You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingA Book with the Sound of Its Own Making Covered with Semen…

You’d expect a book that was inspired by the ten tracks on Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures to contain some green and greasy semen somewhere along the line. And this book does not disappoint. From the final fiction, “I Remember Nothing”, by Anne Billson: “I look forward to tasting his green greasy semen again, and laughing with delight, remembering how earlier I found it so repulsive. What a fool I was. It’s a delicacy.”

A metaphor for JD’s music and the whole spectrum of post-punk? At first you’re not too sure, it sounds dodgy, but then, gimme gimme gimme. Dribble, dribble, dribble down chin. They were probably right naming the album Unknown Pleasures though, rather than the more jazzy Green and Greasy Semen.

It will be forty years in 2019 since the release of this seminal album that’s forever intertwined with the suicide of Ian Curtis in 1980. A suicide like a black blanket permanently wrapping this record. But not by Christo. Thus, most people just won’t go there. It’s like handing someone a frothing pint of green and greasy semen and asking them to pay thirty quid for the privilege of drinking it down in one gulp. Eh, no thanks there mate.

All this misjudged levity is really an attempt to sublimate the subject matter of the record that inspired this collection: depression. As Mark Fisher said, Ian Curtis goes way beyond the blues and into the pure, unadulterated black. This is the black dog fully grown, ungroomed and drooling all your serotonin onto the floor. Go on, try to lick it up. See what I fucking do. Make my day, punk. And besides, as Camus said, “After all, the best way of talking about something you love is to speak of it lightly.”

It’s 1979 and Thatcher is here to change everything irrevocably. There’s nothing more for the young working class to look forward to anymore, except make two modernist masterpieces and kill yourself. And the first fiction in this collection, “Disorder”, by Nicholas Royle, paints a frightening montage of those times from inside the mind of Ian Curtis. “The pain is here. Mine.” The words of this fiction comprise all the lyrics from the album. No quotation is used and “no word is repeated unless it is repeated in the lyrics.” A mad scientist of a Sudoku puzzle yet quite chilling because even when the words are all mixed up and put into another narrative, the message stays the same. Life is a pantomime. It’s shit. Don’t take part. Kill yourself. “I’ve lost the means to connect, the will to know the truth.”

There’s a conceptual artwork by Robert Morris from 1968 called, Box with the Sound of Its Own Making. The artist recorded himself making a wooden box. Then he slapped said box onto a plinth in an art gallery and played the recording of the sound of its own making as a soundtrack, thus pricking the romantic balloons of the art-mystics and drawing attention to the actual boring and time-consuming nature of making art. This collection could be called Book with the Sound of Its Own Making or perhaps more a propos, Coffin with the Sound of Its Own Making, for the cut-up lyrics in this first fiction get so raw you can physically see bones sticking out from skin: “Descend by wire with my own hand”, and, “I’ve talked for too long. But I’ve said it all. I have to live until there are no new sensations anymore”. This will leave you, “Occupied by death. Corrupted by sin”. Which I suppose was the original intention of the album. If you cut-up the words you use in a week and rearrange them into a different narrative, would the same hold true? You’d get the full picture of what you’re actually thinking and feeling without the blinkers, would you? With modern technology it’s certainly doable to record everything you say for a week. But would you really want to go there? Really? To know yourself that well? But then we all know ourselves only too well, and need constant distraction in order not to say it as out-loud and as out-straight as Ian Curtis’ lyrics and the sound made by the rest of the band. This album and this particular fiction is the be-here-now moment we don’t want to know about. Because in the next fiction, “Day of the Lords”, by Jenn Ashworth, the be-here-now moment is the up and coming world war with Russia. It doesn’t say it’s Russia. I just know it is. And who the hell wants to focus and think about such a reality in the ice-cold manner of a JD track? That much death? Not me. So it’s best to focus on (in this story) the broken relationship of a couple with a young child instead. The mother’s new partner has to deliver the child to his father on one of his weekly Saturday access visits, while conscription, mind-altering drugs and bad dreams by father and son quietly explode in the background. So a good interpretation of the JD track it was inspired from, but perhaps a little bit too literal. A delicate, beautiful at times, telling of this four-way relationship, punctuated by nice lyrical squawks along the way: “He was zipped up in a tight red raincoat, the laces of his shoes done up in big bows.” But it’s all, as I said, a distraction from the war raging in the background and the gradual degeneration of the human psyche, only delaying the ineluctable march of death. Listen to JD. Go on, kill yourself. Cut out the middle man. Don’t just wait cowardly for the Russians and the Americans to press the nuclear buttons. Rick, the soldier father of his young son, Ted, says, “Distracting him out of a tantrum. He once threw a fit in a supermarket and I told him there was a pigeon sitting up on one of the shelves and he was scaring it. It kept him entertained for an hour, that one did.” A fizzing ice-cream in lemonade of an image in sharp contrast to “Candidate”, by Jessie Greengrass. This is pure Joy Division. No quarter given. Like a noose around your neck. But in a good way because as your legs are dangling there in midair, it can feel like you’re dancing. And we all love to skank. Of course we do. Again, attempted levity to distract from a real and fictional world of zero-hours contracts, unaffordable housing and constant it’s-so-easy-to-be-an-entrepreneur courses shoved into your face as soon as you open your mouth to breathe. It’s grim out there. And so too in Jessie Greengrass’ story: “We have always lived in the factory. We were born here amongst the engines and the lathes, the conveyor belts which stretch for miles.” It has everything, that opening sentence. The history of Manchester pigeon-struts up your nostrils. Frederick Engels, Peterloo, Thomas De Quincey, Cottonopolis, Sex Pistols in the Lesser Free Trade Hall, Tony Wilson’s Factory Records, The Fall, The Smiths, The Hacienda, etc. It’s not supposed to be a comprehensive list.

