You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

After the meeting in the pub ended, they stayed sitting in the dark. We waited outside. Here in the little country, the ache of winter crawled down to our bones. The seahorses looked tired as they queued to give their biometrics. Their bodies, faded by the latest round of tests on their reproductive pouches, looked like old silk. There were others in the pub; others who weren’t in the meeting, or for it. Some of us were nervous. The last meeting a fortnight ago had ended abruptly because a protester had stormed in high on E, screaming at the seahorses.

‘Face slashed by fins,’ I told Sara at the park later. It had taken us a while to beat past the pulsing bodies of the seahorses and get to the protester. Some seahorses began whipping their fins, furiously changing colour, clouding over her and crowding me and the other women out, till all I could see through their bobbing skins, from right at the back, was her body as a hazy, dark blob.

‘What happened to the protester then,’ Sara asked, chewing on a bit of stick I found at the entrance of the park.

‘A&E. She called them sinks.’

Sara swore loudly.

This meeting did not end like that one did. I watched, with other humans, as a stream of gelatinous, life-size seahorses bobbed out, coats, fins and all. Jahan was the last to appear from the pub. ‘I hate pressing my finger against that thing,’ he said, holding up a glassy-looking finger.

We walked in silence, until we crossed the clinic where I had my first abortion.

‘It’s still there,’ I said.

‘You can still go in,’ Jahan remarked.

We stopped at the supermarket near our home. He looked at me from the rows of tinned beans and said, ‘I’ve decided about termination.’

I saw a woman in the cereal aisle stoop to pick up a box. Probably eavesdropping.

‘Might sing at the gathering tomorrow,’ Jahan said, sitting on the curl of his tail. ‘Will you come?’

Why seahorses, some of us had asked our parents when we were old enough to know that our history textbooks made no mention of our friends. No one could answer us, although the scientists tried. Ultrasounds had indicated nothing unusual other than a weak heartbeat, and several new human mothers had remained unconscious for days after a single glance at the creature that dripped from their vagina. Those with a sense of history had found some humour in the fact that the seahorses being born were all male. Seahorses with light, fleshy arms. Life-size seahorses, with a bafflingly, structurally sound vertebrate system that allowed them to bounce high on their tails. Baby boy seahorses turning one, two, what was their lifespan again, teenage seahorses hooking up with humans at school, seahorses arguing with their parents about being old enough to drink and vote, the rings on their trunks widening while ministers furiously revised immigration laws whenever they took breaks from reassuring humans reading papers that their jobs would be safe. Debates were raged over terms like “mixed-species.” Lawyers took on protection cases at hospitals. Long-form essays were written about the anthropocene and climate change, the missing gills, the startling vocal cords—and the seahorses kept coming, whipping their fins, changing colour, singing.

The first generation of seahorses, once old enough, were happy to contribute to these discussions. Their deep melodic voices rang across the internet and radio stations, perfectly coherent in languages already comprehensible to humans. On summer evenings, seahorses across the country gathered at parks and pubs and sang, their snouts and throats quivering in clear air as though the earth were lifting itself. We put our phones away and listened. Tears were easy, and recruitment to the churches remained hard. But the seahorses stayed singing. The air sweetened. Trees stirred. An ancient thrill was returned to the little country.

I was mid-nosebleed, aged fourteen, when I heard a seahorse choir sing. I looked out of my bedroom window and saw them bobbing in the courtyard outside the flats, belting notes as clear and curved as their spines, wishing a safety spell on everyone listening. The music, I was certain, returned a few years of life to us. Heads at windows. Breaths held like we were all underwater.

It’s been like that since. Every time the seahorses sing anywhere. It’s how they have their way.

Jahan says he saw me before I saw him. It is difficult to dispute him when he gets like this, because a big part of our shared history consists of letting such declarations sediment. At school, I saw the back of his iron-dark hair, hair inherited from his Iranian mother that cascaded into uneven angles down his long, ribbed back. He was paler than the other seahorses. When he spoke, I felt like I was listening from the inside of a dollop of honey.

We became friends on the playground—this we agree on—as I was helping him on to the swing. He caught me staring at the long, dark glitter of his mouth.

‘If you hold my tail,’ he said. ‘We’re okay.’

