturbing to touch, the feel of blood so close to the surface, the puckered skin rippling pale then blushing again as she rubs in the cream. The bumps have started to join together, clustering, converging, forming meandering tracks connecting dense constellations of blistering, fluid-filled crimson. The cream stings and sticks Hill’s prickling flesh to the inside of her shirtsleeve. It aches to raise her arm. But Hill is determined. She takes the heavy shears from their hook and returns to face down the wall.

In the late morning she finds a decaying mouse, hanging, like the bird skull, in a looped stitch of ivy. Another cat victim? As the light starts to seep away and the shadow of the wall spills into the garden she finds a dead rabbit, back foot caught in a snare of foliage. It has been there a while, the body parched and leathery, but patches of the underbelly fur and tail are still white in places, still heartbreakingly bunnyish and soft. It must have come from the field and squeezed through a gap in the wall. Did it get tangled and break its leg? Was it sick or wounded, holing up somewhere safe, buried in the dense green to escape a predator? Hill shudders as she cuts the ivy away from the small body and it falls, slight and loose, into a pile of trimmings. She fetches a spade, scoops the creature up, cradled in the wide cup of blade, and carries it to a flowerbed. She digs a hole beside a rhododendron and tips it in.

Hill coughs hard that night: a wet, wracking cough that makes her back and sides ache.

On Saturday morning her glands are swollen. She takes three paracetamol and wraps a scarf around her neck. She stands at the window and looks out at the wall, shifting, unsteady, from foot to foot. Her mouth tastes rusty, astringent. She spits into the sink and turns the tap on hard, looking away, terrified of the poisons exiting her body.

On Saturday evening, Hill finds a fox. At first she thinks it might be a cat, the villain responsible for those smaller kills, but then she sees the orange brush of tail poking through gaps in the plaited ivy. The plant has twined itself round and round the fox’s body like a child wrapping string around a parcel. She tugs at the encircling ivy with her shears. Part of it falls away and the fox’s head droops and swings. She turns aside and vomits onto the grass.

On Sunday morning, Hill’s right armpit is aching and swollen. She has trouble swallowing painkillers. She cannot raise the shears above knee height; cannot bear to remove the fox; cannot bring herself to work on the same patch of ivy. She snips at a low piece of foliage, skirting the grass. She coughs and coughs: and spits blood.

Fear pricks her. She bends over, hands on knees, pinpricks of light clustering in her vision. Standing again she drops the shears, rocks and sways.

Hill lists to one side, striking out her left hand to catch herself. Her gloved palm reaches into the mesh of ivy; through it; meets the wall. She hears the delicate crunch of contact; feels a tearing and searing ripple through her from wrist to shoulder to neck.

The numbing embrace of the ivy supports her torso, cushioning, drawing her in to rest. Her head swims as she sinks in, down, luxuriating. Dust and trapped pollen, soil and wood and sap-spice: she breathes it in, deep. Yes, she thinks, time to let go, time to make peace. She sees the shape of the cottage at the far end of the garden, blurring, beyond the ivy net. It will always be Robert’s cottage. But here it is soft, so soft and shielded beneath the lush dappling, not hostile and other but ageless, timeless. Vegetal. Yes, she will stay. It will always be there to console her, to keep her close to the wall and the earth beneath it; to hold her, comforting and containing, the shallow breaths of grit and greenness slowing, slowing, unfurling into leaf.

Jo entered the field of rough pasture following the footpath signs; the bus revved up negotiating the bends on the way down the hill behind her; then, silence, and the wind in her ears. She looked up at the low clouds and breathed deeply, leaning into the wind, relishing the flecks of rain on her face.

She recollected her husband’s words – “Why on earth do you want to go for a walk on a day like this?” – as if, of course, she was mad to think of it. She knew why, but found it hard to explain.

In the corner of the field an old grey horse shook his mane as if to scatter the moisture. Low grey clouds, chivvied across the sky by a sharp wind, changed shape as they went, fickle as hopes, formless as fears. She trudged up the slope, observing that the field was full of weeds – like those rooted in her marriage – as if fit only to turn an aged workhorse out to grass. Despite her hood the wind lashed hair into her eyes. At length, coming over the rise she was rewarded by the prospect of a green valley, with gently sloping fields bordered by trees. There must be a stream down there, she thought, though as yet she could not see it. Grateful to stretch her eyes over the landscape, she began to assess her route. Once, she had viewed the landmarks of her future – work, marriage, homebuilding, children – as part of a colourful journey laid out before her. Now those milestones were passed, her path seemed less clear.

