You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Eppur si muove

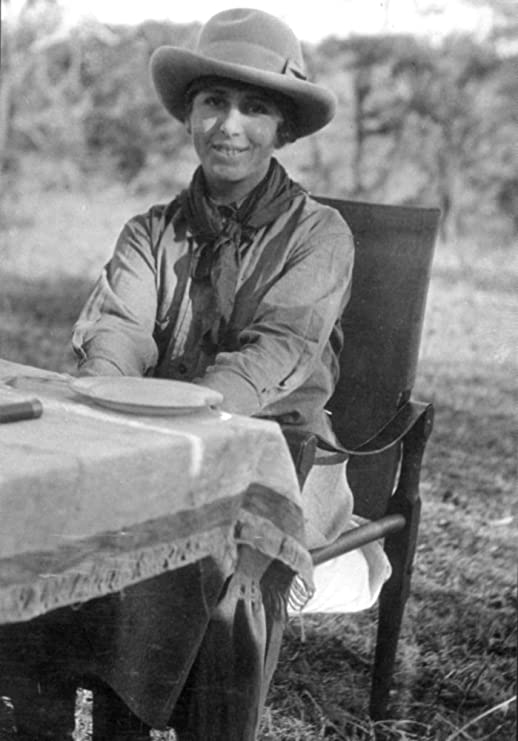

Of all the pictures of Isak Dinesen that I have seen, my favorite is the one reproduced in the 1992 Modern Library edition of Out of Africa. This is because of contrast. In many other photos, her smile is inclined, sometimes only a little, sometimes dramatically, tracing an ascending – at once ludic and painful – line. The angle of this gesture, I believe, became more pronounced with time, as if the upward compulsion of one corner of the mouth strived to compensate the immobility of the other. In the last years of her life, the result of this tension was striking.

I have seen this smile, or its inception, in people close to me, perhaps in the mirror as well. There is irony to it. Pain and the will, even perhaps the strength, to leave it behind – or below. Part of the soul is dead, a condition that finds its physical counterpart in what appears to be facial paralysis. A smile like this confuses because it’s crippled, the inanimate and the living phases of the same entity together. In reality, it is not a smile. It is only half a smile. And there are things in this world that cannot be thought of in halves: books, holes, rivers, happiness.

In the picture before me, however, Isak Dinesen smiles. The left corner of the mouth, yes, rises higher, revolving graciously, but this time the other side is not entirely left behind. Against a gravity that is visible even here, it goes up. Bluntly if not freely, the heavy part of her soul participates. And this is enough to nourish her countenance, to plenish it. In his Dizionario di filosofia, Nicola Abbagnano defined happiness as “a state of satisfaction due to the person’s own situation in the world.” In this safari photo, Dinesen is not exultant. Her general demeanor signals more a consistency than an effusion. She is, simply, satisfied.

What brought Dinesen to full life? Africa did. Or to elaborate on Abbagnano’s definition, Dinesen’s own situation in Africa did. There, in her farm, “at the foot of the Ngong Hills,” she found her place on Earth.

Book of complaints

It is enough to read a hundred pages into Dinesen’s masterpiece, or to skim a random selection of the numerous letters she wrote from her bungalow in the course of seventeen years, or to conjure the temptation, always easy, of romanticizing something like a long stay in a remote, “natural” continent a century ago – it is enough having lived, perhaps – to understand that her time in Africa was far from idyllic.

Born on April 17, 1885, in Rungsted, Denmark, her name was Karen Dinesen (Isak Dinesen is one of several literary pseudonyms; Baroness von Blixen-Finecke, the name she acquired by marriage). On December 1912, she got engaged. The restraints she felt among her family – worsened after her father, a liberating force of sorts, took his own life in 1900 – coupled with the need break the dependent bond she had with Mohder, as well as a thirst for adventure, moved Karen to seek a future in a faraway country. She persuaded her fiancé and plans were made. Karen and Baron Bror Blixen-Finecke arrived in Mombasa on January 1914. They married there.

