You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The people on planet Krikkit are angry. They’ve just discovered they live in a universe. They’d never thought to ask themselves if they were alone but, now they know they’re not, it changes everything. They’re no longer those charming, delightful, intelligent (if whimsical), ordinary people of Krikkit. They’re manic xenophobes obsessed with obliterating all other life forms.

Ford Prefect, who’s one of those life forms, is convinced that Slartibartfast, Arthur Dent and he can never defeat such an enemy. The people of Krikkit are obsessed, but the three of them – especially Arthur – are just ‘dilettantes, eccentrics, layabouts, fartarounds if you like’. This lack of obsession is a deciding factor: ‘We can’t win against obsession. They care, we don’t. They win.’

So heartfelt is this passage that it’s tempting to think the author is talking to us through his character. Douglas Adams: obsessive or layabout? Fartaround or winner?

Frankly, Douglas was both. But who am I to say? I don’t have the authority of a literary critic or professional biographer. I have what some might think a far higher authority – I speak as a flatmate. Douglas and I knew each other as Cambridge students, but we weren’t close till we shared flats in Kingsdown Road, Holloway, and in Highbury New Park, at the time he wrote the Hitchhiker radio series and his first three books, of which Life, the Universe and Everything – where we meet the people of Krikkit – is the third. We shared two bathrooms, two kitchens, two living rooms, maybe a dozen romantic disappointments (and far fewer triumphs), a thousand LPs and a similar number of washing-up bowls.

My shared experiences were mortalised – I’d put it no stronger than that – in a Radio 4 programme with the T-shirtishtitle of ‘I Was Douglas Adams’ Flatmate’. So I feel I’m qualified to speculate about the man who was Douglas and to draw your attention to the evidence of his character in those pages.

Mind you, there’s something Pythonesque about a flat- mate stepping forward to analyse the character of a legend. (Hitler’s flatmate would doubtless complain that he kept annexing the yoghurts; Christ’s, that there were always twelve of his mates on the sofa.) So be it. Douglas was definitely obsessive and Python was the first obsession of which I became aware. At Cambridge, he announced he was going down to London to interview John Cleese for the student newspaper Varsity. His fellow students were appalled. This, after all, was the early seventies, that pre-Thatcher era in which farting around was the norm. If we had ambition, it was on strike or doing a three-day week. We lay about watching Monty Python. Douglas went out and met him. Wow, this Douglas man was a winner.

Cleese, along with Terry Jones and Graham Chapman (with whom Douglas co-wrote), became like creative elder siblings. Douglas craved their approval but, more than that, he emulated their conceptual leaps and verbal intensity. Consider Agrajag, a constantly reincarnated creature whose every life – be it as fly, rabbit, newt, oyster, flea, ant – is destroyed by Arthur Dent. Coincidence? Agrajag thinks not. Try reciting his rant in the outraged innocent tones of Michael Palin: ‘“That’s funny,” my spirit would say to itself as it winged its way back to the netherworld after another fruitless Dent-ended venture into the land of the living, “that man who just ran over me as I was hopping across the road to my favourite pond looked a little familiar . . .”’

Cleese was only the first famous person Douglas pursued, sometimes literally, because fame (his own and others’)unquestionably obsessed him. ‘I’ve just been to a party,’ he told me, in the living room of the Highbury flat, ‘and I saw a short, rather shy-looking man I recognised. So I followed him round the room and tapped him on the shoulder and said hello.’ Douglas paused and smiled, drinking in the wonderment of it all. ‘That man was George Harrison.’ Uncharitably, I thought of the diminutive guitarist’s apprehension as he was shoulder-stalked by the six-foot-five stranger. Harrison was just one of Douglas’s favourite Beatles. Ringo, in his opinion a shamefully underrated drummer, was another. John Lennon was the third – especially the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album. But I wouldn’t read beyond the first few pages of Life, the Universe and Everything if you’re Paul McCartney, not unless you enjoy sly jokes about your earning-power, made by one member of the Famous Club at the expense of another.

