You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

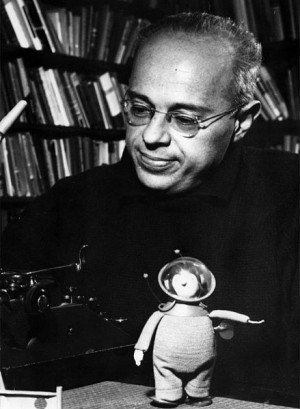

Go shoppingPolish writer Stanisław Lem is one of the most widely read sci fi authors in the world, his books having sold over 27m copies. His writing is strikingly different to his western counterparts, full of black humour, allegory and political satire. But poor translation of his work has meant he has often been misunderstood or underrated in the west. Polish journalist and Lemologist Wojciech Orlinski takes us through Lem’s enormous literary legacy.

A Young Man From Lviv

Your 18th birthday. For most of us, it involves some sort of rite of passage. From this day on, we are grown ups and society expects us to act like it. Do you remember your 18th? Some say that if you do, you didn’t party hard enough. I believe Stanisław Lem never forgot the day he realized his own childhood was gone. It was September 12th, 1939. On this day the Nazi troops approached Lviv in Poland, where Stanisław Lem has spent the previous 18 happy years as a loved son of an affluent doctor. This world was now gone forever. Because of who he was and who his parents were, the two biggest genocidal maniacs of the 20th century had put him on their respective death lists. If they ultimately failed, it’s only because they ran out of time. The Nazis soon withdrew from this part of occupied Poland, in accord with the secret treaty between Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop. Stalin took over Lviv, only to lose it two years later, when his former best chum Hitler attacked him without warning. And then he regained it two years later. Every time Lviv changed hands, people were slaughtered. To welcome their new overlords, some zealous specimens of the local population initiated their own pogroms of the Jews or the bourgeois. By all accounts they should have murdered the Lem family as well. Judging from scattered reminiscences from Stanisław Lem himself, it was a close call more than once. Staying alive by maintaining proper social connections and proper papers became a fine art, and the Lems excelled at it. Lem spent the best years of his life, between the ages of 18 and 25, witnessing the most horrible acts of genocide Europe has ever seen. Simply taking the wrong turn in the street could cost you your life, if you were unlucky enough to get caught in a random round-up and killed on spot just for being at the wrong place at the wrong time. These memories haunted him for the rest of his life. In His Master’s Voice, one of his best hard science-fiction novels, he puts his own memories into the mouth of a secondary character – a scientist named Rappaport, who, unlike Lem, emigrated to the USA in 1945, “the Holocaust having claimed his entire family”.

“He was pulled of the street, a random pedestrian. They were shooting people in groups, in the yard of a prison recently shelled and with one wing still burning. Rappaport gave me the details of the operation very calmly. The execution itself could not be seen by those herded against the building, which heated their backs like a giant oven, the shooting was done behind a broken wall. Some of those waiting, like him, in his turn, fell into a kind of stupor; others tried to save themselves – in mad ways […] suddenly the most precious thing to him was to preserve to the end the integrity of his mind, which would enable him to maintain an intellectual distance from the scene around him.”

Like his character, Lem survived a similar ordeal purely by chance. For some reason the Germans left the scene of murder. Maybe they had achieved their execution quota and decided to call it a day? We will never know. “He did not attempt to analyze what the Germans did, they were like fate, which one did not have to explain”.

It seems likely that the promise young Rappaport makes to himself – to preserve sanity against all odds – is based on a real promise Lem made himself during those days. Perhaps this is the origin of his trademark dark sense of humour. Life and death, freedom and oppression, it all boils down to some bitter joke in his stories about Trurl and Klapaucius and the various robotic tyrants they encounter during their famous sallies across the Universe. One of Lem’s earliest works, a one-man operetta discovered and published only after his death, was a joke about Stalin and Stalinism. During his student years he would perform it for a circle of his most loyal friends. Why risk your life for a joke? I think the young Stanisław Lem felt that since walking the streets could well kill him, it would be better at least to be killed for a reason. And a good joke seemed a pretty good reason to die for. In Polish literature you will find a similar sense of humour, based on absurdity and “intellectual distance to what’s around”, in the poetry of Wislawa Szymborska or the drama of Slawomir Mrozek. In fact, one could argue, that in terms of Weltanschauung (world view) and aesthetics, Lem’s works are not dissimilar to theirs. Lem pursued a different literary genre, but with similar sensibility. It is also perhaps not a coincidence that Lem, Szymborska and Mrozek were related to the same city, Krakow (where the Lem family relocated after 1945, when Lvov became Ukrainian). This ancient capital of Poland is no longer the seat of Polish government,but it still is the informal capital of Polish drama, poetry and literature.

