You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingKaty Darby is the author of The Unpierced Heart (originally titled The Whores’ Asylum), a historical novel featuring a home for ‘fallen women’ in 1880s Oxford. Here, she reviews a reissue of one of London’s more unusual tourist guides on eighteenth-century prostitutes, and rounds up her top five loose women in literature.

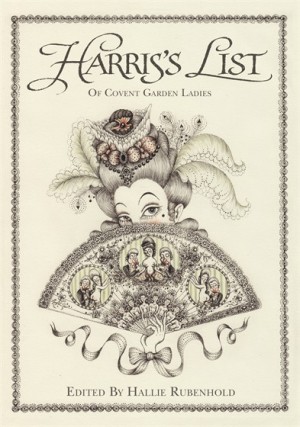

Harris’s List was an annual directory and review of prostitutes, indispensable to the gentleman-about-town of the eighteenth century. It’s ostensibly by Covent Garden maitre’d ‘Pimp General Jack’ Harris, but in fact, although Harris allowed his name to be used, the real power behind the quill was an Irish linen-draper turned rake called Samuel Derrick. Hallie Rubenhold, the editor of this new edition, is a historian, scholar and novelist with a particular interest in the beau-monde of Georgian London, and she is clearly in love (or perhaps lust) with her subject. She has previously written a biography of Harris, and introduces this little volume with a brief but fascinating account of Derrick’s life.

Harris’s List was a phenomenal bestseller in its time (250,000 copies, all told, over 38 years) which made its creators rich—and it’s not hard to see why. The range in this list is extraordinary, though not geographically—London was far smaller then, and a large number of the ladies seem to have lived on Cavendish Square, just north of Oxford Circus. But the List, besides naming and shaming the “Poxed”, includes “Foreign Beauties” (one from the West Indies, one from Boston), “Red-Heads”, “Perversions” and the “Buxom”. There are “good-natured” girls and beautiful girls—lesbians and “birchers”, dominant women, six-footers, Welsh and Irish and Northern women, who have all come to London to make their fortune as “votaries of Venus”.

In this reprint of particularly salacious selections from the List of 1793 (plus a few bonus reviews from other editions—of women notable for their size, lustiness, perversions or appearance), every page is a saucy treasure. Derrick spends most of his time euphemistically eulogising the ladies of the town for their neatly-kept or capacious unmentionables (although he never omits to note “fine teeth”, “a nicely turned leg”, glossy hair, “love-sparkling eyes” and so forth), but always includes prices and caveats: this one is short, that one has a bad temper, another is avaricious, and several have a “keeper” who might show up inconveniently. The List is obviously a practical guide, but done with such charm, humour and skill that it’s delightful to flick through looking for the best or most outré descriptions of these long-dead doxies.

Though most of the women reviewed are in their teens or early twenties, the more mature prostitutes are not neglected, with “Ladies of Experience” aged up to 56, though the author notes, “We should not have introduced her here, but that on account of her long experience and extensive practice, we know that she must be particularly useful to elderly gentlemen, who are very nice (picky) in having their linen got up” (i.e. as to who can get them aroused). In addition to these sorts of observations, almost every description, whether of a paragraph or several pages, is introduced by a line or two of verse apt to the subject—a lovely touch, even when the girl in question is far from poetical.

The best way to convey a flavour of this beautifully produced, liberally illustrated and highly entertaining little stocking-filler is to quote some of the best bits. Resist these charmers if you can:

Miss Ric__son, 14 Titchfield Street: (Her heaving breast with rapture lies/And love her every wish supplies) “She is fond of the sport to excess, and, by her own account, has never yet been blessed with a satisfying meal of manhood.”

Miss Harris_n, New Moulton Street: (Let the present hour be mine) “A pompous heroic girl, without either wit or humour, but fancies herself clever without any person acquiescing with her whomsoever.”

Mrs. Will__ms, 17 Pit Street: (Fond she is and e’er will be/Of our good king’s new guineas) “This is a fine tall lady, about twenty-four, a very fine figure, just returned from Brighton, has been in dock to have her bottom cleaned and fresh coppered (cured of venereal disease) where she has washed away all the impurities of prostitution, and risen almost immaculate, like Venus, from the waves.”

But pity poor Mrs. H_rvey, of 6 Upper Newman Street, who at only 26 “has been so good a friend to the good old cause, that the number of travellers who have gone the path to the fountain of love have trodden the grass away.” Either that, or she has a shaven haven—which doesn’t seem to do her any harm: “This attracts a number of Votaries, whose curiosity leads them to examine those curious parts.”

Save your guineas, though (this seems to be the average price, though the charges range from five shillings to a whopping £10—forty times as much), for Miss J_nson, who hangs around the Dog and Duck in Willow Walk, and whose “dairy hills of delight are beautifully prominent, firm and elastic, the sable coloured grot below with its coral lipped janitor is just adapted to the sons of Venus.”