The going would be easier on the downhill, she thought. But nothing was as easy as it looked. Negotiating prickly entanglements with some brambles, she pulled away, identified the muddy path, and sliding and slipping made her way down to the cover of a sighing wood. As she went, incidents which galled her sprang to mind, one after another.

“Why go out all the time?”

“Because I’m suffocating at home!”

She realised she was shouting. A quick glance around reassured her that no-one could have heard, except for a flicker of feathered rush to a further tree. She spied the red breast of a robin, pertly observing her from a safe distance. With one foot she scraped aside some of the dead leaves carpeting the ground. Then, from a dozen paces away she watched quietly, as the bird returned to forage in the exposed earth. She caught herself planning to tell Ray about the robin on her return.

She pictured him reading the paper, watching afternoon TV, while she attended her art classes, her voluntary shifts at the hospital shop. Activities which it never occurred to him to question while he was working, now had to be justified in an inquisition, belittling, by implication, her friendships and pursuits. Stung, she had once replied, “You should do more yourself, might take off a bit of weight,” and left the room to avoid seeing his face. Hating herself, and yet bursting with irritation, she wondered whether the task of understanding and accommodating their diverse requirements was always to remain hers alone.

Where she sat was sheltered, but the tops of the trees danced, as wildly as teenagers in a night club. She smiled at the memory. Ray had been a real mover; at seventeen, she had been bowled over by his grace and energy. He had not needed her then, with so many admiring female eyes upon him. But now – how could Ray possibly manage without her? Was she staying with him for pity then? Resolutely, she faced the fact that this was hardly adequate for an onward journey.

There was a rich, mouldy smell to the air; branching fungus grew on a long-fallen log. The smell of autumn she thought – a smell of sadness, or perhaps wistfulness; winter lay ahead. Pigeon feathers lay between the path and a low stone wall – the result of a tussle? Or a kill? She rose, finding that her hips ached for a while until she again settled into her stride, through the wood and out into the fields of grass and mown stubble.

Beyond the moving clouds she could see patches of blue sky. Suddenly the world brightened as sunshine turned the mown field to gold. She pushed back her hood and enjoyed the light breeze in her hair and the sensation that unexpected pleasure could still attend her journey.

At the next stile she sat for a moment in the warmth of the sun, watching the patchwork of rainclouds in their steady procession above, and then at the low hills ahead, still in shadow. Beyond them she knew the valley descended hundreds of feet before she would reach home. Now, reluctantly, she faced the fact that she must choose, whether to continue the long walk onward, or cut short her journey, turn back up the path and get the next bus. At a juncture like this Ray would normally reach a rapid decision and head off at a smart pace without waiting to see whether she were in tow or not. She thought about future journeys, and realised that it might be easier to take them on her own. The path passed under a solitary oak, her gaze wandering from the aged limbs spreading in unconstrained vigour to the four winds, up into the glimpsed heights of its rustling crown. Had she reached the heights, or perhaps the breadth, she was capable of?

She had almost decided to abandon the walk, turn back and head upwards, to regain the road before it rained again. She would choose a new path, another day. But she could hear the rush and trickle of hidden water. Beyond the stile, the grassy path ran alongside the stream, sunlight patterning the stones in its brown depths, reminding her of children with nets and jars; of Ray, patiently directing investigations, towelling shivering feet, retrieving slimy waterweed from the brook and setting up a tank with a water pump for the tadpoles in the kitchen. The grandchildren would soon be old enough to enjoy such expeditions.

Ray had spoken of making a pond in the garden. Charming as the tiny frogs had been, and magnificent their leaps out of the tank and onto the lino floor – occasioning shouts and screams in the chase for recapture – she thought a pond might be preferable to the kitchen for future hosting of amphibian life. Maybe other creatures would come, damsel flies and dragonflies. She pictured the dart and dance of shimmering wings. Ray loved invertebrates.

Perhaps in spring… She walked on, and the sunlight came and went. Soon she would again be in gloom. As the path began to ascend once more towards the lip of the valley, a spatter of rain against her face presaged a coming shower. From her pack she checked the map in its plastic cover, traced again her homeward route, and took out waterproof trousers, prepared as well as she could manage, for the rest of the journey.

Chris stirs in the doorway as the early light wakes him. It flows about him, grey and icy. The hip that he lies on is painful but if he shifts to the other side, within a few minutes that will be the same. Lying on his back is worst of all – colder, more exposed, the pain more widespread through his body. He drags a corner of the old blanket over his face, because although the night is difficult, it is more difficult to face the day. He tries to tuck another part of the blanket under his hip, but it will not reach so far. Pain has many shapes and colours, it has techniques and methods, ways and means. He sits up slowly and clumsily, starts to rearrange himself and his belongings. He takes his old trainers from the large carrier bag that is now his wardrobe, suitcase and cupboard; folds the tattered blanket that didn’t quite cover him, and stuffs it into another bag. He pulls out the chunks of old newspaper that he keeps there and stuffs them into his clothes and his trainers where they are damaged.