The collection of misfortunes that Africa, from a certain point of view, represented for Dinesen began immediately. In 1914, only a few months after her arrival in M’Bagathi – the farm near Nairobi that Bror would run – she was diagnosed with syphilis, a condition that forced her back to Denmark a year later to get specialized treatment. Various sources argue that she contracted the disease from her husband. The prologue to the Modern Library edition of Out of Africa cites her saying: “There are two things you can do in such a situation: shoot the man or accept it.” As a consequence of the initial mercury treatment she received in Africa, she would suffer attacks of severe pain for the rest of her life.

That same year, after the outbreak of World War I, she and Bror Blixen were accused of helping the German army and, rejected by the society of European settlers (the “Colony,” as she puts it), went through a period of dire isolation. Although apparently tolerable when it occurred, this isolation became for Dinesen a sort of trauma. She recalls in her memoir: “At the time, I had taken [it] lightly, for I was not in the least pro-German. …it must have gone deeper with me than I knew of, and for many years after, when I was very tired or when I had a high temperature, the feeling of it would come back.”

Her marriage, never sound, collapsed in Africa, where it had started. It was doomed, perhaps, from the beginning. Bror was her second cousin and the twin brother of the man she had been madly but painfully in love with not long before her engagement in 1912. Based on Judith Thurman’s unmatched biography (Isak Dinesen: The life of a Storyteller), Robert Langbaum wrote for The New Criterion that “…she settled for the slightly less good-looking and dashing Baron Bror…” The nobleman, moreover, never took much interest in the relationship. A “promiscuous animal,” as Langbaum calls him, and a lousy farm manager, he disregarded Karen for other women and neglected the farm for other, more stimulating, enterprises, mainly the safaris he conducted. She became romantically involved with Denys Finch Hatton long before the divorce, perhaps as early as 1917. “The two men were friends, and Bror would introduce Denys proudly as ‘my wife’s lover.’” And yet, when the marriage staggered and eventually collapsed, Dinesen tried to hold on to Bror. They remained friends long after the separation.

The end of one relationship didn’t bring stability to the other. She and Denys had been lovers – not a couple – and they remained lovers: the randomness and the risk of adventure continued. In Out of Africa, she sums up the romance under section III, “Visitors to the farm.” That is what Denys was, an intermittent presence. Although Karen’s house was his only fixed station in Kenya and he kept his library there, he stayed with her “for brief periods between trips to England and the safaris which he ran as a professional hunter.” Sentiments do not follow in the footsteps of ideas. Dinesen tried to come to terms with Denys’s elusiveness, but her own expectations wouldn’t let her. On the one hand, her intellect sought to detach the feeling of love from the need to own. Or in Judith Thurman’s words: “To run parallel with her lover, a friend, but not a possession or a sexual object, those were the conclusions of Karen Blixen’s soul searching.” On the other, the compulsion to keep him, her desire for a secure companionship, rose above her ideas and took charge. “She is trying to take possession” of him, said a relative of Denys in 1929. “It won’t work.” It didn’t. The more she tried to retain him, the more a self-centered personality like his resisted. “I will never come for pity,” he said once to Dinesen, quoting Shelley, “I will come for pleasure.”

Dinesen suffered a double loss. First, the lover faded away. “During her last year in Africa,” Langbaum recalls, “when it became clear that she would have to sell the farm and return to Denmark, Denys’s ‘detachment was absolute.’” Then, as he flew his private airplane from Mombasa to Voi, he was killed in an accident. Dinesen expected him back on a Thursday of May 1931. “…he would fly from Voi at sunrise and be two hours on the way to Ngong. But when he did not come, and I found that I had things to do in Nairobi, I drove in to town. …There was, somehow, a deep sadness over the town, and over the people I met, and in the midst of it everybody was turning away from me.” After luncheon, “Lady McMillan asked me to come with her into her small sitting-room, and there told me that there had been an accident at Voi. Denys had capsized with his machine, and had been killed in the fall. It was then as I had thought: at the sound of Denys’s name even, truth was revealed, and I knew and understood everything.”