Spicy, sensual and sometimes rather sweet, Harris’s List is an intriguing glimpse into a long-lost world of Regency bucks and “wanton and enchanting nymphs”. These days a tenner won’t buy you the dizzy delights of Chelsea’s Miss S_wyn, the priciest lady on the lust-list, but this charming little book is an excellent substitute.

And if the List has whetted your appetite for a certain kind of company, never fear. Though the ladies of Harris’s have long ceased to ply their trade, fiction is on hand to supply the lack. Some of the novel’s most intriguing characters belong to the world’s oldest profession, and the women on the list below are just a few fantastic examples of the many loose leading ladies of literature:

Moll Flanders in Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe (1721)

The ever-cheery Moll doesn’t have the best start in life—she’s born in the notorious Newgate Prison to a criminal mother, and after a brief interlude with foster parents, it becomes clear that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Having gone into service, she is seduced by her young master, and this leads to five marriages (most adulterous, some bigamous, one incestuous), ten children, twelve years as a thief, and finally Newgate—just like her Mum. But Moll is far too clever and lucky to stay there, and the reader likes her too much for Defoe to kill her off (as it usually happens with quite a few other fallen women), so at the ripe old age of 63 she gets her happy ending. Aw.

And if you like Moll you’ll also have a ball with John Cleland’s erotic classic Fanny Hill, published 27 years later in 1748 and banned in Britain until the 1960s for its scenes of flagellation and sodomy.

Juliette in Juliette by the Marquis de Sade (1797)

A companion piece to de Sade’s more famous novella Justine (which tells the story of a virtuous girl who is abused physically, emotionally and sexually by pretty much everyone she comes across), Juliette is the tale of Justine’s less upright sister—an amoral nymphomaniac who delights in sex and crime, and profits handsomely from both. The subtitle of the book is “Vice Amply Rewarded”, which should give you a clue that Juliette, like Moll, is another loose woman whose story, atypically, ends well. This sexual picaresque is about as plotless as most pornography, so you wouldn’t read it for the literary quality, but, this being de Sade, there’s some interesting, if rather nihilistic, philosophical conversations in between the relentless shagging.

Nancy in Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens (1838)

Bill Sikes’s mistress Nancy is a classic example of the woman who is irresistibly drawn to the bad boy who makes her life hell, but hey, “as long as he needs me…” She’s the original tart with a heart—living a life of thievery, prostitution and criminality, but retaining her humanity and compassion nonetheless. She’s motherly and protective towards Oliver, and in the end it’s her efforts to help him which lead to her murder by a furious Bill, who’s mistakenly convinced she’s shopped him to the authorities.

Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray (1848)

Thackeray’s classic satire is remarkable for many things, but most people remember it for its anti-heroine Becky. While she’s not strictly a courtesan, she is certainly a girl on the make who doesn’t mind flirting—and, it’s strongly hinted, sleeping—with rich and influential men in order to get ahead. Set at the time of the Napoleonic wars (1815 and after) Becky casts aside Georgian morality, such as it was, and pursues money and position as only a poor, low-born orphan can. Blessed with good looks, talent, charm, wit and brains, it’s amazing how far she gets—and how long she takes to come unstuck.

Sugar in The Crimson Petal & The White by Michel Faber (2002)

Sugar—no surname—is one of the most interesting and three-dimensional characters on this list, and possibly in all of modern historical fiction. Despite being flat-chested and ginger with a rare skin condition (icthyosis) she also manages to work as one of Victorian London’s most sought-after prostitutes, her specialism being… well, anything. She works her way up from Mrs. Castaway’s house of ill-repute by becoming the mistress of perfumier William Rackham—and eventually governess to his daughter. And then it all goes horribly wrong…

If all these women whet your appetite, you should also check out child transvestite Cherry Vanilla in J. T. Leroy’s Sarah, Tra La La in Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. Also read about Elisabeth Rousset in Maupassant’s wonderful short story ‘Boule de Suif‘ (which is also her professional name, meaning ‘ball of fat’) and, for a more modern twist, discover the arch saucery of the original Belle de Jour blog/book by Brooke Magnanti. Enjoy!

Who are your favourite loose women in literature? Share in the comments below.

About Katy Darby

A short-story writer and novelist, Katy was Editor of Litro Magazine from 2010 to June 2012, and is currently Online Short Fiction Editor. Katy studied English at Oxford University and Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich, where she received the David Higham Award. Her work has won several prizes, been read on BBC Radio, and appeared in various magazines and anthologies including Stand, Mslexia, London Magazine and the Fish & Arvon anthologies. Her first novel, originally titled The Whores' Asylum (Feb 2012), is The Unpierced Heart (Sep 2012), published by Penguin. Besides writing, she teaches Short Story Writing, Novel Writing, and a writers' workshop at City University. She also co-founded and currently runs the monthly live fiction reading event Liars' League.