You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingThere’s something odd in how we think about authors. We believe that what they create is so incredibly personal, and yet there’s not necessarily anything about their finished product – blog, novel, poem or newspaper article – that really shows who they are at all.

Unless a writer is particularly desperate (and, speaking from personal experience, some definitely are), you won’t find them standing next to a pile of their books in the store, pitching for sales, and unless you’re very lucky your copy of a book won’t come with a single pen-stroke actually written by the author. Reading is often imagined in terms of being allowed a look inside the author’s head, but at the same time you may not have any idea what that head happens to look like.

This may be part of the reason why there’s a long and noble in the writing world of people publishing under assumed names. George Eliot, George Orwell, Joseph Conrad, Lemony Snicket – they’re all carefully chosen personas, turning the flawed, real person (George Eliot was troublesomely a woman, Joseph Conrad bothersomely Polish and Lemony Snicket is a banker, not a very child-friendly or Unfortunate profession) into the kind of author they want to be seen to be.

It’s usually done with good intentions, and often we as readers know perfectly well that we’re being sold a kind of fantasy, but what about those writers who really do try to hide themselves behind another personality? When they get found out (as when Syrian feminist blogger Gay Girl in Damascus turned out to be not a girl at all, or even gay, but a Scottish man called Tom MacMaster) there’s a real feeling of betrayal among their readers. Authorship in the twenty-first century has become incredibly personal, and so a lie about that author’s personality turns everything they have written into an extension of that lie. Now more than ever, we think we know our favourite authors inside and out, and we expect them to be true to our images of them.

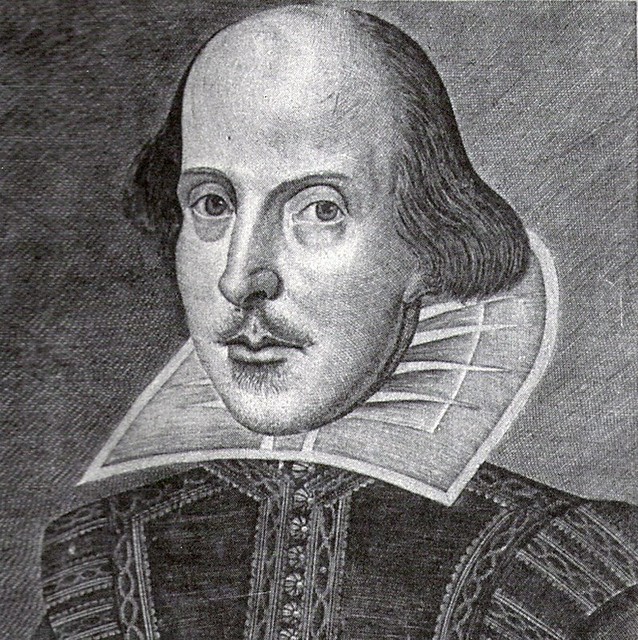

This deeply personal attitude to authorship is perfectly fine, as far as it goes, but it’s very important to remember that it wasn’t always this way. The mental image most people get when you say author to them – one person, alone in a room, pouring out deathless prose – didn’t really exist as a concept until the Romantic poets popped up at the beginning of the eighteenth century. They began having intensely personal Inner Feelings and, more importantly, getting them published. They made it fashionable for the author to be an individual, encountering the world on his own and responding to it in his own unique way. Before that moment, a writer’s identity simply didn’t matter as much – which, for us, is very difficult to imagine. We want our historical authors to be Personalities and because of that there are scholars who spend their entire lives trying to prove bizarre authorship theories – that Homer was a woman (or a slave, or a priest); that the Old Testament was written by five men with too much time on their hands – and, most famously of all, that Shakespeare was not the real author of his plays.

There’s a film coming out in the next few weeks – Anonymous, starring Rhys Ifans and directed by Roland Emmerich (he of Independence Day fame) – that aims to prove just that. Shakespeare, its line of reasoning goes, was nothing more than a patsy. The real creator of Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet and The Tempest was the aristocratic Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who was oppressed by cruel fate and had to hide his genius behind a pen name. Like most conspiracy theories, it leaves you mostly wondering why anyone would go to all that trouble without leaving any notes behind saying ‘It was me!’, but it’s also founded on a very modern, and so incredibly historically inaccurate, concept of authorship.

Images of Shakespeare hiding in a garret, beating himself over the head with Yorick’s skull, may be fun, but on investigation they just won’t wash. Writing in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries was less like Shakespeare in Love and more like a night at the pub. If you want a modern image for comparison, you can’t do much better than to imagine a group of guys all crowding round one computer, trying to decide how best to troll a forum. Everyone snickers and makes rude jokes and writes over each other, and even though the finished post has one person’s name on it, it’s really a collaboration between a lot of different, er, ‘artists’. Similarly, even though an Elizabethan play would be ‘by’ one person, it would have been through several different re-drafts on its way to completion, each of them handled by a different writer.

Author’s egos, too, were less of a concern. In the late fifteenth century, when Shakespeare was beginning his career as a writer, it was less fashionable to express your own feelings than it was to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Little boys had to write essays pretending to be William the Conqueror, or an Egyptian slave – who you were, and how you felt, didn’t matter as much. People who try to argue that Shakespeare had daddy issues, or was having a secret love affair, therefore, aren’t going to get very far – it’s like taking ‘The Flea’ as evidence that John Donne was actually a blood-sucking invertebrate.

Of course Shakespeare was a real person, with a life as complex and individual as our own, but he didn’t necessarily see himself – as either a person or an author – the way we would today. For the record, I firmly believe that he wrote all of his own works – but not in the way that you or I would now, if we were to go about the same project. In conclusion: love Shakespeare’s plays by all means, but don’t imagine him as a fifteenth-century hipster poet. He was just one guy out of a group, sitting round a table and making astonishingly creative sex jokes. And also some pretty great plays.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.

Thanks for the good sense about what I hear is a terrible film. Students were encouraged to collaborate and falsify opinions? Brilliant! Some call this cheating and plagiarism, but I’ll try it in my next Shakespeare class.

This is a brilliant piece of writing, indeed.

And the admin’s real swell as well… they instantly corrected the typo I brought to their attention.

Let’s just pretend there was no mistake in the first place, shall we?

Oh, wait, you already did, didn’t you? ;)

Mistake? What mistake! (Thanks mods!)

And Samuel – I’m not even sure that plagiarism as a concept really existed back then. But, er, don’t quote me as your excuse.