You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Amboy is a place in the Mojave desert, about 200 miles east of Los Angeles. I hesitate to call it a town: undoubtedly that’s what it used to be, and maybe once a town is always a town, but right now, and for the twenty years or so that I’ve been visiting, its population wouldn’t qualify it as a village, not even as a hamlet. There are SUVs driving down the freeway with larger populations than Amboy, and the freeway is precisely the reason for Amboy’s demise.

Amboy sits along a stretch of Route 66, the Mother Road, the place allegedly, formerly, to get your kicks, and when, in the 1950s, the Interstate 40 was built, some ten miles to the north, the serious cross-country traffic went there, leaving Amboy behind, to fade and desiccate, and remain a kind of rough time capsule. But if I hesitate to call Amboy a town, I hesitate even more to call it a ghost town. The place has certainly been abandoned and neglected. Parts of it have certainly decayed and crumbled, and parts of it do indeed lie in ruin, but not all of it, and not all of it conspicuously. The most important parts, the most eye-catching, don’t look like ruins at all, at least not at first glance.

What’s there looks, from a distance, remarkably well-preserved. There’s a school, a gas station, a church, a motel, a graveyard, a post office: the last of these is even fully functional, but a close look reveals considerable ruin elsewhere. That church, for instance, which is actually a bare meeting hall, has a wooden tower with a cross on top, and although the walls are bright white and appear recently painted, the tower is leaning precariously, a little more every time I visit, and I don’t doubt that one day I’ll arrive there and find that gravity has completed its work. Part of the motel consists a long row of neat, minimalist white cabins that look intact, and even habitable. But they’re not. A closer look reveals that these cabins, which you can walk right into, are empty, with no furniture, no plumbing, no power, with the tatters of old linoleum on the floor, many windows smashed, broken Route 66 Cola bottles strewn around the floor.

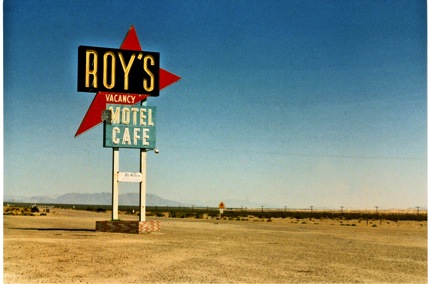

The gas station probably can’t be considered a ruin at the moment, since it currently has gas for sale, though there were many years when it didn’t. There was a period when dangerous-looking yet surprisingly friendly bikers would hang out there on Sunday afternoons, selling only slightly over-priced beer from an ice-filled cooler. They did a reasonable trade, I think. Plenty of people stop in Amboy, it’s hard not to. Right between the gas station and the motel is one of the greatest, stop-you-in-your-tracks, roadside advertising signs I, or anybody else, has ever seen.

The sign says Roy’s Motel Café, and it’s a classic all right, tall, formidable, red, black and blue, two rectangles and a downward-pointing arrowhead, a smack you in the eye typeface, and more to the point, right in the middle it says ‘vacancy.’ Many a photographer (not least William Egglestone, who photographed it back in the day when there was often a classic black and white police cruiser parked outside), has embraced that visual and verbal pun: gas, food and lodging here, nothing but vacancy down the road. Is that a bit too obvious, a bit too much of a cliché? You bet. And so the sign has appeared in a endless movies, music videos, TV commercials, and photoshoots.

This is the secret of Amboy’s success. Although it has defining elements of ruin, it has other elements that define it as a stage or movie set, as a moody, evocative backdrop, as a location. This inevitably creates certain problems for people (such as me) who yearn a certain (and admittedly contested) authenticity when they’re walking in the desert and/or walking in ruins.

In fact there’s at least one place nearby where people do some more or less conventional, and fairly strenuous, desert hiking. The Amboy Crater is just a few miles to the west, an extinct cinder cone volcano, two hundred and fifty feet high, surrounded by a black lava field. It’s a popular enough walking location that I’ve even seen tour buses unloading some extraordinarily well-dressed sightseers there, though I didn’t stick around to see how far they walked.

But let’s face it, an extinct volcano in the middle of the desert barely fits within even the broadest notion of ruin. If you’re looking for ruin, and I usually am when I’m in the desert, you have to look elsewhere, and as it happens Route 66 is not the only transport artery to run through Amboy. There’s a railway line too, a cluster of tracks that run parallel to the road, a couple of hundred yards to the south, and the railroad is still very much in business. If you hang out in Amboy for half an hour or so, chances are you’ll see a couple of immensely long freight trains roll through, the initials BNSF on the locomotives, standing for Burlington Northern Sante Fe.

Railways always strike me as the most appealing and picturesque of forms. Who doesn’t like to watch the trains go by? Who doesn’t like to stare down the tracks towards the vanishing point? And yet cities, buildings, landscapes, even small desert towns, so often turn their back on the railway. Trains thread through the bad parts of town, behind high walls and fences, in cuttings and tunnels, present but not seen and not regarded. Meanwhile the land beside the tracks becomes a no man’s land where debris collects, where things get dumped, where graffiti are largely tolerated because at least they’re not somewhere more conspicuous. In the desert however, the railways have nowhere to hide.

And whereas in England every yard of track is fenced off in an attempt to make it inaccessible and supposedly safe, here in the wide open spaces of the desert, nobody has the time, energy or money to fence off all those thousands of miles. A man can walk right up to the tracks, walk across them, along them if he wants to. Oh sure there’ll be the occasional no trespassing sign, but who’s going to take any notice? Who’s going to police it? And of course dumping goes on there with a casual lack of inhibition. Down by the tracks in Amboy there used to be a sign that said no dumping, standing guard over a great heap of garbage.

