You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingFictional Cults Lack Verisimilitude

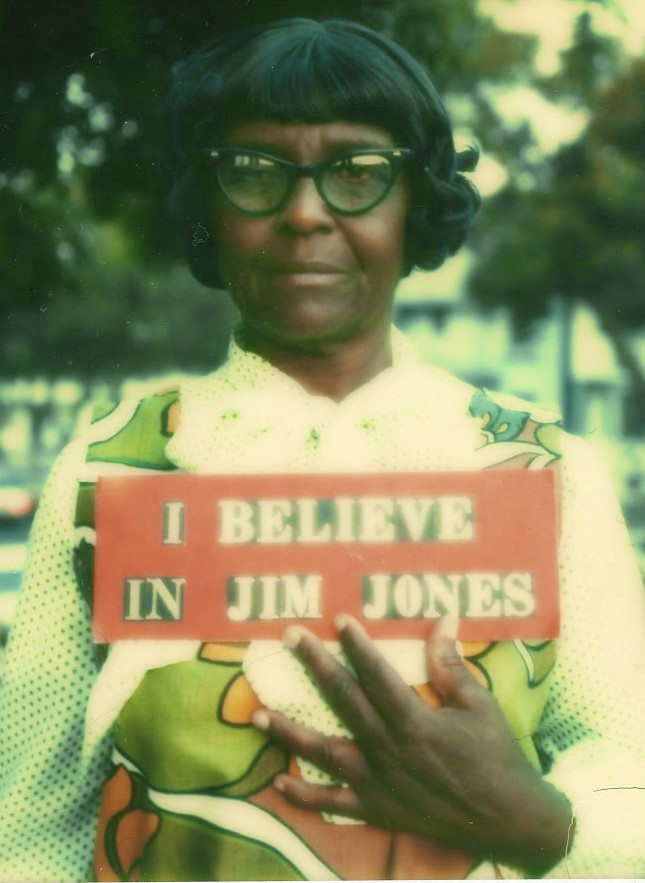

Charlie Manson and his “family” provide the historical backdrop for Emma Cline’s first novel, The Girls, just published with a multimillion-dollar book deal for the white American author, born in 1989. Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple serve as real-life fodder for fiction published last year by Guyanese-Canadian Fred D’Aguiar (reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review) and a small press contribution by African-American Sikivu Hutchinson, White Nights, Black Paradise. Why do cults so fascinate the reading public, and why, when actual history begs one’s imagination with its rawness, does fiction carry such great weight in their portrayal?

Charlie Manson and his “family” provide the historical backdrop for Emma Cline’s first novel, The Girls, just published with a multimillion-dollar book deal for the white American author, born in 1989. Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple serve as real-life fodder for fiction published last year by Guyanese-Canadian Fred D’Aguiar (reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review) and a small press contribution by African-American Sikivu Hutchinson, White Nights, Black Paradise. Why do cults so fascinate the reading public, and why, when actual history begs one’s imagination with its rawness, does fiction carry such great weight in their portrayal?

In Cline’s new offering, the first-person protagonist offers the inside story of a 14-year-old girl in the late 1960s drawn to a charismatic older man, Russell, who plays bad guitar and attracts females like flies to offal, groups of them clustering in his wake. Cline also imparts the perspective of age, if not wisdom, as the contemporary story unfolds, a 50-something Evie looking back at her adolescence when confronted by unexpected young guests, including a teenaged girl who recalls her former self, in thrall to a bad boy/man.

The Evie we meet on the first page is white, from money, bored at the beginning of a Northern California summer, lonely and more or less ignored by recently divorced parents, both of them with new partners, desperately seeking personal ful-fillment while their only child languishes with too much freedom and zero responsibilities. The fictional Evie, who has no counterpart in the Manson story, allows the reader to pry inside the mind of an impressionable female who just might go so far as to join in a brutal mass killing; then again, she might not.

All three novels have in common the desire to understand what the facts don’t sufficiently explain. In Manson’s story, well-heeled, intelligent females carve Xs in their foreheads and murder strangers for the man they worship. With the followers of Jim Jones, nearly 1,000 United States citizens – a racially mixed group one third elderly and another third children – either commit suicide voluntarily or are forced into ingesting poison in a Guyanese jungle. Countless non-fiction books — covering genres from religious history to sociology to psychology and more – recount “what really happened” and attempt to impose order on the chaotic, murderous behaviour of groups of twentieth century Americans. But “the truth” fails to satisfy.