This story reminds me of Bernard Sumner’s experience of the shock of real life, that Mark Fisher wrote about. He grew up in Salford in a two-up two-down. An idyllic childhood relatively speaking, poor but with ample opportunity to play on the street to all hours. Long games of Giant-Steps-Baby-Steps with all his mates. On summer evenings even the mothers, fathers, grandparents and grandmothers would be up chatting outside at their front doors until past midnight sometimes. But the factory wouldn’t allow that. The houses/slums were pulled down and everyone was flicked into tower blocks with all its attendant anomie. The shock of real life. “We don’t know what it is we make. We don’t know the purpose of so many narrow lives. We only know the way to slot this piece to that one.”

Back then the culture of the times created people as inveterate modernists who would spit into your earholes if you asked them to repeat something from music’s past. It just wasn’t in their nature. Progression was the carrot that made them hopeful. Mark Fisher again. He said everything. Greengrass says, “A necessary recalibration of a mechanism. A swift repair. Hope is a lubricant.” Yet this story shows that even creating two astonishing works of art doesn’t prevent the dead-certain future from putting that noose around your neck.

“Insight”, by David Gaffney, seems to refer back to Robert Morris’ Box with the Sound of Its Own Making. Or Coffin with the Sound of Its Own Making. A man buys Ian Curtis’ former house in Macclesfield and one of his new neighbours offers him big money to buy the garage that comes with the house. The why and the wherefore of his interest in acquiring the garage will definitely put a chill down your trousers and leave you thinking for days afterwards. So a decent cover of the JD song that doesn’t spare the maggots.

Sophie Mackintosh’s (on the longlist for this year’s Booker Prize) “New Dawn Fades” gets even deeper into Ian Curtis’ mindset as the protagonist is haunted by her past self. Today, yesterday seems nostalgic. You hated yourself and could barely look up from staring at your shoes back then before finally being pushed outside into the natural light. Those sad and anxious days of yore seem rosy and practically carefree compared to today’s trials and tribulations. You want to go back. You can’t go back. You want to go back. Even though you wanted to kill yourself back then like you want to kill yourself now. Sophia Mackintosh writes, “A place will disappoint you like a person. No more pearlescent lustre. No more pastel water.” This is intense fiction with scant narrative detail, making you fill in a lot of the gaps yourself. The world within this fiction inexorably leads you to a room with a gun and a locked door and then a loud bang: “Spreading you and your feelings around like butter on toast, diluting the intensity of your territories.” My interpretation. Is this the only way of obliterating the intensity of where you were born and raised? Possibly. Another decent attempt at a JD cover version.