Python-obsessed, Beatle-obsessed, fame-obsessed: Douglas was all these things and less. There was a withdrawn side to his nature. Of course there was. How could he be a writer if there weren’t? Mostly, he withdrew to the bathroom. His baths were many and prolonged. Infinitely prolonged. We’re only four pages into the tale when Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged, pained by his own immortality, reflects that it’s Sunday afternoons he can’t cope with: ‘that terrible listlessness which starts to set in at about 2.55, when you know that you’ve had all the baths you can usefully have that day’. I know how he feels. Or, rather, I know how the guy waiting to use the bathroom feels. For years, I was that guy.

You can think of the Douglas who wrote this book as a two-headed man. There was a layabout head (let’s call it ‘Beeblebrox’) that was lost in space, the space inside that very head where the ideas came from; this head would sit on his body on the sofa in our living room while his hands expertly played guitar figures from ‘The Boxer’, Paul Simon being another of his musical obsessions. Beyond the guitar-playing, no action took place. In Slartibartfast’s phrase, Douglas was ‘struggling against something deeply insouciant in his nature’. When you spoke to Douglas in this mode, he took a while to respond. ‘Hello? Yes?’ he’d say, as if emerging from deep space in two stages. (‘“Arthur,” said Ford. “Hello? Yes?” said Arthur.’)

Then there was the ‘Zaphod’ head, the winner’s head, which was hugely and excitedly in the moment. It came towards you, its mouth pouring forth ideas and observations, frequently on the subject that obsessed him more than any other: new technology. The day he bought a cordless phone, Douglas went Zaphod on me for twenty-four hours. The phone was cordless, not mobile, and – this being the early eighties – it was the size of a training shoe. Nevertheless, it was new and it moved. All Douglas wanted to do that day was phone everyone he’d ever met, with the sole purpose of telling them he was speaking to them from a phone that could rove with him round our flat. For Douglas, the dawn of the cordless phone was as momentous as the coming of the talkies; the coming, if you like, of the walkie-talkies. Finally, after many calls, he worked out a way of breaking the news obliquely. On the phone to his umpteenth pal – probably a Python – he strode into his favourite room: the bathroom. There he proceeded to urinate from a great height, which was of course his own. Evidently, the pal asked what the noise was. Douglas explained, pseudo-casually, that he could now wee while talking on the phone because he owned a cordless.

Introvert, extrovert. Sofa-bound, manic. Fartaround, winner. Coming back to Life, the Universe and Everything after three decades away, I’m struck by the way it evokes Douglas’s flatmate rhythms. There are passages in the novelwhen we’re tootling down the motorway of the story, cruising at sixty miles per hour from one catastrophe to the next. Frankly, it’s all a bit routine. Then – whoa! – we’re not merely doing a hundred and twenty, we’re flying. By no coincidence, some of the most joyous passages in the novel are about the art of flying.

One problem is that you have to miss the ground accidentally. It’s no good deliberately intending to miss the ground because you won’t. You have to have your attention suddenly distracted by something else when you’re halfway there, so that you are no longer thinking about falling, or about the ground, or about how much it’s going to hurt if you fail to miss it.

Let us return to Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged. Bathed to hell, he searches for another way to cope with immortality. He plumps for a nap, possibly followed by a movie. So he asks his computer what ‘network areas’ they’re going to be passing through in the next few hours. ‘“Cosmovid, Thinkpix and Home Brain Box,” it said, and beeped.’

It’s extraordinary to find these names in a book first published in 1982, so redolent are they of Netflix, Lovefilm and the rest. With every passing year, Douglas seems to me more and more prescient, not so much a flatmate as a portal. Among the graduates I knew, he was the only one as well-versed in science and technology as the arts. That’s why he could marry science and comedy so brilliantly – he knew the bride and the groom.