Dinesen’s home in Africa and the only real constant in her life there besides Africa itself, the farm – not M’Bagathi but a larger one, M’Bogani, bought in 1916 by the Karen Coffee Company Ltd., which belonged to her maternal family – far from growing into the profitable business the investors had envisioned, turned out to be a bottomless pit. The farm was decimated by droughts, fires, plagues, and sudden falls in the international price of commodities. Baron Bror’s disdain for management didn’t help either. But like Karen’s marriage, perhaps the fate of the farm was written from the beginning. The land was “a little too high up for growing coffee. …The [cold] wind blew in from the plains, and even in good years we never got the same yield of coffee to the acre as the people in the lower districts of Thika and Kiambu, on four thousand feet. We were short in rain, as well, in the Ngong country. …It is a heavy burden to carry a farm on you.” In 1920 and 1921, respectively, her brother Thomas Dinesen and Aage Westenholz, her uncle and chairman of the company, travelled to Kenya to assess the situation of the farm. As a result, Bror Blixen was dismissed, and Karen was given full authority, as long as Bror kept entirely out of the management. This is when the marriage ended. Thomas remained in Kenya for almost 28 months. He left the farm convinced that it had no future. What followed were years of long agony for M’Bogani and, in a sense, for Dinesen herself, as she witnessed her telluric bond with Africa become gradually weaker. She “thought up many devices for the salvation of the farm”: growing flax, manuring the fields, “keeping cattle and running a diary,” etc., but none of these experiments worked. “When I had no more money, and could not make things pay, I had to sell the farm. A big Company in Nairobi bought it.” Dinesen stayed in M’Bogani, no longer hers, for another eight months, until August 1931, to look after the last harvest, secure the future of her African workers, and hand over the property. “I was the last person to realize that I was going.”

My heart’s land

The other side of the coin was, of course, her love for Africa. What made up for misfortune and somehow gave meaning to it was her bond with the place and its people. Difficulties were the price she had to pay to be where she wanted to be and lead the life she desired. Africa was the substance. All other things, no matter how seemingly important, were accidents. Even Denys she could not take seriously; with Africa and her “black brother” it was “something quite different,” as she wrote in a letter, a “matter of life and death.” While Denys, the colony, and her family in Europe ran on a parallel track, close perhaps but separate, Africa ran through her, like blood. It carried nutrients, oxygen. It meant life to Dinesen. At the foot of the Ngong hills, almost forty-five hundred miles away from her birthplace, she breathed in a secret vitality. She had been, in a way, half dead. In Africa she awoke to full life.

Her assimilation to Africa was so immediate, so positive and complete, that Dinesen attributed it to an inherent, congenital inclination. “If a person with an inborn sympathy for animals,” she elaborates in her memoir, “had grown in a milieu where there were no animals, and had come into contact with animals late in life; or if a person with an instinctive taste for woods and forest had entered a forest for the first time at the age of twenty; or if some one with an ear for music had happened to hear music for the first time when he was already grown up; their cases might have been similar to mine.” In Africa, Dinesen found her habitat, her natural environment. Or to put in other words, she reached home. Writer Sirkka Heiskanen-Mäkelä speaks of a return, Dinesen’s regressus ad originem. Susan Hardy, of the Ngong country as “the place for which she had felt ‘homesick’ all her life.”

Sailing into Africa, sailing “straight into life,” as she put it in an essay, meant in this sense not a journey but a time of reintegration. Africa was the womb, the transposition and thus the continuation of the simple, stable, nurturing mother. The Kikuyu, the Masai, the Africans in general, just like she said, her brothers. Connected to the place as though through an umbilical cord, whatever occurred in the geography reflected in her. There were no clear boundaries. She was part of the landscape, and the drought was always in her “like a fever, and the flowering of the plain like a frock.” She belonged to Africa. This is why those early words in her book of memoirs – perhaps the most important words, perhaps the most beautiful – resound so potent and clear, like a solid bell above those “immensely wide views,” like a self-evident truth or an axiom: “Up in the high air you breathed easily, drawing in a vital assurance and lightness of heart. In the highlands you woke up in the morning and thought: Here I am, where I ought to be.”

When Dinesen lost the farm, losing thus her main connection to the country, she stopped feeling alive. She remained in Africa and in M’Bogani for another eight months or so, but the “attitude of the landscape towards” her had transformed. “The hills, the forests, plains and rivers, the wind, all knew that we were to part.” The same day she signed away the property, “the country disengaged itself” from her, “and stood back a little.” Africa, the fertile soil, the locus of well-being, a vital organ for Karen, had retreated, had withdrawn enough to say: “I am no longer yours.” Spatially, Dinesen and Africa were still together. Sensitively, however, they had taken separate ways. This, I believe, put Dinesen in a state of dissociation: being and vitality no longer unified but segregated. She went on with her existence, she carried out her duties, but she was again lifeless. Things were happening to her, and she “felt them happening, but except for this one fact,” she had “no connection with them, and no key to the cause or meaning of them. …Those who have been through such events can, in a way, say that they have been through death – a passage outside the range of imagination, but within the range of experience.”