Cline’s version, written in lucid, shining prose, allows us to inhabit the skin of a mostly passive teenager, dabbling in drugs and drink and wondering if sex will bring her into the adulthood she thinks she craves. Unfortunately, the first-person narrative, while most immediate of all points-of-view in fiction, works less well if the reader chafes inside that particular character’s skin.

As a child, I had once been part of a charity dog show and paraded around a pretty collie on a leash, a silk bandanna around its neck. How thrilled I’d been at the sanctioned performance: the way I went up to strangers and let them admire the dog, my smile as indulgent and constant as a salesgirl’s, and how vacant I’d felt when it was over, when no one needed to look at me anymore.

The above is the elder Evie reflecting on her childhood in a curious blend of nostalgia and angst. We don’t actually meet the grown up Evie until Part Two begins, 131 pages into the story. However, Evie’s wistfulness persists whether she is 54 or 14; she never got what she was looking for, it seems, and a melancholy passivity suffused the entire novel.

Further reflecting on that girl with the dog, Evie muses:

I waited to be told what was good about me. I wondered later if this was why there were so many more women than men at the ranch. All that time I had spent readying myself, the articles that taught me life was really just a waiting room until somebody noticed you – the boys had spent that time becoming themselves.

Waiting, in fact, is what Evie does most and what she does best. For readers impatient with such inertia, Evie’s tale, though always beautifully written, sinks into its lassitude.

Children of Paradise, the first novel published in the United States to deal with Jones and Jonestown, launches itself into magical realism as it makes one of the key protagonists a gorilla, Adam, based on the chimpanzee Jones kept caged in the jungle. D’Aguiar speaks from the animal’s perspective, attempting to give the reader an entirely “other” perception of Jones and his mania. The two female characters, an African-American mother and daughter who bravely make the best of an impossible situation, where they are always hungry and fearful of the leader’s mood swings, allow us some insight into the ineffable. Two human beings who love one another, bear the burden of hope, though we suspect their story will not end well, as we know the brutal revelations of Nov. 18, 1978, the 900+ bodies bloating beneath the equatorial sun.

Of the three novels, it is the relatively unknown scholar of secular social justice Sikivu Hutchinson who manages best to present a simulacrum of life as it might have been in the jungle compound of Jonestown. Jones’s eponymously named village began in 1973 as Eden-in-exile, the Utopian strain of American history this time intertwined with the goal of ending racism, making an egalitarian paradise anew, forging a New World out of the jungle.

Of course, it didn’t happen like that. The inner circle of Jones’s administrators is all white, with occasional black token figures. Jones, like Manson, had a predilection for sex with multiple partners, all white with one exception. Unlike Manson, Jones included men in his conquests, many of whom returned his favours with undying loyalty, including the Jewish doctor who mixed the cyanide-Flavour Aid concoction (not Kool Aid, as the phrase has come down to us in popular parlance).

Protagonist Taryn, who embodies the role of skeptic and seer, laments:

We’re the only ones dumb enough to leave the States en masse without a plan for a way back. In fact the government is probably saying to Jim, why can’t you take some more Negroes with you? While you’re at it, take all the ghettoes of Watts, Newark, Detroit and Harlem and dump them in Jonestown. What the fuck do we care about a bunch of spooks.

Perhaps Hutchinson’s novel carries more heft as a fictional depiction of an historical tragedy because her characters are stakeholders, invested and doomed, not passive onlookers. D’Aguiar’s characters are similarly involved, though the trope of the anthropomorphic Adam makes for difficult reading, the suspension of disbelief not possible. While Cline purposely chose a protagonist who did not participate in the fictional version of the Tate-La Bianca murders, her choice of leading character lent an air of avoidance rather than engagement with the grit and horror of the original story.

About Annie Dawid

Annie Dawid is the author of three books of fiction: YORK FERRY, a novel. Cane Hill Press, NY 1993 LILY IN THE DESERT: STORIES, Carnegie-Mellon University Press, 2001 AND DARKNESS WAS UNDER HIS FEET: STORIES OF A FAMILY, Litchfield Review Press, Short Story Prize, 2008

The first novel published in the United States to deal with Jones and Jonestown launches itself into magical realism as it makes one of the key protagonists a gorilla, Adam, based on the chimpanzee Jones kept caged in the jungle. D’Aguiar speaks from the animal’s perspective, attempting to give the reader an entirely “other” perception of Jones and his mania. The two female characters, an African-American mother, and daughter who bravely make the best of an impossible situation, where they are always hungry and fearful of the leader’s mood swings, allow us some insight into the ineffable. Two human beings who love one another, bear the burden of hope, though we suspect their story will not end well, as we know the brutal revelations of Nov. 18, 1978, the 900+ bodies bloating beneath the equatorial sun.

nice!!