You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

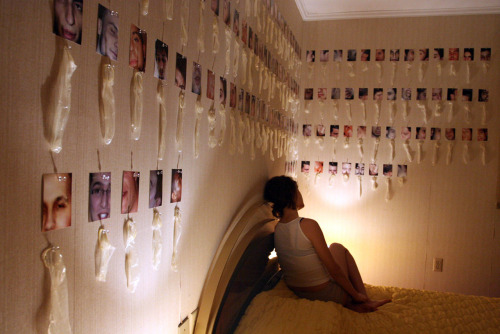

Go shoppingThe little wrappers appear then disappear, blue and yellow and green, glow-in-the-dark, medium, large, ribbed, edible: Paradise, Rough Rider, Kimono or Atlas, protections and projections blending myth and desire, all migrating into her underwear drawer from some far-off kingdom, then… to where? That’s the question, hovering between them, day-in and day-out: signs and wonders, portents of disaster, scattered traces of the invisible lives she slips into when out of sight.

Sarah has her virtues, but fidelity isn’t one of them, nor was it expected. Their contract encompasses different objectives. They’d once demurely called its territories ‘the soul’ but are now content with ‘companionship’, ‘partnership’ or even ‘last rites’.

It’s not that she is eager to hide them. She isn’t. But this simple act of putting them out of the way, in a place that he is barred from exploring, this uncomplicated secrecy is, for some reason, devastating. He feels cast aside and out of depth, as some of his poor undergraduate students must feel, floundering in the tempests of continental philosophy. The one who asked whether love exists, for instance, or if it is just another lie, one more in a series of deceptions that she hoped to outgrow eventually, shedding the skins of girlhood one strip at a time. And she’d asked this with such open-eyed seriousness: ‘Is there love?’ Then: ‘What does Deleuze say about love?’

‘What doesn’t he say?’ he’d replied, hopelessly. She held his gaze for a few seconds, daring him to move past affability, to evoke a world deeper than the surface options he’d always cherished, the ones requiring him to believe in nothing and delight in everything. He refused her at first, sensing his own weakness, but later made amends in a private setting. It seemed only fitting.

Love is a mixture of rapture and despair, he’d told her. It’s interpenetration, skin folding over skin, a dance of ecstasy and desolation. Love is a hand gripping the disembodied thigh of a character in a dream. He gripped her thigh. Love is an experiment, he said, an unsupervised examination. Total annihilation is its pass grade.

Tahir had used those lines before, but never so carelessly. He’d felt the need to save face, to redeem his inadequacies with excitement, to show he was still the master of worlds beyond her experience. But he was shaken to the core. His fingers were numb, his heart raced, his ears rang.

Is there love?

The question, like a weapon discharged over and again, each time louder than the last, circling and re-writing and dancing and swimming in his mind: a virus.

Is there, is there, is there love?

The simplicity of her interrogation unlocked his deepest anxiety. He envisioned the packets disappearing one-by-one, and each fading sheath reproached him like the punch line of the joke a student had once used, in an effort to provoke him:

Q: Why do black guys cry during sex?

A: Mace.

Tahir had laughed to prove himself beyond intimidation, before handing the monster a middling grade. Out of what? Fear? Disorientation? A refusal to be cowed?

The joke itself, he’d reasoned, was an incomparable essay, a sledgehammer aphorism of the highest order. But for years afterward, whenever he heard the word mace he froze, expecting to be hit by lightning, to be struck dumb or blind, for his eyes to burn and his nostrils to flame.

It’s true that humour has a way of disarming people, he reasoned, and humiliation is inherently humorous. Pain and pleasure coincide. One man’s joy is another’s disgrace. Nothing new in these realisations, of course, except his experience of them. The emotion behind the thought. His thick skin had begun to fray. Each worldly thrust produced a series of ruptures. His mind was no longer secure. The mask he wore barely cloaked his confusion. Tahir was growing old.

Another cliché: age is cruel and mocking.

It was easier in the early days. She’d come home smelling of cologne and sex, laugh loudly as she bumped into walls and doors, wake the kids to tell them she loved them, run a bath while singing Sugar Man by Sixto Rodriguez, thumping the water at the off-beat.

Every so often Tahir would lift his eyes from whatever book he was trembling over; in the early days, Cioran; in the middle period, Schopenhauer; more recently – as if to shield himself – Spinoza. Always with his brow furrowed, barely blinking, scouring each page for points of traction, ploughing the symbols for companionable roots and connections, all roads leading to his inner temple, a self-sufficient homeland of cerebral ecstasy. All of this, while she made do with garbos and solicitors in parking lots and serviced apartments. Or so he imagined.

Tahir was content to cast his own dim shadow over young and impressionable minds, meanwhile, and free-fall into numbed ataraxia: cigar poking out of his mouth, warm scotch coursing through his veins, a tangle of ideas merging and cross-pollinating then fading like the final quiver of a minor orgasm. A boy in his room playing with his mind. Glorified masturbation. This is what he’d dedicated his life to, while her flame leapt and glowed.