“Transmission, A Graphic Interlude”, by Zoe McClean is imaginatively drawn and a quick, lively read. Minimalist with word and line. An Ian Curtis-esque live transmission. Making me think of JC. Jeremy Corbyn is a racist and an anti-Semite, apparently. The surf is sky high. No wonder Ian Curtis ended it the way he did and didn’t live to see such duplicity. But Ian was a Tory apparently and always voted that way according to Deborah Curtis in Touching from a Distance. So there’s Krautrock-like electronic interference coming through in this particularly enjoyable graphic interlude.

“She’s Lost Control”, by Zoe Lambert is a darling of a story that interprets the lyrics of the song literally. A young woman of nineteen. Her epilepsy manifests at the worst time of her life, if there’s ever a good time to be diagnosed with anything. “It happened just as her friends were starting to cut their hair into long sexy fringes and watch bands in Manchester, just as they were getting jobs or going to college or getting married. She found her life getting smaller.”

“Shadowplay”, by Toby Litt is a Philip K. Dickish fiction and is not only a cover-version of JD’s Shadowplay but also a cover version of Martin Hannett’s contribution to the album. A story about a very rich man that’s paid big bucks to transfer himself into another body so he can live again. After an accident / robbery / kidnapping involving seven robot Prousts the protagonist finds himself in a spaceship millions of miles from where he’s supposed to be – and alone. The ship has a personality and a voice. You can turn everything on and off. “But he could tell it was an interference and he asked to get rid of the pleasure. It did.” The ship can make things in life more enjoyable and keep your senses high as a constant injection of heroin. It must be like what being middle-class feels like. But he wanted it turned off. He was alone and wanted to feel alone. What was the point in simulating anything else? If it’s ice cold and lonely, with no one else to talk to, except programmed robots, then why pretend otherwise? During the recording of the album Martin Hannett use to turn off the heating in the studio to drive all the members of JD to the pub so he could do what he wanted to their sound. So I see the protagonist in this story as Martin Hannett building a new graveyard from the already masterpiece-like work presented to him by JD. Gilding the lily. A coffin with the sound of its own making.

And further into the freezer we go with “Wilderness”, by Eley Williams. A story about a person who works as an ice-resurfacer. Dancing on ice and all that Olympic sportiness in tassels. The language employed here is quite seductive: “…give me the calming scrape and top of my mechanised strigil, the pizzicato of my re-surfacer across the ice, and I’m completed transported.” It makes me want to jump into the rink after all the dancing on trippy tippy toes is over and lie down on the ice looking up at the roof with crossed arms like Dracula in his coffin. Waiting for the protagonist’s ice-resurfacer to come toward me, and poetically, do the business. Put me away. Rebuff and gloss me over into the ice. “I’ve developed an ear for the phonology of ice-resurfacing, the word itself almost onomatopoeic, and catch myself listening out for the fricatives of the blades on ice.” A mellifluous, sensuous and life-affirming annihilation. JD present no answers, however forward-looking their sound. They present the unvarnished truth in all its poetic blackness. If you can banish hope without killing yourself then rave on. And we’ll all live happily ever after. The ice-resurfacer in this story only wants to help and connect with people however difficult his personality. But without hope, there is hope after all: “A cut-up ice rink is something lacerated but unweeping, furrowed like a brow but unthinking, ploughed but not bringing anything to harvest.” Scary but then again, not so scary.

“Interzone”, by Louise Marr, shows how all the progressive dreams of the past were shot dead in their tracks by Thatcher and her confrères. A young woman gets a job as a Project Manager and has to attend a high-fallutin meeting with all the design and architectonic bigwigs of the company. She’s fully qualified for the job but had been working in a coffee shop for a long time previously. At the meeting they discuss, question and show slide shows and drawings from the past. “From around the world, there were pictures of bridges to nowhere and highways that just ended, paving and tarmac coming to an abrupt end on the bare earth.” Sound familiar? Constructions just left hanging in midair forever frozen. There’s no way back to build forward from where things were left off no matter how many meetings.

And finally, “I Remember Nothing” by Anne Billson is pure horror show. A man and a woman wake up in bed together covered in green greasy semen in a room neither of them recognise. They don’t even remember who they are. When they finally do realise, make sure you read these paragraphs again and again. Ian Curtis’ makes the case for the base nature of man over and over in his lyrics, like this final story in the collection. The phrase the base nature of man brings immediately to mind, Nazis and fascists. JD were accused of being fascists themselves in their overly fond use of Nazi references. Were they Nazis? I personally don’t think so.