Dinesen’s “death” was in a way the logical extremity of a time marked by misfortune. During her years in Africa, Dinesen lost her good health, her marriage, Denys Finch Hatton, many a friend, the garden by the river, all her money and possessions, the old Kikuyu women, the Ngong hills, M’Bogani. At the end, all there was left for her to lose was her own self, and she lost it. “…by the time that I had nothing … I myself was the lightest thing of all, for fate to get rid of.” But her “death” at the same time is the tragic demonstration of a long fall and therefore of the great heights she had reached – vitality and plenitude. When at last, on August 19, 1931, she sailed away from Africa, she sailed away from life. She quit Africa with nothing, yet Africa had given her everything.

Ex Africa

Out of Africa is a work of admiration. It is Isak Dinesen in the midst of the Ngong country looking upon it all – the sublime and the terrible, the organic and the mineral, the simple and the mysterious – devoutly. It is the landscape breathing life into her, and her thanking the landscape. In writing this volume, Dinesen’s only purpose was to talk of her Africa – a beloved, lost Africa. That is why the focus of her attention in both the opening and the final pages is the farm and Ngong, the hills, the natives. That is why she leaves out or reduces to a minimum every foreign element, no matter how active they were in her African life – she mentions Bror only once, and not even by his name; she obviates Thomas Dinesen, her brother, who spent two years in the farm and got her through dire times; she makes no reference to her mother and her visits; she writes fondly of her European friends but as such, as alien graces. Denys is an exception, “but then Denys is like her,” in Langbaum words, “he … stands in the same relation to Africa as she does.” Like Dinesen, he has been domesticated and he is therefore not a foreigner anymore. The writer, moreover, needed Finch Hatton to have literary weight. Only in this way could she use the narrative of his death – like that of Kinanjui – in the final part of the book to build toward the fundamental tragedy: her parting from Africa. Calamity is the last seal of glory. To depict the width and the nobility of her Africa, Dinesen had to convey the magnitude of the fall. As Langbaum says, she concentrated “all the trouble at the end, so that the loss of the farm” came “through as the loss of Eden.”

If Out of Africa were

a painting, it would belong to the particular genre of “Landscapes with farm

and woman.” The immensely wide views, the trees growing in horizontal layers,

the colors of pottery, and the chief feature – air – would occupy, of course,

the entire panorama.[1]

To the West of the hills, there would expand a lively, capricious yet giving farmland

– the able artist would have no trouble mastering this conflict. In the center

of the canvas, a stone’s throw away from us, the likeness of Dinesen is

immediate but nevertheless subsidiary. This occurs because, facing the observer

full-length, her countenance is yet another African effusion. In her eyes as in

the fur of the beasts, Africa surfaces; through them as through the dark

parabola of foliage, Africa spills itself. And yes, Dinesen smiles. The right

corner of her mouth is normally stiff – perhaps atrophied by sorrow – even when

she feigns contentment. But in this piece of art the entire landscape – the

blind fauna and the widespread vegetation, the sown fields, coffee perhaps, the

far shepherd, the blue back of the Ngong hills, the oncoming dusk – takes

possession of Dinesen and she has no alternative but to live. You can see the

tremendous weight history can concentrate in an area as small as the right side

of a face, the heaviness is there, but Africa, with two black, motherly

fingers, picks it up. And Dinesen’s lips blossom. The big canvas bears witness

to it – she is right where she ought to be.

[1] I paraphrase Dinesen in this sentence and in the last one, Out of Africa.

Ignacio Ortiz Monasterio

Ignacio Ortiz Monasterio (Mexico City) is the author of two books, Compás de cuatro tiempos (2015) and Anatomía de La feria (2018). His essays and stories have appeared in The Southern Literary Journal, Mayday and Spanish-language magazines like Este País, Nexos, Luvina and Letras Libres. He received a Fulbright grant to attend Emerson College’s writing and publishing program.

- Web |

- More Posts(2)