You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingFor our Mystery theme, Thomas Chadwick revisits a postmodern classic in which the clues seem infinite and may mean everything … or nothing.

Chance n. … 3. An unexpected, random or unpredicted event.

Coincidence n. … 2. A sequence of events that although accidental seems to have been planned or arranged.

When Californian housewife Oedipa Mass, the principal character in Thomas Pynchon’s 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49, leaves Kinneret to make her way down to San Narciso to look over the ledger of one Pierce Inverarity (deceased) – a man with whom she had a brief relationship and who has designated her as the executor of his will, she tells her husband, Mucho Mass – a used car dealer turned radio disc jockey – to look after the oregano in their garden as it has contracted a strange mould.

When Californian housewife Oedipa Mass, the principal character in Thomas Pynchon’s 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49, leaves Kinneret to make her way down to San Narciso to look over the ledger of one Pierce Inverarity (deceased) – a man with whom she had a brief relationship and who has designated her as the executor of his will, she tells her husband, Mucho Mass – a used car dealer turned radio disc jockey – to look after the oregano in their garden as it has contracted a strange mould.

The mould on Oedipa’s oregano prompts an important question: is Oedipa asking her husband to look after the mould in some way critical to Lot 49? Is the mould perhaps the start of an epidemic that devastates the West Coast oregano and leaves the Italian restaurants in California in dire straits; is the mould going to be sorted by Maxwell’s Demon and thus generate a molecular heat capable of powering fridge, freezer and air conditioning units; is the mould actually going to have been placed there by Pierce Inverarity himself in the hope that, with her curiosity piqued, Oedipa takes a sudden and passionate interest in herbal-fungus, which will, through a series of evening classes, lead her to meet a man called Jackson McPhane – who will explain everything she ever needed to know about oregano mould, Pierce Inverarity’s assets and the poetry of Sir John Wilmot? Or is, in fact, the mould perhaps totally incidental to the plot, the reader and even Oedipa herself?

As far as I can tell – and I am so very ready to be wrong about this – the mould is incidental to the plot of The Crying of Lot 49. But it is still integral to getting a grip on what Lot 49 is about, because it is only by asking why the mould (and things like the mould) are there in each sentence that you can begin to tease out what is going on.

Questions abound. Why do we need to know about the oregano, we ask? Why is Randolph Driblette’s performance of The Courier’s Tragedy relevant to Pierce Inverarity’s will? What is the significance of Maxwell’s Demon? How has Dr Hilarious survived this long as a psychoanalyst? In asking about the mould on the oregano we end up asking about everything. Why do we need to know about any of this, or rather: what, in amongst all this, is important?

Every question the reader asks of Lot 49 is also asked by our avatar, the – as she puts it – executrix of Pierce Inverarity’s will, Mrs Oedipa Mass. From the off it is made clear that our lead is a novice, someone who “didn’t know how to tell the law firm in LA that she didn’t know where to begin.” To list the number of occasions in which Oedipa Mass is confused, perplexed, baffled or otherwise thrown by the plot and the world around her would come close to repeating the novel verbatim in a citation which would not so much plagiarise the text as pirate it.

In the course of what is, by any writer’s standards, a short book, but which for Pynchon is the equivalent of a scribbled note left on the fridge, Oedipa encounters scenarios that include and exceed the following: vagaries within the history of the delivery of post; a play called The Courier’s Tragedy by a playwright called Richard Wharfinger, described by the director as “no Shakespeare”; a molecular science prototype called Maxwell’s Demon, which “could sit in a box among air molecules that were moving all at different random speeds, and sort out the fast moving molecules from the slow ones”; a psychoanalyst who loses faith in Freud and lays siege to his own surgery from within; the geography, topography and demographics of southern California; a child actor turned lawyer who wishes to play a game of Strip Botticelli; a band called The Paranoids; a self-help group called Inamoarti Anonymous, for people who suffer from love, which communicates by a back street mail service; and a stamp collection that was once Pierce Inverarity’s pride and joy, which Oedipa never cared for, but which contains one forged stamp that details the post horn; a symbol of mail delivery, which either is or is not the key to the whole thing.

