You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

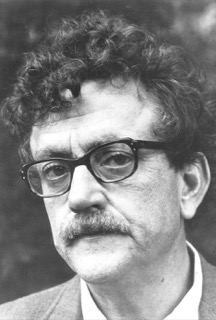

Go shoppingAccording to the Oxford English dictionary, the semicolon is “a punctuation-mark consisting of a dot placed above a comma (;). In present use it is the chief stop intermediate in value between the comma and the full stop; usually separating sentences the latter of which limits the former, or marking off a series of sentences or clauses of co-ordinate value.” This unobjectionable definition, written in neutral, taxonomic language and comically literal at the start, does little to indicate the semicolon’s surprisingly contentious status. While hatred of the semicolon is no modern phenomenon –as far back as 1647 English writer Ben Jonson called them a mark of an “Imperfect sentence”– no other writer voices as vehement and vitriolic a hatred of the semicolon as the twentieth century American writer Kurt Vonnegut. Speaking to his creative writing students, he once (in)famously laid down this commandment: “First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college.”

While not all writers resort to such overt slurs to malign the seemingly innocuous punctuation mark, Vonnegut’s statement condenses the fundamental criticisms of its enemies. His personification of semicolons as “transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing” accuses them of having no true ‘nature’ or ‘essence’ of their own; floating between the respectable and well-established comma and period, neither one nor the other, the semicolon is dangerously ambiguous. Rather than being a mark of sophisticated expression, it’s a stylistic deficiency, unnecessary and pretentious frippery that merely confuses, rather than aids, communication. George Orwell agreed when he said, in his characteristically committed, deadly serious fashion, “I had decided about this time that the semicolon is an unnecessary stop and that I would write my next book without one.”

What I find especially interesting about this comment, however, is not that Vonnegut criticizes the semicolon’s usefulness but that he says it exposes the classist pretensions of a writer who wants his readers to know he’s “been to college.” Vonnegut assumes that even the use of this simple punctuation mark, one of the smallest units in the network of language, is capable of revealing a writer’s political and social self. At the time he was writing, to question the connection between language and class consciousness was in vogue. In 1953, only two years after the publication of Vonnegut’s first book, Roland Barthes publishes Writing Degree Zero where he examines the cataclysmic moment writers realized that language wasn’t an innocent, transparent medium, but a worn tool that had historically served power and privilege. Vonnegut seems to avoid the semicolon not just for the sake of clear prose, but to reject this elitism, or perhaps as Barthes would put it, “to repudiate his bourgeois condition.” In a letter Vonnegut wrote to writer Richard Gehman, who was beginning a career as a university professor, Vonnegut does indeed embrace a certain ‘commonness,’ or being ‘of the people.’ He tells his old pupil to “forget his lack of credentials,” turns their lack of degrees–or being a “barbarian” as he calls it–into something to be proud of, and even suggests that this might be the mark of a “REAL WRITER.” If rejecting the semicolon becomes an anti-institutional, populist gesture in Vonnegut, for his fellow semicolon-hater Orwell it becomes a much more concrete expression of political commitment. Orwell writes clear, declarative prose–work of the pen aspiring to the potency of the sword–to fight totalitarianism, to defy the spurious language of fascism that uses ambiguity to “[conceal] or [prevent] thought.”

Of course Vonnegut’s statement is interesting, perhaps first and foremost, for the way it also throws gender into an already contentious discussion. Does the semicolon have a class? Does it have politics? And does it even have a gender? His off-color metaphoric language, far from being a problematic but simply coincidental choice of words, initiates him into a tradition of American male writers who reject the semicolon for its supposedly feminine quality. Cormac McCarthy said, “No semicolons,” calling them aberrant, “weird little marks,” while Ben MacIntyre says writers like “Hemingway and Chandler and Stephen King [similarly] wouldn’t be seen dead in a ditch with a semi-colon…Real men, goes the unwritten rule of American punctuation, don’t use semi-colons.” This questionable argument is unfortunately only helped by the fact Virginia Woolf, a writer who has been consecrated the ‘paradigmatic’ female writer, makes abundant use of the semicolon. Her novel Mrs. Dalloway contains over 1,000 of them. Vonnegut’s comment slightly differs from the traditional assumption that semicolons are feminine–they are a ‘problem’ for him because they fall into neither end of this gender binary–but like these other writers he wants to assign the semicolon a gender and even a sex. It’s funny that anything Vonnegut might say would remind me of the feminist writer Hélène Cixous–the two are practically antithetical humans–but they identify certain structures or forms of language with sexuality in bizarrely concrete ways. In her seminal essay “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Cixous exhorts women to write in a way that breaks free from the logical, linear, singularity of male, ‘phallocentric’ writing. She urges women to ‘write with their bodies,’ to write plural, many-meaning-ed texts that mimic the female body’s multiple erogenous zones.

If you’re surprised at where the semicolon has taken us, I am too. If you’re put off by this desire to give the semicolon an essentialist identity, whether that be elitist or fascist on the one hand, or female on the other, and find it a bit ridiculous, I am too. For this reason, I’ll end with a hilariously parodic quote from Gertrude Stein about semicolons: “They are more powerful more imposing more pretentious than a comma but they are a comma all the same. They really have within them deeply within them fundamentally within them the comma nature.” This quote is nothing if not tongue-in-cheek; claiming to know the ‘comma nature’ without putting any commas where they should be, the rule-breaking Stein makes play even of punctuation. I like to think she’s looking at me, winking ;) and saying hey, it’s how you, the individual writer, use the semicolon that makes or breaks it.

About Haley Stewart

Haley Stewart is from Portland, Oregon and a graduate of Williams College in Massachusetts. Currently, she's continuing her Comparative Literature studies at the University of Cambridge. She's a lover of prose and poetry alike, a fluent Spanish speaker, trying to learn French and an avid traveler.