We couldn’t have seen it then. The years tumbled into one another. I taught him how to ride on the new seahorse cycles. He made me seaweed cakes using a recipe that his academic parents wrote up. He was in a band, he said, and always apologised after he said so. I learnt Tamil so I could talk to my grandmother and watched as the thin lines on Jahan’s skin darkened into an irreducible pattern. We got our first phones and eventually learned each other’s lock codes. Abortion for seahorses remained illegal. ‘Dating your brethren yet,’ I would joke on the phone. He never laughed, and he never answered. When the second wave of anti-seahorse rioting happened in the mid-noughties, I called him after midnight from my university halls and said I loved him.

‘I know,’ he said.

‘I don’t want kids,’ I replied. ‘And housework 50/50.’

‘Deal,’ he said. I could hear him smiling.

‘You okay?’ I asked after a pause. The TV was on at both ends of the line.

‘I am now,’ he said.

That night, the world spun out of order. The next morning, Jahan drove up with a box of seaweed cake. I had never kissed him before, but it felt like we had done this ridiculous tender dance all our lives, snout to lip, his soft, bulging torso brushing its way up my thigh, his shudders of pleasure when I stroked the lichen-like ridges on his chest. When he flicked his tail inside me, I came, again and again. It was the best sex of my life.

Sunlight patched its way through my room, climbing the delicate dark rose lines on Jahan’s neck. I felt like I was with someone else who wasn’t Jahan, Jahan my childhood friend, the singer-lawyer who went through puberty kinder than anyone I knew, Jahan whom I wanted to call after this angelic soft-haired seahorse who lay next to me left my room.

‘I’m your first seahorse, aren’t I,’ he said. He pulled my hands up in his palms. Their clamminess sunk my fingers in and warmed them.

‘Shut up,’ I said.

Five years later, we were married in his parents’ garden. He wore a black sherwani, and I wore a yellow sari. His fin shimmered. When he sang, our fathers cried. In his vows, he talked about how important it was for him as a seahorse to be held.

It was a bad economy for having kids anyway, but I thought he didn’t want one either. Then one night at a friend’s party, Jahan said something like, having kids has always been a way for seahorses to feel equal to humans. I rolled my eyes, then looked at him. ‘Later,’ he said, fingering the leaf of a money plant cascading from a bookshelf. Through his translucent fingers, I saw the green congeal.

We didn’t talk about it on the tube home, but a week later, after two bottles of shiraz, we volleyed our way into it.

‘Are you sure you’re the type,’ I said.

‘Would you say that to another woman,’ he said.

‘You’re not allowed abortions anyway,’ I said.

‘Listen to yourself,’ he said.

The conversation ended when I saw copper flecking the sky. I love you. Don’t leave me. I love you. We had bright, angry sex, over and over. Our words came out hard, and we stoked them with fear.

Down in the ocean which flotsamed from the river outside our home, Jahan’s ancestors, unsuspecting, still the size of an infant’s finger, swam in a shoal across the depths of the map, past bushes of corals resembling fires, tying and freeing themselves from the edges of reefs. Millions of fry wiggled their way out of their fathers, never to meet again. How little it takes to untether a life. How much more it takes to keep one going.

And then it began. There were reports of a sixteen-year-old seahorse in a youth choir collapsing after he bled through his robes. A miscarriage after an hour of choir singing. We saw videos of underground seahorse groups having abortions after breaking into song. I particularly liked one where five pregnant seahorses sang a section from Mozart’s Requiem around a kitchen table, and three of them bled in succession.

The following days stuck to one another. The tabloids were hysteric. Human genocide! The headlines blared. A group of seahorse activists had staged another protest and been teargassed. Seahorse-only prisons, a sitting MP suggested. Jahan and I started to go for the meetings, but the incident with the protester at the pub meeting stirred a growing consensus in the little country that the seahorses were a threat to the human population. Jahan only left the house for the pub meetings now, where his ID was checked along with those of other seahorses. The state said that group singing was dangerous, and outlawed seahorse singing in public.

‘We’re going to need to do something soon,’ I said to Jahan, the night before a pub meeting. ‘Unless you want to keep it.’

Jahan was pregnant. He didn’t want to keep it this time. But he said he didn’t know about next time. I said I did know about next time. We didn’t know the future for us, but we heard music around us, every day. Meanwhile, a national register of seahorses was being drawn up, using their fingerprints.

‘We may have news at the meeting tomorrow,’ said Jahan, ignoring my last sentence.

The day after the meeting, when Jahan asked me in the supermarket if I’d go with him to the gathering where he was thinking of singing, I said yes.

‘Good,’ he said. ‘Parties are no fun without us.’

