You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

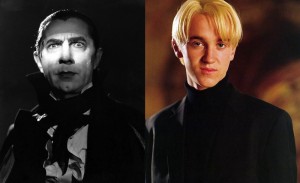

Have you ever been seduced by a downright villain? I know I have. From Satan to Sauron, Dracula to Draco Malfoy, literary miscreants have been stealing the limelight and beguiling the reader for centuries. Most of us are, however, honest, law-abiding citizens so why is it that we are repeatedly drawn to fiction’s bad boys? What is it about monstrosity that is so appealing? And will we ever resist the lure of the dark side?

The word monster is often associated today with villainy, innate evil and horrific wrong-doings but originally, the word can be derived from the Latin ‘monstrum’ meaning something marvellous. For me, this could be a clue behind our fascination with the dark side: villains are marvellous. Always partial to a touch of the dramatic, many literary villains are also showmen; committing horrible crimes, yes, but often in such an ingenious way you cannot help but admire them. As journalist and literary villain-aficionado Kim Newman outlined recently in an article for flavorwire.com: “To be a great villain, it’s not enough just to be thoroughly evil – you have to be entertaining with it. A certain panache helps, especially for villains who fall into the category of arch-nemesis and have to prove themselves almost the equal of a flamboyantly brilliant hero.” Consider a character like Arthur Conan Doyle’s Moriarty, the self-styled ‘Napoleon of crime’ and arch-enemy of Sherlock Holmes: only such a ruthless villain could match Holmes and also be, according to Doyle, behind every evil deed that goes undetected in London.

Ever since the Renaissance, fictional rogues have been using underhand, Machiavellian tactics to outwit and outshine their heroic counterparts. One only needs to explore a genre like Revenge Tragedy to find heinous crimes enacted in extraordinary ways, often culminating in a grisly, yet dramatic tableau of slain bodies in the final scenes. Gruesome, yes, but it certainly leaves an impression upon any audience or reader – although we may forget over time the hero’s various virtues, bad guys are always more memorable.

My favourite literary villain has to be Shakespeare’s Richard III. Crafty, manipulative, murderous and cruel, he’s the kind of character one ought to despise, but I know I’m not the only audience member who has ever felt a strange fascination with this monstrous man. Unlike good Clarence or the heroic Richmond, Richard connects with the audience – he speaks in asides, making you complicit in his evil plans and eager to see how they will unfold. Furthermore, it’s Richard that gets all the good lines – many of us can remember the famous “Now is the winter of our discontent” speech, but when it comes to the other characters, our minds go blank. To a certain extent an underdog: facing many obstacles in his pursuit of Kingship at the beginning of the play, the audience almost cannot resist rooting for him. Richard is compelling, dazzling and complex – I want to figure him out and understand what makes him tick. Trying to piece together the puzzle behind a literary villain’s malevolence is a challenge for many readers and the reason why scoundrels like Mrs Danvers in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca or Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels remain so irresistible.

So what was Shakespeare thinking when he made Richard so appealing, or indeed any author who creates an unforgettable villain that we love to hate? Often it happens that the bad guys have to be seductive in order that the reader, as well as one or more of the good guys, is lured into their web of darkness. If villainous characters were simply clear-cut evil wrong-doers, it would be difficult for a reader to understand why other characters in the book may be deceived by them. They can certainly charm the reader too. Without them, think how anaemic some books would be. Oliver Twist without Bill Sikes, for example? Forced to make a choice, I’m probably not alone in preferring the book without young Oliver himself.