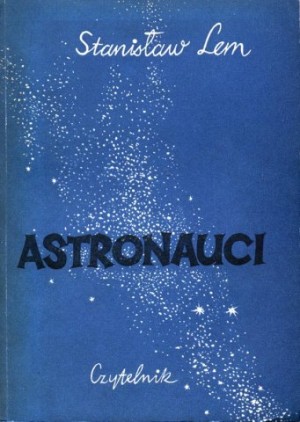

Krakow: Lem’s Golden Age

In this extremely creative milieu, Stanisław Lem entered the golden phase of his writing. In 1951 Stalin was still alive and it seemed he would rule the Kremlin forever. Initially Lem had planned to be a doctor, just like his father, but realizing that his entire class at the medical academy would be forcibly drafted — and in a Communist state, the army was not a nice place to be even during peace time — he tried to dodge the draft by delaying graduation. As early as in 1946, Lem had started to make some extra money by publishing a short pieces of fiction and, but now he made the decision to become a proper writer in order to justify his failure to become a doctor to the authorities. A chance encounter at the mountain resort of Zakopane with the editor of the publishing house Czytelnik gave Lem his opportunity. The editor wanted to publish the first Polish science fiction novel, and Lem decided to write it. So Lem became a writer just as he had survived the Nazis; by chance. The contract was signed and the novel, The Astronauts (Astronauci), released. It describes the first manned mission to Venus in the early 21st century. It is rather juvenile, but compared to Western sci fi of this era, it holds its ground. The golden phase of Lem’s creativity began around 1956, when communism in Poland evolved from the genocidal Stalinist phase into a period called “The Thaw” (from a novel by Ilya Ehrenburg). It was still a dictatorship, but now without random executions. Lem’s creativity in this period is nothing short of breath-taking, as he turned out one masterpiece after another. Many of his novels from this period are so good they would have made Lem famous if that had been his only achievement. Yet Lem was able to publish another equally good book even during that same year. It all started with the creation of Ijon Tichy, Lem’s intrepid star explorer, whose adventures are chronicled in the Star Diaries cycle. This grotesque character could be the joint brain-child of Douglas Adams, Jonathan Swift and George Orwell, and I like to imagine all of them shaking Lem’s hand in an afterlife for atheists. First stories featuring Tichy were published in 1955, the last one in 1999. Then came Eden (1959), a novel which set the direction of science fiction for all the other writers in the Soviet Bloc. It’s a story about human astronauts crash-landing on an inhabited planet and undergoing a horrible, genocidal social experiment meant to create a perfect society, but resulting mostly in mass graves. The allusion is pretty clear to anyone reading it, even more so back in 1959. But any censor who said “I see what you did here” would have put himself in a precarious situation, in admitting that Communism might have something to do with death camps and mass graves. So it was much safer to pretend not to see the refernece. After Eden, many other writers followed this path.