Sara gives us the address on an encrypted messaging app and tells us to get there for dusk. We leave the house before curfew starts, and I tighten the belts on our coats before we enter the tube station, hiding the sparkle of my shirt, and the bright pink velvet of his jacket.

‘This is unnecessary,’ Jahan says.

‘Can’t look like we’re out celebrating,’ I reply.

The tube is mostly empty. We alight two stops after Baker Street and make our way to the address. Outside the door, a tall figure awaits. As we stride with our anonymous escort, the streetlights blink into little bright bowls for the evening. We are headed for the park.

‘These parks are on surveillance,’ I say. My voice is very dry. Jahan is quiet.

‘We’ve bought ourselves some time,’ our escort replies. ‘Hurry.’

We enter through a side-gate and walk for another fifteen minutes.

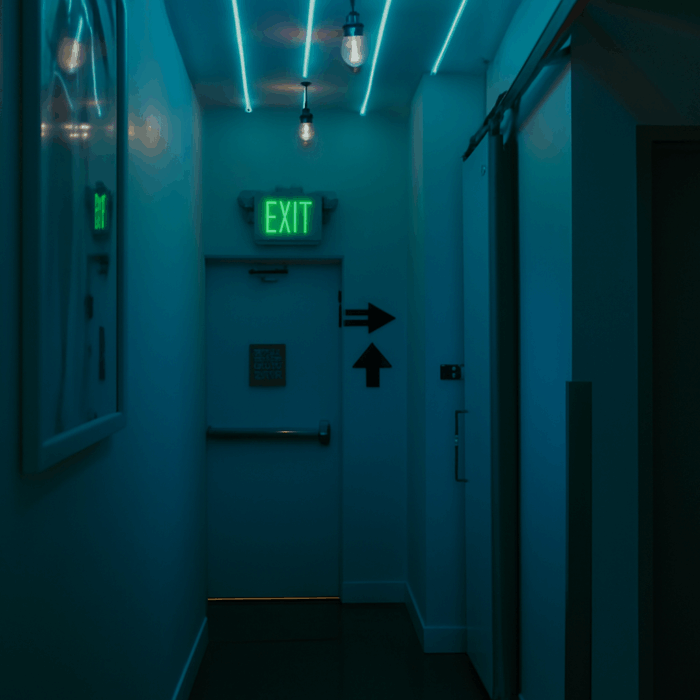

And then singing so sudden, we must have crossed a world. Another begins in the length of a blink. A bejewelled evening. Electric paper lanterns on the grass. Children perched on trees. Families around picnic baskets. Smothered giggles. The music escalates as we walk towards it.

Jahan has slowed to a bounce. ‘Rafi sa’ab,’ he says.

‘Do you have a programme?’ asks a seahorse with a face tattoo.

Harmonies hang in the air. More chatter. Towels being passed around as smaller groups sing amongst themselves. We are given the score. A section of Handel’s Messiah, by the Seahorse Philharmonic, who are seeking donations to pay house-visits and speed-train doulas. The latest music. Top ten. Gospel music. Classic rock. Bollywood. Palestinian hip-hop. Medieval music. Urdu ghazals. Soul.

Jahan is watching a group sing the latest pop single from a Canadian artist.

‘They’re not bad,’ he says a minute later.

‘Does it matter?’

‘We don’t really know,’ says our friend Amery, who appears, clutching a bag and a rose, swishing his turquoise tail. I hug him. He kisses the top of my head. ‘We’ve got singers moving around groups, keeping them in tune. Just in case,’ he says.

‘I’m three months in,’ observes a seahorse with a bulging pouch, who has been listening. ‘I know what I want to sing.’

‘Three trees down,’ says Amery, handing him a blue towel and a bottle of water. ‘You should start bleeding within minutes of singing. There’s help around. Enjoy yourself,’ he calls after the seahorse.

We watch the seahorse glide towards his tree.

Amery turns to Jahan. ‘Ready,’ he asks softly.

Seahorses do not mate for life. They mate for as long as they are held. We are the same. I am the same. Every seahorse dazzling to their fullest height, their vocal cords singeing the ache into debris. Contrapuntal echoes. Voice suspending time. Impulses stacking note after note, as the towels on the grass clot red. A union holier than anything familiar, anything ever paired in the history of loneliness. A new people coming to be. The sky scales its eyes back, and the last thing we see before the darkness drops, is the folding of a chord.

By Sharanya Murali