You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

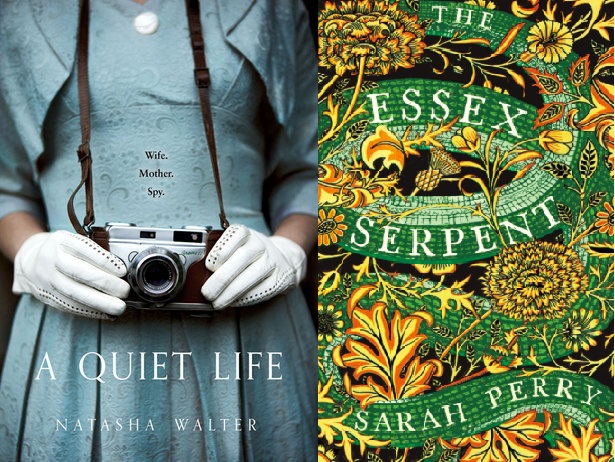

Two stylish feminist heroines, two chunky 400-page literary historical novels, both published on the same day. What’s not to like? Very little, actually. The fact that one of these books – A Quiet Life – is the debut novel from seasoned polemicist and journalist Natasha Walter makes the prospect all the more appealing. Most first-timers easing their way into the treacherous shallows of literary fiction keep book number one safely autobiographical, following the tired injunction to ‘write about what you know’. Not so Walter, whose richly imagined novel is loosely based on the life of Melinda Marling, wife of the Cold War Soviet spy, Donald Maclean. As a performance, it’s as solid as any from a veteran of ten books. Equally impressive is The Essex Serpent, the second novel by Sarah Perry, a book now riding high on the Sunday Times bestseller chart, and surely destined for adaptation in the BBC’s Sunday night cocoa slot. Which is not to say it’s cosy hokum dressed up in period costume – the book is bursting with subversive ideas and sly postmodern winks, almost too many for its propulsive plot to carry.

Oscillating between the fictional Essex village of Aldwinter and the sulphurous fin-de-siecle streets of London, The Essex Serpent tells the story of newly widowed Cora Seaborne and her involvement with Aldwinter’s young rector, the reverend William Ransome. Along with this moral beacon, she encounters his consumptive wife, Stella, and their children too. Cora arrives in the village relieved to be free of her late, controlling husband, accompanied by her savant son, Francis, and nanny, Martha. There she finds the population gripped by nocturnal terror. The mythical 17th-century scourge of the marshes, the Essex Serpent, has returned, apparently claiming fresh lives. With her keen (and fashionable) interest in geology, and the theories of Darwin and Lyell, Cora is intrigued. Could this fearsome winged beast, sighted in the opaque sludge of Blackwater Estuary, be the last of an undiscovered species? A living Ichthyosaur?

Into these murky waters is thrown emotional entanglement in the form of brilliant London surgeon, Luke Garrett (uncharitably nicknamed The Imp by Cora), and Cora’s new confidante, Stella Ransome, whose physical and mental disintegration steps up as the Serpent’s threat intensifies, and her husband is drawn inexorably to Cora. Of course, a community in fear from an external menace, with only religion and brute force to battle it, is one of the oldest and most potent plots. In Beowulf, a tale which Perry’s novel echoes, the local mere is haunted by Grendel’s mother; an emasculatrix inimical to the male world of the Mead Hall. This tradition of gynophobia was still alive and well at the end of the 19th century. The blood-sucking female vampires of Dracula are symbolic of late-Victorian England’s fear that newly emancipated women would undermine the hearthside wife. Perry opts for the something equally potent, but employs a cunning feminist inversion: Aldwinter’s nemesis is undeniably phallic. Here, it’s the serpentine interloper into Eden, corrupting all in its path – along with its analogue, the priapic, strutting, colonial male – that has to be neutralised in order for harmony to reign. With the book set as the British Empire begins its long decline, with Christianity in retreat, Perry’s White Worm gains much in symbolic resonance.