Chris looks carefully about him. Sometimes he finds bits of food left here in the doorway – a sandwich box, past its date but the contents still edible; a packet of biscuits once, unopened. But sometimes it is just old wrappings, or other rubbish: empty cigarette packets, empty cans,old bus tickets. A pool of vomit, oddly coloured and textured.

He can see a little of the sky from his doorway; he sees a fragment of silver moon there still. Later, the sky is layered, as if an amateur artist had wielded his brush – a long scarlet streak at the horizon, paler clouds above, dusky pink, lemon-green, silver-blue. He notices the colours there, thinks about their names, as if it was the artist’s paint-box.

It’s the best time now, in the early morning, before he is forced to seeonce more that everything close about him is soiled and shameful.

—

“Once upon a time, there was a little girl called Millie. Her real name was Melinda but everyone called her Millie because at first she was much too small for such a big name…” As he reads, the small face beside him changes from serious and intent to round and smiling. “Millie was very special, because she was born on Christmas Day, so that was a very very special day for her. And one year she had a very very very special Christmas present…”

The child presses into his arm, close against him. She is warm in her night-clothes, her copper-coloured hair still wet and dark from the bath.

“…It was from her Uncle Cuthbert…” The name causes a fountain of laughter, and she sits up straight again. “Daddy, there’s no such person as Uncle Cuthbert, you made him up!”

—

But Once upon a time was once upon a time – a time that seems hardly real to him these days, unreal as a child’s story, and long ago. A time before he lost his job, before the drinking, before the slow break-up of his marriage: or was it the job, break-up, the drinking? A time before the long depression, the sleeplessness, the lack of any escape from the problems and the worry, even at night, so that eventually, drink was all that helped. Though it was a brief escape only from the downward track that led to a deeper depression. The depression, the drinking; drinking, depression…

Eventually, after many long months, Emma told him what in some part of himself he knew already. “You’ll have to go, Chris!” She was forcing herself to speak, standing very straight, her back to the kitchen wall, hands clenched by her sides as if for a fight. He saw Millie there for a moment, he saw the same spirit, the same fight. “I tried my best,” Emma said, and he knew it was true. “But this is about Millie – I found her in tears the other day, curled up on her bed. It wasn’t the first time.” Emma had dyed her pale fair hair, he noticed, which was beginning early to turn grey – it was a bright, strong colour now, too bright, like a sunflower. Perhaps she was hoping to find someone else. She wanted another child, he knew, they’d been planning this together before things began to go wrong.

“You’re a waste of space!” she told him, angered by his silence. “Why don’t you SAY something, Chris? Why don’t you DO something, for heaven’s sake!” And still he could find no words to speak, no gesture to make.

“What have you got to offer us now?” Emma asked after a while, more quietly, after another silence, turning away from him – though he heard the tears in her voice when she spoke again. “I’m very sorry Chris – but I think you’ll have to find some place of your own. The sooner the better.”

She told Millie that she wouldn’t see her father for a while, he was going away. But the little girl cried desperately that last time as if she couldn’t stop. Chris could not forget those sounds, the hiccupping, choking sobs and then the hopeless calling.

He’d hardly seen Millie since then.

—

Chris takes very little space these days, and it is becoming less; he doesn’t waste it. He slept in the car for a while, but the windows were soon broken, and he left it where it was. After a few weeks it disappeared. He slept for a few nights on a bench in the park, until it became too cold. Once, he slept on a bus. Now, it is a doorway.

—

Slowly, Millie unwrapped all the paper and opened the big box. What could the present be?

Inside the box there was a beautiful pair of wellington boots, with stripes in all the bright rainbow colours, and just exactly her size! The box said that the boots were magic, but no-one understood why, except Uncle Cuthbert, and he wouldn’t say. After their Christmas lunch they all went out for a walk, and Millie wore the boots straight away because it was very wet and soggy in the wood near their house. It was cloudy and dull, the trees were bare, there were hardly any animals, no birds…

“Oh, I just wish there was something interesting to see around here!” she said to herself.

Then, suddenly, a most wonderful thing happened! It had grown quite dark, but there was silvery moonlight all around, and deep in the wood, Millie saw a lovely unicorn, purest white. Slowly, slowly, she came right out into a clearing, treading softly,and Millie could almost touch the silvery-white mane. And she thought it would be nice to climb on the unicorn’s back and ride with her through the wood and see magic castles and beautiful princesses, and many other wonderful things. She reached out her hand…

“Millie? Millie, where are you? We must go home now!” Mummy called, from somewhere else in the wood.