Forget mould on the oregano, The Crying of Lot 49 is a swirling tornado of detail that moves across so many fields of knowledge that no reader – or certainly not one I’d ever care to meet – is capable of having that volume of cultural and scientific references available on anything like a quick mental draw.

Given that this level of disorientation and confusion is something of Pynchon’s signature; that, as Richard Poirier has pointed out, it is unlikely that any of Pynchon’s characters could read – let alone write – a Pynchon novel, perhaps the most immediate mystery surrounding The Crying of Lot 49 is why anyone would ever wish to read the book at all. Or, to put it more crudely: if the mould on the oregano is there simply to demonstrate how everything in the novel is a possible dead end what, then, is there for the reader to pursue?

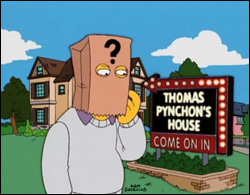

Thomas Pynchon is a notorious recluse. A writer who, when he won the National Book Award for Gravity’s Rainbow, let a comedian appear to accept the award on his behalf, and whose recluse status has itself been celebrated by no less a yardstick of American cultural values than The Simpsons. From no-one-knows-where (literally) he has managed to achieve not only critical acclaim but also a popular success normally reserved for mass-market thrillers; a unique achievement for any writer of literary fiction, let alone for one whose sentences seem to scream at the reader, why bother?

The reason for Pynchon’s success, and the reason why The Crying of Lot 49 is very much worth the bother, is perhaps hinted at by the sketchy author-bio above. Thomas Pynchon has a sense of humour. He clearly sees that there is something fundamentally hilarious about both fiction and the very idea of a fiction writer, and that it is only at this level of farce that a novel is able to be sure of anything.

Oedipa Mass is a hell-funny gal. She treats her paranoia with a deadpan charm that I will attempt to summarise here by quoting four classic Oedipa Mass gags:

- While attempting to resist a game of footsie with her lawyer, Roseman asks her to run away with him. “Where?” replies Oedipa.

- Stanley Koteks’s suggestion, with reference to Maxwell’s Demon, that sorting is not work, is met with: “Tell them down at the post office, you’ll find yourself in a mailbag headed for Fairbank, Alaska, without even a FRAGILE sticker going for you.”

- When a clerk pops up behind the reception desk of the American Deaf-Mute Assembly (Californian chapter) and starts signing at her, Oedipa considers giving him the V.

- Finally, at the novel’s end, with Oedipa starting to fear that the whole show has been set-up by Pierce as some sort of beyond the grave joke gone wrong, Oedipa declares to Genghis Cohen that “it may be a practical joke for you, but is stopped being one for me a few hours ago. I got drunk and went driving on these freeways. Next time I might be more deliberate.”

Oedipa’s gags give Lot 49 its charm. But they also cut to the heart of the novel; because, as much as Oedipa is chasing a hard ground on which to stand, and understand, to doso she herself must spin fiction.

On the opening page, when a drunken Oedipa discovers that she is Pierce’s executor, she first tries to think nothing and stare into the “greenish dead eye of the TV tube.” This does not work. What she ends up doing is imagining a whole series of scenes: a hotel room, a sunrise, a Bartok tune, and a bust of Jay Gould that Pierce kept on a narrow shelf above his bed. Quite whether all Oedipa’s imaginings are related to Pierce is unclear and unimportant. What is important is that Oedipa, on learning that Pierce has died, does not think nothing but instead starts sifting through the possibility of thought, right up until that bust of Jay Gould has, for her, toppled off that narrow shelf and landed on Pierce. “Was that how he died?” Oedipa asks. Really she has no idea, but when presented with a fact Oedipa delves straight into fiction, not to explain it outright, but simply to work out where to go so that it might be possible to understand.

The line between what is meant to be real to Oedipa and what it made up is constantly smudged at. In chapter two, Oedipa meets her fellow executor, Metzger, who is so good looking that Oedipa feels he must surely be an actor. It transpires that before becoming a lawyer Metzger was an actor and, by either a happy fluke or creepy scheming on his part, a film in which he starred is playing on TV. Oedipa and Metzger sit watching scenes whilst speculating on Metzger’s future in the film (which is clearly already fixed) while they own immediate future lies indiscernible and open. To add to the smudging of what is real to Oedipa, every time a commercial appears on screen it advertises a product or project, which, according to Metzger, Pierce either owned or had shares in. Rather than beginning the process of clearing up confusion, meeting her fellow executor has, for Oedipa, kick-started the process of becoming still more baffled.

