You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The thing is I’m actually the real deal, not one of those fakes or tricksters who prey on people, who take advantage of them and make a few dollars out of their problems by keeping them happy, telling them what they want to hear. For them it’s an act, a show; a game both sides play and everybody knows the rules. For the tourists it’s just one of those things they do when they come to Macau, along with eating, shopping and gambling. These days even the tourist office hands out guides. Me, no I’m the real thing, I truly can see into the future, and believe me I wish I couldn’t. It’s rarely anything to look forward to.

*

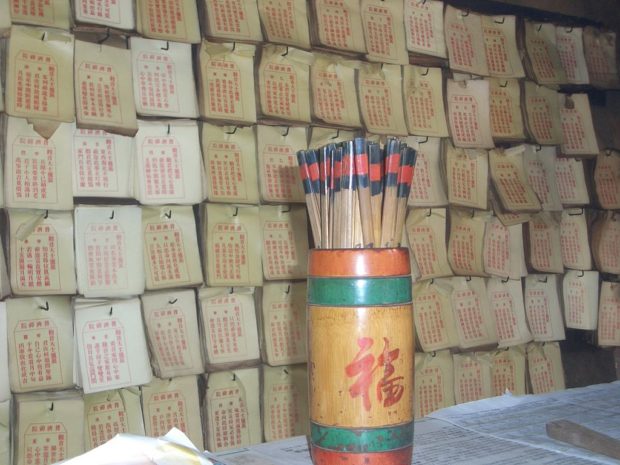

I have a client booked in for this morning. In the past I worked the temples and the night-markets like the street-performers. I did kau chim reading the sticks and interpreting the oracle, I was a master of face reading, palm reading – all the stuff I had to do to make a living, I went through the motions of what the punters expected of me, even though I could have answered their questions without any of that fakery. These days I’m an old man and I just do it my way; I don’t care much for going out so I prefer to stay indoors, but luckily my reputation is such that I don’t have to spend all day at the temple and instead they come to my apartment.

Today it’s a young woman – a Miss Chan, no more than twenty – whose mother has cancer. I can tell she’s doubtful, wondering what she’s doing in this somewhat tatty living room. She’s attractive and smartly dressed in a modern style; jeans, a Versace T-shirt – or at least a Versace knock-off – and a gold necklace. Her looks only serve to emphasise the drab emptiness of the room. For the past few months I’ve been slowly getting rid of things, divesting myself of a life, and there isn’t much furniture left, just the little I still need, but I ask her to take a seat on the worn black leather sofa that continues to take up one side of the room. A framed photograph of my parents hanging on the wall behind her is the only decoration.

I always like to let the client start so I pull over a chair and wait for her to speak. When she does her voice is quiet and hesitant, and I can only just hear her over the sound of the ceiling fan gently stirring the air above us.

“I’m not sure why I’m here…” she starts. “I’m sorry, I don’t mean to be rude but I don’t believe in all this mumbo-jumbo.” I don’t take offence; the young ones are always like that. They pretend not to believe and yet still they come. The older generation believe implicitly without any apologies.

“There is no mumbo-jumbo, Miss Chan. I have certain skills, that is all.”

And that’s the truth of it, I’ve always had this ability. Ever since I was a boy. I was seven when out of the blue I announced to my parents “Big Uncle’s going to die.” Big Uncle was my grandmother’s brother, I called him Big Uncle to differentiate him from my parents’ brothers. He lived alone on Coloane down a dirt track completely out of the way with no neighbours anywhere close and to my younger self he seemed ancient, though in reality he was about the same age I am now. We had just left his house – I think my parents had wanted his opinion on something – when the words came out from I know not where. I must have shocked them, I surprised myself. My father told me to be quiet and stop being so disrespectful of the elderly, but later my mother was friendly and took me to one side and tried to explain how one day we would all die. “No,” I said, “I mean he’s going to die tomorrow.” My mother drew back and slapped me hard across the face, sending me to bed with no supper.

The next day Big Uncle died. A massive stroke that came out of the blue while he was playing mah-jong in the tea-shop.

They are always looking for hope, that’s the worst of it, but because I know the truth hope is the last thing I can give them. Miss Chan wants to know that her mother will recover, that all will be well. But it won’t and there’s nothing I can do to change that. I can already see that her mother will die shortly, all I can do is to try and tell her gently.

It will be a relief in some ways when all this is over.

*

When it comes down to it people always ask about the same three things: health, business and love. I suppose these are the subjects that matter to us most. Will my mother get better? Should I invest in this stock? Will he make a good husband? I used to wonder why I only had bad news to give but in time I came to understand that people only go to a fortune-teller when they have doubts, and their doubts were usually well-founded. You don’t waste your money when you know you’re in love with someone. Just now and then I was surprised and able to give good news, but that wasn’t often. More often, like today, an illness was incurable, a business investment unwise, and a lover unfaithful.

The grief everyone felt over Big Uncle’s death overshadowed my prediction, which was somehow forgotten. Over the years I’ve tried and failed to understand how it works, but when I was very young my skills were limited, crude. I could only see the most dramatic close events. As I got older I was able to refine my abilities, to see things that were subtler and further away. To begin it seemed a blessing – friends and family sought my opinion on everything and I was always popular at the dog track – but in time it became relentless. It wasn’t enough that I could see answers to specific question; no, images of the future started to come on me unasked. I could be walking down the street and the destiny of strangers passing by crowded in on me. I was being overwhelmed by the future, deafened by the fates of everybody around me.

