You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

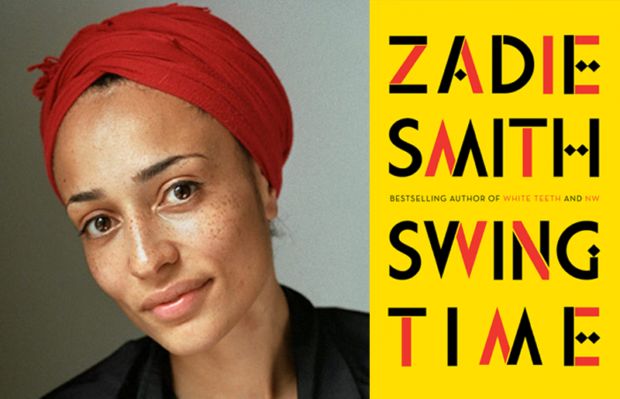

Zadie Smith’s Swing Time inhabits similar terrain to her other novels, her characters sharing the same upbringing in North London and concerns of race and economic disadvantage as those in White Teeth and NW. This is where the similarities end, however. Swing Time is unique in Smith’s oeuvre, being entirely narrated in the first person by an intelligent and amusing unnamed woman. The novel is a success: it is stylistically interesting, socially aware, funny and wise and – notwithstanding some dodgy writing by Smith – is deserving of a minor place in the English canon.

Swing Time is a classic bildungsroman – there is an emotional loss that makes the protagonist leave on her journey; there is a growing into maturity, which the narrator achieves gradually and with difficulty; and there is a conflict between the protagonist and the values of her upbringing, represented in her best friend, Tracey, which the narrator comes to accept, the narrator’s mistakes and disappointments then seeming to be over.

Divided into seven parts, like the seven ages of man, the novel tracks the mixed race narrator’s childhood and adolescence in an impoverished area of North London and early adulthood as a PA to an internationally famous pop star, Aimee. This takes her from the council estates of Willesden to New York and West Africa, these settings bringing an almost cinematic feel to the novel. Throughout this time, the narrator’s turbulent relationship with Tracey looms large. Their friendship is formed by their sharing of a similar skin tone: their ‘shade of brown was exactly the same – as if one piece of tan material had been cut to make us both’, and endures because of the shared experiences of their youth. Tracey acts as an anchor to the narrator, preventing her from escaping her roots and true identity as she gallivants around the world with the spoilt and superficial Aimee. Aimee (who at ‘only five foot two’ and ‘the palest Australian I ever saw’ is clearly physically based on Kylie Minogue) believes that ‘poverty was one of the world’s sloppy errors, one among many, which might be easily corrected if only people would bring to the problem the focus she brought to everything’ – a belief that leads to Aimee to set up a school in West Africa.

What makes Swing Time stylistically interesting is the movement back and forward between the present, and the near and distant past. Information is alluded to and withheld, then being revealed several chapters later. This technique is the impetus for the work. However, Swing Time is just too long for this to be truly effective, narrative nuggets being lost in huge swathes of the novel that could and should have been cut – sections that add little value (for example, the section on the narrator’s university experience felt like filler) and some writing by Smith that is difficult to follow. Particularly distracting is her overuse of long sentences, crammed with detail, parentheses and lists. A sentence describing the narrator and Aimee in West Africa that lasts for 92 words:

This element of roadside rolling chaos that so affected and disturbed me, like a zoetrope unfurled and filled with every form of human drama – women feeding children, carrying them, talking to them, kissing them, hitting them, men talking, fighting, eating, working, praying, animals living and dying, wandering down the street bleeding from their necks, boys running, walking, dancing, pissing, shitting, girls whispering, laughing, frowning, sitting, sleeping – all of this delighted Aimee, she leant so far out of that window I thought she might fall right through her beloved matrix and into it.

Swing Time, like Smith’s other novels, is socially conscious and full of intelligent insight into how various inequalities hinder people’s progress – in fact, little injustice escapes the sharp observation of the narrator. A description (in another example of Smith’s convoluted sentences and containing an egregious over use of the comma) of the patriarchy in the theatre world: ‘Socially, practically, sexually, a female star was worth all twenty chorus girls, for example, and Hot Box Girl Number One was worth about three chorus girls and all the understudies, while a man speaking part of any kind was equal to all the women on stage put together – except perhaps the female lead – and a male star could print his own currency, when he entered a room it re-formed around him, when he chose a chorus girl she submitted to him at once, when he suggested a change the director sat up in his seat and listened.’

This social consciousness is brilliantly mixed with dry wit and some-laugh-out-loud moments (take this as a warning if you are reading Swing Time on the tube), lightening what could otherwise be a heavy read. There is ‘the summer of the pissing doll. You fed her water and she pissed everywhere. Tracey had several versions of this stunning technology, and was able to draw all kinds of drama from it. Sometimes she would beat the doll for pissing. Sometimes she would sit her, ashamed and naked, in the corner, her plastic legs twisted at right angles to her little, dimpled bum. We two played the poor, incontinent child’s parents.’ In light of this it is curious that the critic at the Irish Times, who has myopically criticized Swing Time for lacking ‘an interesting voice or a compelling point of view,’ has slated the narrator ‘for lacking any discernible wit [and] intelligence’ – this critic found plenty of it, much to her embarrassment on her commute to work.

Swing Time is wise, not surprising considering that Smith is now 41 and on her fifth novel. A central theme is about the search for home (an appropriate one considering the genre of bildungsroman), the conclusion being that our true home is often the place we seek to escape: the narrator, after the glamour of working for Aimee, returns to Tracey, who lives in a North London council flat with her three children from three different fathers; Aimee would spend ‘whole a day in bed watching old episodes of long forgotten Aussie soaps … in moments of extreme vulnerability’; and the narrator’s mother – who spent her life trying to transcend her immigrant background through a ferocious obsession with education and activism – explains as she lies dying of cancer: ‘I dream a lot. I dream of Jamaica, I dream of my grandmother. I go back in time…’. Let’s hope that Smith keeps on dreaming, and keeps on writing.

Swing Time is published by Hamish Hamilton and is available in paperback from £5.75.

About Emily Bueno

Emily Bueno has an M.Phil in literature from Trinity College, Dublin. She has written for the Telegraph Culture section and the TLS. She is a trainee solicitor and lives in London.

A description (in another example of Smith’s convoluted sentences and containing an egregious over use of the comma) of the patriarchy in the theatre world: ‘Socially, practically, sexually, a female star was worth all twenty chorus girls, for example, and Hot Box Girl Number One was worth about three chorus girls and all the understudies, while a man speaking part of any kind was equal to all the women on stage put together – except perhaps the female lead – and a male star could print his own currency

https://eurotousd.info/

https://euro-to-usd.com/

https://printcalendartemplates.com/march-2018-printable-calendar/

thanks for the post..