And let’s face, it the railway people themselves are a messy bunch. In Amboy there’s a sprawling three-sided corral where they’ve stored, or at least stashed, various bits of miscellaneous railroad hardware; posts, coils, wiring, chunks of lumber, those glass and porcelain electrical connectors, though those tend to be smashed if they’re not stolen. You can walk into the corral, pick around, and although there isn’t a sign saying ‘help yourself,’ equally there’s no sign saying ‘keep out,’ and you can’t help thinking that if you had a use for some scrap fence posts or wiring, the guys from the BNSF would understand, and definitely wouldn’t put much effort into stopping you.

As I turned my back on the preserved charm of Roy’s Motel Café and Route 66, I was aware that maybe I wasn’t so much walking in ruins as strolling around in mess, performing the pedestrian equivalent of making mud pies, as I admired stacks of old sleepers and heaps of ballast. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, but sometimes it’s good to aim a little higher, so when I noticed a fine, low slung industrial building maybe a third of a mile away along the tracks, I decided to walk over and explore. I accepted that this wasn’t ruin exploration on the grandest scale, but we all have to do what we can.

From the road, when I set off walking, I couldn’t have said what the building was intended for, something to do with the railway obviously, perhaps loading and unloading, possibly concerned with storage, though there was no indication that anything was going on there at the moment. At first I thought it was made of white painted metal, and the paint had rusted or flaked off, but as I got a little closer I realized the walls were broad slabs of wood, and the paint had peeled away in long vertical strips giving the effect of corrugations. Up against the side of the building I could see storage tanks, some palates, a mobile scaffolding tower, and there was a chain link fence around the whole thing, serious but hardly impenetrable. There didn’t seem to be much in there that anyone would want to steal. I guessed they were trying to keep out vandals and graffiti sprayers, but since I was neither of the above I eyed the fence and wondered if I should do a little creative trespass, shimmy over and go inside.

I walked a circuit of the perimeter. A railway siding ran alongside the back of the building within the fence, and there was no sign of life or activity anywhere. The big roller doors on the building were raised and you could see there was nothing at all inside. I got the impression that if this place was still being used for anything, it wasn’t much and it wasn’t recent. I decided I’d go in.

And then suddenly I realized the place wasn’t deserted after all. Around the side next to some half-demolished walls that looked like they might have belonged to a coal bunker, there was a single, pristine, dinky little golf cart with a canopy, a thing wildly out of place in this battered, industrial desert scene, and sitting in the cart was a huge man, dressed all in white. As I remember it he was wearing a solar topi, though I think I may have made that up in retrospect: it may just have been a floppy sunhat, but nevertheless the overall effect was undoubtedly grand, spooky and strangely ethereal. He looked both ghostly and angelic, unworldly, very, very still, not remotely right for this location. He was also wearing wraparound shades, and he was smoking a long thin cigar, and he reminded me, improbably, of Marlon Brando, certainly not as he was in The Wild One, and only partly as he was in Apocalypse Now, but rather as he appeared in The Island of Dr Moreau, where he dresses in white gauze, presumably to hide his bulk, with his face coated in white pancake for reasons known only to himself. I’m prepared to believe that time and my imagination may have glorified the stature and strangeness of my man in Amboy, but not by much. His presence seemed genuinely uncanny and alarming. A man who can invoke Marlon Brando, a ghost and an angel, while sitting in a golf cart obviously has an undeniable aura.

I think he must have seen me before I saw him, because I only spotted him as I was reaching for a handhold on the chain link. The sunglasses ensured there was nothing so unsubtle as eye-contact, but he turned his head just a fraction in my direction, then back again, the subtlest admonitory shake of the head, as if to say, ‘I wouldn’t do that if I were you. I wouldn’t do that if you know what’s good for you.’

I like to think I know what’s good for me. I stepped away from the fence, calmly, unhurriedly, walked on, went about my business, and eventually I headed back to the car, parked up by Ray’s sign. My wife was waiting for me there: she’d been off in the other direction looking at the graveyard (it’s good to have related but separate interests), and she asked me what I’d been doing.

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘I think I saw the god of the ruins of Amboy.’

‘Was he on a train?’

‘No.’

‘Was he walking?’

‘He was on a golf cart.’

‘Makes sense. What’s that in your hand?’

What I had in my hand was one of my great desert finds. Yes, yes I pick stuff up in the desert and take it home with me. Not so long ago it was thought of as perfectly OK to collect rocks or fossils or antlers or even plant specimens from the desert: now this is regarded as environmentally unsound, as messing with nature, as pure evil. So now I only pick up stuff that doesn’t belong there, that’s been left of dumped by humans: hub caps, unfathomable innards from bits of machinery, the occasional abandoned children’s toy. The best stuff is up on the wall of my garage. And what I’d picked up that day, after my encounter by the chain link fence was half of one of those diamond-shaped metal signs that they put on the back of vehicles, in this case railway cars, warning of dangerous cargoes. This one, in full, would have read ‘Spontaneous Combustion,’ but since I only had the left hand half, it reads Sponta Combu – a great name for something, a band, a spy, a guru, an Indian fusion dish – or maybe one of the 99 names of the god of the ruins of Amboy.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.