Along the way, the novel thoroughly explores all the binary oppositions of the 1890s. Superstition versus science, medicine versus ritual, female subjection versus male power, rural pastoral versus London squalor. All with a lightness of touch that crucially admits to retrospective knowledge. We’re never allowed to forget that these characters are preserved in the amber of history. Unlike the Victorian novels it occasionally pastiches, Perry has the benefit of writing from hindsight, adding an unexpected layer of pathos and comedy to the whole enterprise. Rather than the epics of Dickens and Wilkie Collins, the novel The Essex Serpent most resembles is Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman; and not just because both share a single, explosive erotic encounter, all the more powerful for never being repeated. Yet in the end, it’s Perry’s soaring descriptions of the natural world – her faultless and haunting evocations of the Essex marshes – that linger the most. In this respect, the book could belong to the tradition of English Eerie, to be found in stories such as Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Willows’. The following passage might almost come from its pages:

On turns the tilted world, and the starry hunter walks the Essex sky with his old dog at his heels . . . On Aldwinter Common the oaks shine copper in the sunblast; the hedgerows are scarlet with berries. The swallows have gone, but down on the saltings swans menace dogs and children in the creeks.

Natasha Walter’s A Quiet Life doesn’t employ such lyrical touches, but then the grey postwar world of espionage where the book is set argues against embellishment. In contrast, her prose is smooth yet without adornment; an engine that rolls her engrossing plot forward without drawing attention to itself.

When the independent yet unworldly Laura Leverett arrives in England on the ferry from the States in 1939, she encounters much in the way of culture shock. Though she straddles two worlds already, with an American father and an upper-class English mother, her eyes are opened on the journey over by young communist firebrand Florence Blake, and by her torrid encounters with a debonair journalist. Both liaisons continue in wartime London, where Laura is staying with her snobbish aunt in north London. When not exploring her awakening political conscience at Marxist meetings with Florence, she’s drawn into the circle of young Whitehall civil servants. There she meets Edward Last, ostensibly a dashing, poetry-quoting Hugh Grant of the dusty corridors of power, but in reality a Soviet agent leading a precarious double-life.

Thus Laura plunges into the world of dead-letter-box espionage, with covert meetings in hotels, and rolls of film passed under newspapers on Hampstead Heath benches. The books really takes off in the section that describes London life under the Blitz, with the ever-present ‘thrumming of planes’, and faces ‘lit by the green-white flares of the incendiaries bursting on the road’. Against this background of war, and ‘denunciation and counter-denunciation’, the action moves to Washington, and finally to Geneva after Edward is exposed as a traitor and defects to the Soviet Union, leaving Laura carrying their child. Stripped of her dignity, Laura then tries to piece the fragments of her life together.

While Greeneland such as this might seem an unexpected milieu for the trailblazing author of The New Feminism and Living Dolls to be operating in, it makes sense when looked at in terms of how women were expected to behave in the repressive 40s and 50s. Just as The Essex Serpent exposes the male world of the 1890s to retrospective ridicule, the feminism in A Quiet Life is an unobtrusive undercarriage that holds the unchallenged patriarchal views of postwar Britain and America up to the light. The book’s coup is to show how the concealment necessary for spying is congruent with the concealment a woman must employ if she is to get through life unchallenged. This covers everything from menstruation (observed unflinchingly, as Doris Lessing did The Golden Notebook), to stillbirth, or even the voicing of opinions that might ruffle male feathers. Indeed, the book is relentlessly somatic, from its explicit descriptions of female desire, to a slowly healing Caesarean scar, which fills Laura’s days with ‘a current of physical pain’.

By the book’s end, one is left with the feeling that Walter is a natural when it comes to fiction. While the prose is not as baroque as Perry’s, it is filled with tightly observed details that nail whatever her eye falls upon; from the ‘tough little chops’ on the ferry over to London, to the ‘scurrying maid’ of an aristocratic traveller, to the ‘trees and their yearning reflections in the water’ in a Washington park. Deftly handling character, narrative and mise-en-scene, while seamlessly integrating issues of gender, class and postwar politics, A Quiet Life is an immersive, memorable debut.

About Jude Cook

Jude Cook lives in London and studied English literature at UCL. His first novel, BYRON EASY, was published by William Heinemann of Random House in February of 2013. He has written for the Guardian, the Spectator, Literary Review and the TLS. His essays and short fiction have appeared in Litro, Structo, Long Story Short and Staple magazine.

“he book is bursting with subversive ideas and sly postmodern winks, almost too many for its propulsive plot to carry.”

I’m trying to find those postmodern winks but I have been unsuccessful so far. Any guidance here would be much appreciated!