Relationships became impossible. How could I love someone when I knew exactly what they were going to do or what was going to happen to them? When I was twenty I went out with this girl for a while but soon I knew she was seeing someone else. She denied it and when I told her they were going to spend a weekend together in Hong Kong she said that was nonsense. Two days later she discovered that her new boyfriend had bought the ferry tickets. Girlfriends became suspicious of me, of my motives, of everything I said and did. They wondered what I knew and sometimes predictions became self-fulfilling.

The worst of it was when my parents died; my father went first, twenty years ago, and then my mother. Of course I knew, and they must have known that I knew, but it’s the only time I’ve ever lied about the future. With my father I had a general sense some months in advance which became stronger and more definite as the weeks progressed. When he fell ill my mother asked me “Will he recover? You must know, so tell me, please.” I fudged my answer, I didn’t want to lie but I couldn’t tell the truth either. I said that I couldn’t see clearly, I said that perhaps I was too close, that with family my vision was clouded. I doubt if my mother believed me and a year later when she started having heart trouble she asked me to be honest with her. She said she wanted to know so that she could put things in order if she had to.

Telling my mother she had only three months to live was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. That’s when I retreated to my apartment here in Coloane, staying indoors away from people as much as I could. I’ve become something of a monk or a hermit and I think I understand now why Big Uncle lived here: it’s as close as you can get in Macau to the middle of nowhere. I still need money to live on though, so I started taking private appointments.

*

Miss Chan tells me about her mother.

“The stomach pains started two years ago. I think. They may have started before that but my mother never said anything. I think she kept quiet about it, didn’t want to worry my father.”

“Tell me about them, your parents.” I don’t need to know, but she needs to tell me. Sometimes I’m part-therapist.

“They run an antiques shop. It doesn’t really make any money but it’s my mother’s love. My father … he’s not very practical … I don’t know how he’ll cope if anything happens to her…”

I have to decide whether to tell her that her father will die of a heart attack a few months after her mother, literally broken-hearted. I often have this dilemma, they come to ask me about the future but how much do they really want to know? Do they want the whole truth? I can’t be dishonest, I will never lie to them, but I can decide how much to tell them. This time I elect against telling her unless she asks specifically, it’s her mother she’s come about not her father.

“My mother…?”

“I’m sorry, Miss Chan…” I don’t need to say anything else. I think about taking her hand but she draws herself inwards and I leave her to her thoughts for a time.

*

Miss Chan spends an hour with me in the end. I don’t need all that time to tell her what she needs to know, but she needs the time to take it in. She’s my final client and I’m in no rush, and anyway there’s something about her that I respond to. We seem chalk and cheese, oil and water, but I’m drawn to her. Not in a sexual way – not at my age, and certainly not now – but I sense a connection. That’s unusual. For all that I can see everything about a person’s life, it is always very abstract; I feel no more about them than I do the weather. But with Miss Chan it’s different, I’m sorry for her of course, but more than that there’s something about her I can’t see clearly, and that intrigues me. Normally I can read people completely, but not with Miss Chan. There’s a curtain; yes, I can see what will happen to her parents, but nothing about herself. She blows her nose as she starts to gather her things, there have been a few tears, but I don’t want her to go. Another thing that is unusual, normally I’m anxious to be alone again.

“Would you like some tea before you go?” I ask. She looks at me, she seems troubled by something beyond her mother, and accepts the offer. I go to the kitchen and when I return with a teapot and two cups, she is the one who takes my hand.

“Are you okay?” she asks. “Can I help? Is there anything I can do for you?”

At first, I’m surprised by her questions, it’s as if our roles have been reversed. Only slowly do I begin to understand.

“You know?” I ask.

“I’m sorry,” she says.

“There’s no need to be. I’ve known for a long time now. I’m prepared for it, it will be a blessing in some ways, but I wasn’t prepared for this. For you knowing. You can see, can’t you?”

“Yes.”

She says this calmly, very matter of fact and without much emotion. Perhaps that’s a good sign for her future, she’ll need to keep a sense of detachment.

When Big Uncle died I was too young for it to register, but there were family stories about how he had second sight, and when I was a young man I came to understand that somehow his skills came to me when he died, an inheritance of sorts, a transition between generations, and now they are passing to Miss Chan.

l will be dead tomorrow.

I’ve known for several months that my life was coming to an end, and more recently I’ve been able to foresee the time and date. Tomorrow afternoon, a little after lunch. When Big Uncle died he wasn’t able to warn me about how my life would change, he had no way of knowing that I was the one who was going to take up the burden, but I have a little time left still. Perhaps in the remaining hours I can explain things to Miss Chan, tell her how it will be, offer words of advice. There was nobody to help me and there’s so much that I need to tell her. Perhaps one day she’ll also end up living in Coloane.

“Miss Chan, please, would you like to stay for dinner?”

About Graeme Hall

Graeme Hall is a novelist and short story writer. He has been a prize winner with the Black Pear Press short story competition and the Ilkley Literature Festival. His story "The Jade Monkey Laughs" won the English section of the 2017 Macau Literary Festival short story competition. Currently writing his second novel, Graeme also writes and blogs on music at: https://www.dongraeme.blogspot.co.uk/ Graeme lives in Yorkshire with his wife and a wooden dog.