The night Tahir asked about the little packages, Sarah smiled, put aside her book, placed those silver-rimmed spectacles on the bedside table, inhaled deeply and said: ‘What do you want to know?’ He’d hoped to slip it into the conversation, a small observation about her four-nights-a-week, a hesitant grab at a loose thread on their tapestry of ‘safe’ discussion. He’d failed. She saw through his ploy and threatened checkmate. He backtracked and deflected. ‘Oh, nothing really. Was just making conversation.’

She stared him down, but he knew the victory would be short lived. No sense in letting it bother him now, after enduring for so long. Ten full years of inattentive patience. This dull-headed vigil; a degraded La Vita Nuova; his masterpiece of unconsummated love.

Marriage, for them both, had become endurance without contact, unity at a distance, coupling without intimacy. For her, a superannuated piece of folly and a game of why not. Yet, somehow, it had worked. Up to a point.

In the early days he made do with fantasy. He would lie in his bed at night and imagine that Sarah was off doing his bidding. In his mind, Tahir played the voyeuristic husband scrutinising animal jabs and growls from tinted windows, discrete cupboards or surveillance control rooms. He sent her away to trawl for other men to satisfy his own gargantuan appetite.

He was a pervert, a maniac, a sex tyrant.

But his performance in these roles lacked rigour. He was too much the participant; his imagination interrupted the scene. He’d thrust the bearish antagonist aside, reclaim the marital bed, bring order to the drama. And when the fantasy was over the real spectacle became all the more vivid: her absence, her coldness, the sweaty sheet, his pitiful state. Because that’s what her expression suggested, as she removed her glasses and sighed, daring him to challenge the long-established rituals: pity. He was to be pitied.

Tahir’s task, he’d once imagined, was to wait her out, to be the safety net, to endure each lash of the whip with measured sympathy. To abstain from resentful glances and unsympathetic remarks. To make do with the children. To be there when she emerged from her chemical stupor, no matter how long it took. To be present. Permanent. Meaningful. But when the children began school and the hardest phase was over, he finally understood. Her plunge into depression was long over. Seven years was enough to appease that despair. Those four nights each week were, in fact, an affirmation. It was how she came alive and it had nothing to do with him.

When he began wearing them again, years ago now, her eyes lit up. They’d just agreed that their second child was to be their last, and that their religious posturing, for his parents sake, was at an end. That night, she straddled Tahir in front of the mirror, then led him out onto the balcony, hitched up her skirt and leaned over the edge. It became their ritual. Public parks, train stations, libraries, cinemas, theatres and art galleries, but always at that micro-distance, the cold clarity of synthetic protection, the remoteness of performance.

For a while, Sarah even stayed home at night. They played games with the kids. He cooked meals. They had momentum. It lasted six months.

Then Tahir had an affair. It was his first in a decade, with a colleague from the research centre, and – unlike Sarah’s sojourns – it was a first-order betrayal, with dinners, holding hands, making promises and dreaming aloud. This was six months of deep and sustained passion, and Tahir grasped the source of his attachment only near the end.

She had let him cum inside her. It was as simple and as earth shaking as that. Instead of requiring performance – a plot to enact, levels of entanglement to wade through, a series of obstacles and constructed risks to overcome – she required nothing more than the simple, quivering deposit of his uncomplicated desire.

Instead of making up stories, or relying on invention to get them past the erotic finish line, they fucked. It was Tahir’s skin on hers, his body tightening against her thighs, his hands pressing her legs apart, his mouth sucking, their fingers burrowing, her nails on his back, his throat against her teeth, her sweat dripping on his chest, their intimacy leaking onto the bed sheets.

Is that love? Tahir wondered. Just… that?

And if it was love, what use was it to him?

The problem kept him awake at night. He became distant, irritable, mysteriously aggrieved, until, at last, he came to a decision.

There was little value in wild obsession, he told himself. Nor is there any future in it. Erotic passion was no more real than erotic disappointment. It was a trick perpetuated on the desperate; a plot designed to bring him down; a mythic deception on the margins of their marriage. No, the best Tahir could hope for, in the way of love, was the grudging affection that Sarah had readily granted.

He called off the affair and took a break from the research centre. Before long, Sarah’s little packets were summoned into action again, and her weekly rituals were re-established. This time, Tahir threw himself into Lacan. After all, he pondered, who are we to love?

About Shannon Burns

Shannon Burns is a writer, reviewer/critic and sometimes-academic, based in Adelaide, Australia. He has written for Australian Book Review, Sydney Review of Books and Music & Literature, and is a member of the J.M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. He won the 2009 Adelaide Review Prize for Short Fiction and the 2015 Salisbury Writers’ Festival Prize for Fiction. He is currently working on a biography of the writer, Gerald Murnane.