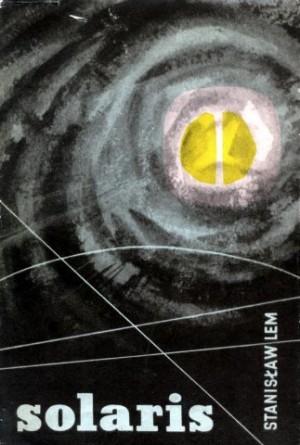

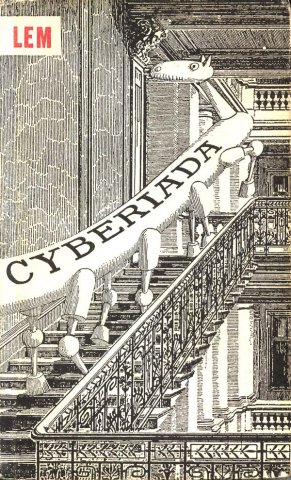

But Lem already had other ideas in mind. In 1961 he published Mortal Engines, a collection of short stories about robotic societies undergoing a Medieval collapse of civilization. The implication is that this is some time after their successful rebellion against a previous civilization of “palefaces”, that is, us. This idea was to evolve into Lem’s masterpiece The Cyberiad, featuring robots Trurl and Klapaucius, living in the same Medieval universe. The same year, Lem also published Return from the Stars, a brilliant book about astronauts returning to earth after 127 years in space and finding societal changes so advanced they are unable to adapt. The same year came Solaris, his most famous book, about the failure of human contact with a sentient planet, filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and later by Steven Soderbergh in 2002. The same year again, (yes, that’s right, we are still in 1961!), Lem published Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, a Kafkaesque dystopia of paranoid militaristic bureaucracy set in some near future. But Lem was not satisfied with writing only fiction. In 1964 he published a formidable essay Summa Technologiae, featuring predictions of the main technological challenges for the near future. Lem discussed genetic engineering, virtual reality and nanotechnology, although without using those words, as none had been invented back then.

And he kept on writing. First The Invincible, a hard sci fic novelette about astronauts fighting a swarm of nanorobots, followed by The Cyberiad. In 1968 came His Master’s Voice, about a group of scientists trying to decode a message discovered in a flow of neutrinos, a scientific premise that is still valid today. And in 1971 Lem wroteThe Futurological Congress, a blackly humourous novel featuring Ijon Tichy, which is currently being adapted for film by the acclaimed Israeli director Ari Folman. Lem then began his Apocrypha, fictitious reviews of books that nobody will ever write. Readers back then had problems getting this particularly weird joke, but now Lem’s Apocrypha are among his most popular stories. One of my personal favourites is a fictitious review of a book called Sexplosion, chronicling a post apocalyptic history of a mankind that has entirely lost its sex drive due to some unspecified catastrophic event in 1998. Mankind has survived – just about – thanks to some patriotically minded people able to “lie back and think of England”. In Poland, the youth have rebelled and defected to asexual guerilla groups in the forests,. and everyone enjoys colour images imported from Denmark (now we would say downloaded from the internet) depicting eating scrambled eggs by a straw, and other perverse consuption – the vacuum had to be filled, one way or another.

Leaving Poland, and Science Fiction

In 1981 martial law was introduced in Poland. Stanisław Lem left the country, and, for his German publisher, wrote his last and saddest novel, The Fiasco. This work can be understood on many levels. Literally speaking, it’s a story of a failed attempt to establish communication with an alien civilisation. But it is also Lem’s farewell to science-fiction – a literary genre that has failed to provide us with a vision of the future. And on yet another level, it could be also seen as representative of Lem’s personal feeling of failure over his semi-exile. Lem never wrote another novel. But he remained an active essayist and columnist, to his final breath. After his return to Poland in 1989, he was active in the Polish media, chronicling the development of the young Polish democracy and the birth of cyber-culture – a phenomenon he had once theorised about. In both cases, his view was pessimistic, to say the least. He warned us, the Polish citizens, that we abuse the liberties our ancestors fought so hard for. He was also bitterly disappointed by the internet – to his disgust, the network created to facilitate scholarly research turned out to be used mainly as a tool to facilitate moronic conversations and pornography. His very last column, published just before his death in 2006 in the Krakow-based weekly Tygodnik Powszechny, was in a lighter mood. A Russian website, Inosmi, had collected questions from Lem’s Russians fans to put to him. “I wanted to deal with the misery prepared for us by the Kaczyński brothers [Polish politicians Lech and Jarosław Kaczyński] – I dislike very much the extreme right on rise in Poland recently – but suddenly like a truncheon on the head, I was hit by 52 questions from my Russian fans (…) the barrage of praise overwhelmed me” – he wrote. This is so Lem! Even on his deathbed, hit by a “truncheon of praise” from his fans, whose compliments did not allow him to do what he loved the most: complain about the absurdity of politics and civilization. Thankfully, his complaints will be with us forever in his books, now available on the digital readers Lem predicted as early as in 1953 in his novel Magellanic Nebula.

About Wojciech Orliński

Wojciech Orliński is a Polish journalist, writer, and blogger. He is a recognised authority on "Lemology", and published a book on Stanisław Lem in 2007. Since 1997 he has been a regular columnist for the Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper. He has also published science-fiction stories and opinion pieces in Nowa Fantastyka.