You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingThere are some words that are worth keeping, I’ve always thought. Everyone has their favourites – my friend Neil always swears by cornucopia. Defenestration seems to come up quite regularly. I’ve heard a case made for infinitesimal, although I’ve always had a soft-spot for chevron. But there are thousands of beautiful words I encounter, think ‘oh what a lovely word,’ and then promptly forget. So, I’ve started word hunting, keeping good words I find, just for their own sake.

Old books are ideal for word hunting. Sometimes, opening one is like lifting a stone and surprising the words like woodlice. Non-fiction is ideal, and the more obscure the book, the better the words. In fact, the book itself doesn’t much matter – it’s just a receptacle for its words. I usually don’t even keep the books I collect words from; I reap and get rid. It’s the words that count in this game.

Old books are ideal for word hunting. Sometimes, opening one is like lifting a stone and surprising the words like woodlice. Non-fiction is ideal, and the more obscure the book, the better the words. In fact, the book itself doesn’t much matter – it’s just a receptacle for its words. I usually don’t even keep the books I collect words from; I reap and get rid. It’s the words that count in this game.

In a secondhand bookshop I found a handwritten shop ledger for a drapers from 1876, belonging to a Master Williams, who wrote his name in a flowery, slanting hand inside the cover. It lists invoices for the orders of cloth going out of the shop. That’s all that’s in the ledger, an everyday thing probably forgotten about once it was full. But it’s a hoard of beautiful words. Here’s a taste of the ones I kept:

In January Master Williams sold shalloon, silk serge and Saxony doeskin, Scotch sheeting, swansdown and India silk handkerchiefs. In February, rough loom, red chintz and Russia duck. In March it was lutestring, lace cardinal and linen huckaback. In April there was calico, cambric and cashmere shawls. In May crimson velvet, Paramatta Cloth, damask and drab moleskin, and in June black crape, bombazine and black moiré. Even to list the words is to start writing a poem.

Word hunting can uncover tiny stories too –in the draper’s ledger, customers spring to life as potential characters for stories. I like to picture the Reverend Steward, who wanted fine white counterpanes and Wilton blankets, standing tutting in the queue behind the more stylishly inclined Reverend E Boyce, ordering a silk umbrella and two pairs of kid gloves. And I think it’s hard not to make assumptions about a Mr. Robert Barnard, who ordered buck-skin braces and mohair socks.

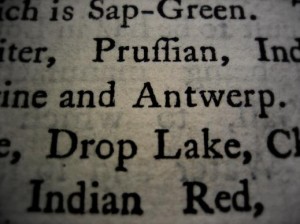

Another word goldmine I found once was something called The Art of Painting in Miniature. All that was left of it were some loose pages held together with a couple of ragged threads. It looked like it might be 18th century (the letter “s” is written as “f”), and the author, whose name is missing, is informing the reader about the types of paint used for miniatures. The words (with their old spellings) are luscious. Verditer, Prussian, Indigo Smalt, Carmine, Drop Lake, Chinese Vermillion, Indian Red, Gall-Stone, Terra Sienna, Roman Oker, Sap-Green, Lamp-Black and Flake White

And the tiny story is there too, in all its smelly, dirty, 18th–entury detail: “I would recommend my readers to apply to the slaughtermen at the Victualling Office, or any private slaughter-house who will examine the gall-bladders of the oxen, in many of which gall-stones (being concrescences formed in the bladder) are found; by this mode only, will the artist or amateur attain possession of this unrivalled colour in its pure state.”

Sometimes the most technical books are written like poetry. A Catachism of the Laws of Storms, written by a John Macnab in 1884, is a textbook for trainee sailors on how to navigate through bad weather. The instructions are dry and technical, but the words conjure up the terrifying storms themselves, which John Macnab clearly maintained a healthy awe of. He warns against ragged, immense, pyramidal seas, long rolling and wild with their great rotating, spherical squalls and storm-fields, oscillating and overwhelming as they veer and shift on the outer verge, the cross seas hiding calm centres.

I’m never quite sure when my word collections are going to come in handy, but they always do, sooner or later. Flicking through an old notebook and being delighted all over again by bombazine, verditer or images of squally storm-fields usually sparks off ideas for stories, poems or character names. It’s my belief that some of the most beautiful poems and stories were inspired by their authors’ experiences of word hunting. John Masefield’s poem “Cargoes” is my favourite example—”Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir…” I’d put money on the fact that he came across the word quinquireme at some point in his sea-faring life, (it’s a kind of ship) and the rest of the poem followed, even if it was years later.

If you’ve discovered your own unusual favourite words, I’d love to hear them. Use the #favouritewords hashtag on Twitter to let them loose on the world.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.

Thanks for sharing, please keep sharing with me USPS tracking