Rik Mayall in The Young Ones (Rick with a silent P) used to casually call everyone who gave him the hump a Nazi or a fascist. And when I was young, many people I knew did the same. Like crop rotation in the seventeenth century, it was more widespread. Hold on. Considerably more widespread. These references outside the context of history lessons in school I found quite exhilarating. Yes, a bit childish and Kevin-and-Perryist. But not entirely wrong. Were they? I must have been stupid because when people compared someone to a fascist it made me feel intelligent (I was very young) that I got the reference and saw the comparison. Although I knew to take it as an exaggeration. But the past is a different country, I suppose and maybe I’m wrong. Everybody’s clever nowadays apparently. You’re not supposed to bring the Nazis into anything anymore, it would appear. The trope goes that the first person to invoke the Nazis or fascists loses the argument. And is this the final horror of all horrors that this story is trying to scream? That JD are fascists. Which means by implication that all the writers of this book are fascists? Which makes me one too for reading it. Perhaps not. But worth considering when you’ve finished this death-rattling good read.

Before the horror of all horrors (from “I Remember Nothing”): “Rancid and noxious and green, like no semen I’ve ever encountered, and I’ve encountered quite a lot of it, in my time.”

After the horror of all horrors (from same story): “I look forward to tasting his green greasy semen again, and laughing with delight, remembering how earlier I found it so repulsive. What a fool I was. It’s a delicacy.”

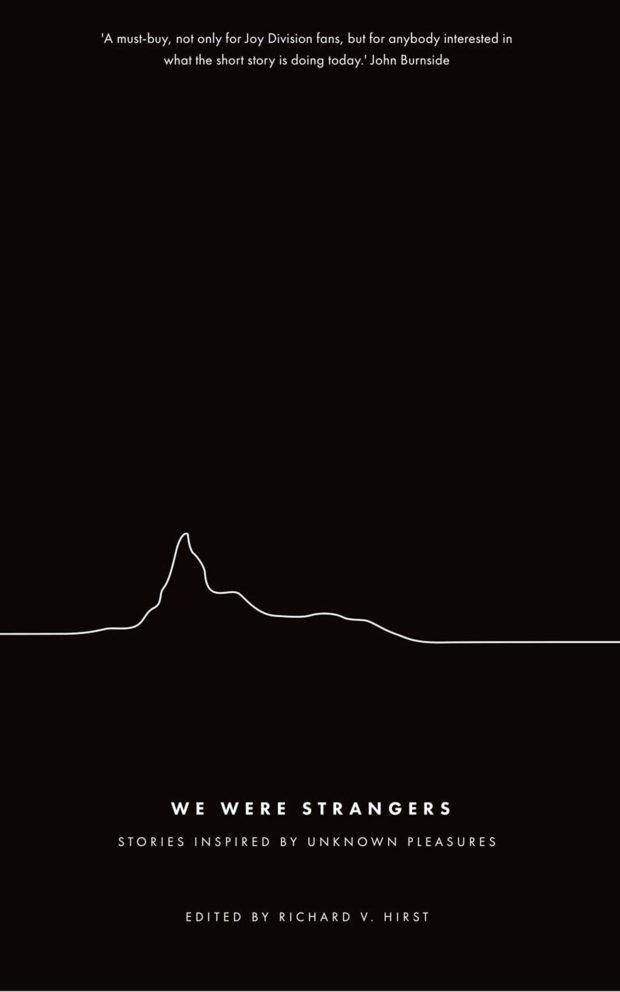

We Were Strangers is out now from Cōnfingō Publishing.

About Camillus John

Camillus John was bored and braised in Dublin. He has had writing published in The Stinging Fly, RTÉ Ten, The Lonely Crowd and other such organs. You may know him from such fiction as The Woman Who Shagged Christmas, The Rise and Fall of Cinderella’s Left Testicle and, Throwing A Sausage Back and Forth for Five Minutes Without Letting it Drop. His fictionbook, Groin Frosties With Jazzy Hand – The Pervert’s Guide To Modern Fiction, and his poembook, Why The Privileged Need to Read Literature, are available to purchase from Amazon. He would also like to mention that Pats won the FAI cup in 2014 after 52 miserable years of not winning it.

Nice Article.

Nice Article!