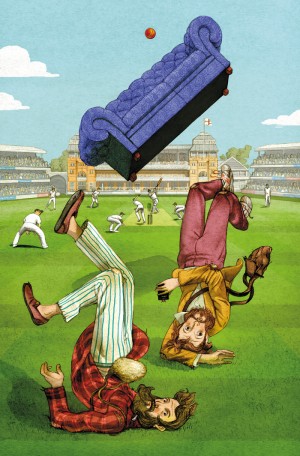

Of sport, though, he knew virtually nothing. Douglas spent none of his regrettably short life worrying about Arsenal, or the England rugby team, or how his horse was doing in the 3.30 at Kempton. (In the only sports-related conversation we had, he asked me why Henman had never won Wimbledon. I explained that our Tim could beat anyone in the world but he couldn’t do it seven times in a row. Douglas replied that he had ‘half that problem’: he couldn’t beat anyone in the world, but he could do it seven times in a row.) Hard as I try, I can’t forget the sight of Douglas kicking a ball about in Clissold Park, not so much un-coordinated as pre-coordinated, with a giant ostrich’s flair for receiving and distributing the ball. You can be certain that the cricket scenes so crucial to Life, the Universe and Everything aren’t based on personal experience, except those forced upon him by school sports teachers.

‘My capacity for happiness,’ Marvin says, ‘you could fit into a matchbox without taking out the matches first.’ This, too, is strictly non-autobiographical. Yes, there was gloom. Self-pity. Solipsism. But, overwhelmingly, Douglas was a benevolent man who was never not sentimental about his friends. Of the people who kicked a ball about with him that day in Stoke Newington, three are mentioned in these pages, for no other reason than that he liked them and thought they’d be amused. Brockian Ultra-Cricket – ‘rule one: Grow at least three extra legs. You won’t need them, but it keeps the crowds amused’ – is named in honour of Jonny Brock, one of the residents of the house in Islington where Douglas crashed, before he and I found a flat to share. I lived in that house too, as did a man called Paul Willcox. And there we are, in the Test Match commentary in Chapter 4: ‘Well, Peter, I think it was Canter facing Willcox coming up to bowl from the pavilion end . . .’ Are these references entirely indulgent, placed there to be understood only by his friends? Yes. Absolutely. That’s my point.

The sweet nature of Douglas is evident throughout Life, the Universe and Everything. Here’s Arthur Dent, recounting what is known in Hollywood as his character arc: ‘I have been blown up ridiculously often, shot at, insulted, regularly disintegrated, deprived of tea, and recently I crashed into a swamp and had to spend five years in a damp cave.’ All this, but somehow he’s never actually hurt. Though Monty Python and Kurt Vonnegut influenced Douglas’s work, I think of him more as a P. G. Wodehouse for the digital age. However alarming the situation Douglas contrives, he’ll always find space and time to be sublimely amusing. Witness Zaphod, moving through his spaceship in the dark, convinced he’s about to meet a terrifying intruder: ‘He inched his way up the corridor as if he would rather be yarding his way down it, which was true.’

Douglas: so long, and thanks for all the washing-up.

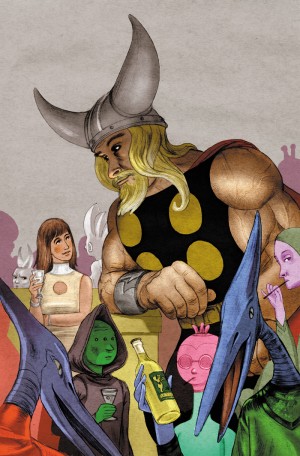

Life, the Universe and Everything, published by the Folio Society with an introduction by Jon Canter & illustrations by Jonathan Burton, is out now.

About Jon Canter

Jon Canter grew up in Golders Green. He studied law at Cambridge, where he was President of Footlights, before becoming a TV and radio scriptwriter. He also writes comment pieces for the Guardian. His first novel, Seeds of Greatness, was published in 2006 and chosen to be a Radio 4 Book at Bedtime. His third novel, Worth, came out in 2011.

Thank you! You pack a whole novel into a few paragraphs.