And everything was gone, all at once, in that second…

Millie wondered if she had just imagined it all. But there was a patch of silver beneath the trees where the unicorn had stood – or maybe it was just a little piece of moonlight that was left behind there.

—

Once upon a time was the past, his thoughts of home, and warmth, family, work; his plans for a future that wouldn’t really be too different – promotion, another child, a new house one day. He is almost forty now. He’d married late, not sure even that it would ever happen for him. He’d had a broken childhood, difficult years, and later, a few false starts; but Emma, then Millie, had changed that. And now everything was gone, all at once…

Autumn seems long ago to him too – the sky and the trees like gold in the mornings, the early frost silver, as if the world’s wealth lay before him. He’d hardly noticed those things then; he remembers them now. That was a form of magic too, maybe.

There is only grey damp and chill around him these days.

—

It is the women he sees here on the streets near to him who are the most pitiful. One has greasy dark hair, red skin, roughened and coarsened – she is like an old crumbling brick. There’s a young girl who rocks back and forth, her eyes blank. There are other men too; he knows that many of them drink, some take drugs at night – he knows the signs, the smells. He thinks about the hidden stories, pushed down like his own beneath the heavy weight of humiliation and failure, pride and guilt.

They glance towards each other, but quickly, furtively, assessingly; they avoid each other’s eyes. They only see themselves there, their eyes are mirrors.

In a shop window, a different mirror, Chris sees another man, his red-brown hair long and dark with dirt, an untidy beard; at first he doesn’t know who the man is, doesn’t recognise him.

—

A few pages of the little volume are almost torn out, a few are marked by Millie’s fingers, or by drops of juice or milk. He’d enjoyed working out the story – it was not so different from many others that he and Emma had read to her, of course, but the drawings and sketches he’d done himself. They’d been a little rough, but Millie had loved them. There were pictures of the family, of Granny and Grandpa, all of Millie’s life that was important. His office colleague, Jen, in the Print Department, had helped him put it all together.

Some of Millie’s own scribbles and drawings are there too, in the margins, or at the bottom of the pages. The book has her scent, the scent of a child – sweet and soft, creams and powder and bubble baths. Or perhaps that is just his memory, or his imagination.

—

A few of the public are generous as they pass, digging into their pockets or bags and handing out a few coins, with a few generous words to match: “There you go, mate. Take care now.” Once, he was handed a pair of gloves when it was raining and his fingers were cold and numb as they received the coins: “Better have these too, mate!” Another time, he found an old plastic mac left in his doorway, and he wondered who might have left it.

But other passers-by wear an embarrassed half-smile and hurry on: “Sorry” – and a quick shake of the head. Some avoid meeting his eye, while scanning the cardboard, the dirty blanket, the plastic bags, their faces disapproving or disgusted. Others skirt round him completely, looking straight ahead, or they cross the road, walking more quickly. Some, the worst, are aggressive: insulting, swearing or spitting. There was a gang of lads one evening, drunk, vicious, kicking and jeering. Chris is tall and fairly strong, and he managed to get rid of them: ways and means. He doesn’t drink so much now. He defends his territory.

A woman and her daughter walk by one day, and Chris recognises them – the little girl is a friend of Millie’s. She stares, pulling at her mother’s sleeve. The woman glances at him, then looks again sideways, sharply, not quite believing. She catches hold of the child, mutters something to her and hurries her quickly by. That is worse than anything she could have said, any insult; worse than a kick, worse than vomit.

—

“You have it, Daddy!” Millie said when he left. “I won’t need it any more, I’m much too big for it now! I want you to have it so you’ll think about me while you are away!” Emma tried to take the little book from her, but Millie was determined. She ran towards her father, her coppery hair wild; she pushed herself close, found his hands and folded them around the book. Then she rushed back into the house again, crying, banged the door shut.

Chris puts the volume under his head at night, between the old newspapers. The makeshift pillow is a little softer then. The words and pictures steal out from the pages and enter his mind; the child there tells her own stories to him and they become part of his thoughts and his dreams and help him to sleep.

In his bag, in the daytime, it is all that he has, and more real to him now than anything else– his memories of his child, the magical stories and pictures that he wrote for her – though he’s not sure now how he managed to write them – his hope that he’ll be with her soon again, somehow.The words are like leaves, like colours, the colours of Millie’s hair: like riches.

—

Then all at once it was the end of the Christmas holidays. Millie went for a last walk along by the river with Granny, and she had to wear the new boots again because it was still very wet and soggy. The sky was grey, and there was nothing to see, only a man in a boat rowing by who waved to them and called Hello.