What is and what is not meaningful becomes so faint in Lot 49 as to be indiscernible, with Pierce and Metzger and all the other people Oedipa meets looming large as both the potential for everything and the possibility of nothing. Oedipa, faced with this web of fiction, has to end up inventing her own, even when real events are still fresh in her memory – when she goes to the bathroom and can’t find her reflection in the mirror she is terrified into thinking she is not even there, before managing to recall that she herself broke that mirror a few moments earlier, while preparing for that game of strip Botticelli. But Oedipa’s fictions only ever seem to blur further: she leaps from drama, to science, to the history of the postal service; she forges links with characters who disappear when her quest moves on; and at the end of chapter three she is so intent on the significance of The Courier’s Tragedy that while listening to late night KCUF radio she fails to recognise that the disc jockey speaking is in fact her husband Mucho, whom she left with all those instructions for oregano care but days earlier.

Oedipa’s quest is disorientating for everyone, but above all for her. The more she attempts to uncover truth the more fiction she has to spin to get there, and the more fields of enquiry she has to delve into. Her search becomes so farcical that ground on which to stand and understand becomes more elusive not less. Randolph Driblette, director and actor in The Courier’s Tragedy, is less convinced by following fiction. He suggests to Oedipa that “the only residue in fact would be the things Wharfinger did not lie about”, but if Oedipa learns anything it is that fiction does not treat of truth and lies in a binary manner.

Communicating understanding is not as simple as Maxwell’s Demon because the act of sorting causes the system to lose entropy; it raises confusion; it uncovers more than it can cover up. When told that Pierce has died Oedipa can’t but imagine the bust of Jay Gould falling from that narrow shelf, even though she has no reason to ground that as fact.

By the novel’s end, Oedipa is constantly asking herself whether in fact any of what is going on means anything. Is it a clue to be solved? Is it all an elaborate game left by Pierce to haunt a former lover? Does it possibly mean nothing at all?

Pierce’s death forces Oedipa to project coincidence onto the chance events that occur in the chaos around her. To see a chance event as a coincidence is to fictionalise it; it is to pull the chance event from the oblivion of nothing and cast it verbally as the infinite possibility of everything. Or, as Maurice Blanchot puts it, the writer “ruins action, not because he deals with what is unreal but because he makes all of reality available to us.” What is a chance event in the world becomes coincidence when it seems to have been planned or arranged. But in Lot 49 that planning and arranging of chance and coincidence is delivered by Oedipa and the reader.

It is fiction both in the world and on the page that transforms chance into coincidence, because, as Pynchon is acutely aware, in fiction anything and everything are possible. This is precisely what is so funny about Lot 49; the idea that nothing does not in fact mean no-one thing, but in fact everything is farcical, and the novel attests to this on a line by line basis.

When Oedipa Mass first hears that Pierce’s will includes his stamp collection, she can only think of it as “another headache.” By the novel’s end she is left waiting for Lot 49 of the auction, hoping that a forged stamp with the strange postal symbol will provoke a secret bidder to make himself known; that another chance amidst chaos can, through Oedipa’s own fiction, become a coincidence endowed with meaning. In Lot 49 that which was at first trivial for Oedipa becomes essential through nothing more than the stories she has told herself about it. Lot 49 is the mythical end point. It is necessary that its crying lies beyond the end of the novel because Lot 49 is the possibility of Oedipa understanding, not understanding itself.

The Crying of Lot 49 does not then, mean any one thing, but nor does it mean nothing. It points to the possibility of meaning; that a dead end is in fact not something closed off, but rather something totally open.

About Thomas Chadwick

Thomas Chadwick is currently splitting his time between London and Gent, Belgium. His short fiction has been published in print and online and he was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize 2013.

The crying of lot 49 https://t.co/qo7KMj6EsR

Thomas Chadwick revisits a postmodern mystery – clues seem infinite and everything may mean everything … or nothing https://t.co/V3UKkfQlnX