You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

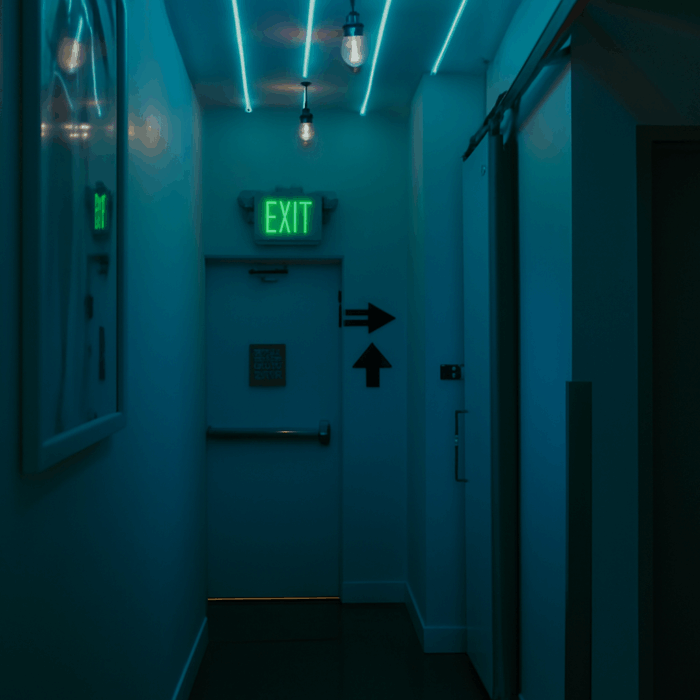

You must run, little man. Run as fast as you can down the steps and across the dusty square of the front garden and out onto the street. Run as fast as you can and don’t look back.

Don’t waste time dwelling on why you can’t think of one good reason to stay. Why your mum never seemed to like you. Why all the other eleven-year-old kids got hugged by their mothers. Just run, head down, and keep going.

Run down the street where you first learned to ride a bike. Where you and Tyler from the house across the street played in the go-cart his dad had built. Where the go-cart picked up speed as the hill falls away. Where the front wheels started wobbling and where you hit the curb and broke your leg. Where your mum suddenly appeared and even though you were all busted up, in agony you remember, blood in the gutter, a tooth missing, you thought she might hit you. Run.

You must run, as fast as you can, the same way the ambulance went after you’d been scooped up off the street. Keep going at the give way sign. They never put the siren on and although you were hurting from the broken bone, and the sight of your mother, hands on hips at the ambulance door, you remember wishing they had. You wanted the flashing lights and all the noise and fuss and attention that you thought you deserved. A small reward for the pain in your leg and in your heart, another tiny slice taken from it.

Head down, keeping running. Where the street flattens out and runs dead straight between two rows of tatty houses, set back from dried out rectangles of brown grass. Run like your life depends on it. Like she’s hot on your heels, right behind you, her eyes red and crazy like you have no idea what she might do next. Or like she hasn’t even noticed. Like she’s sitting in the back garden with your baby half-sister, smoking a cigarette, an empty beer bottle held idly in one hand.

Past Saint Anne’s School where she told you to make friends and when you did, she ordered you to make other ones. Friends who were polite and called her Mrs Ryan and rode bikes out to the country park to eat the sandwiches their mothers had made. You must run, fast and determined, past the school, shut today because it’s the weekend and all the other year six kids are with their mums and dads at the shopping centre or the cinema or up at the lake.

Run, little man. Past the house where Marjorie lives with her dad. Where you learned about the difference between boys and girls and where you kissed that one time and where you wished you kissed again. Marjorie who knows everything about cars and motorbikes and swear words and body parts. Who’s three years older than you and rides you down the street on the handlebars of her dead brother’s bike. Who showed you how to get up on the roof of the supermarket to watch the fireworks and drink beer with her brother’s friends. Who let you fall asleep in her lap while she smoked weed and who’d carried you home and laid you down in your bed without your mother even noticing. Run.

Over the tracks where Karl had shown you how to flatten a pound coin on the rail. Where you’d hidden in the bushes until the huge engine had passed, its horn so loud it made your skinny ribs vibrate. Karl who’d been your best friend, whose parents had taken you to a restaurant for his birthday, who you’d been bowling with. Who your mother said you shouldn’t see again after she’d turned up drunk at his house to pick you up. Whose parents’ lawn she’d driven across, right through the sprinkler, leaving deep ruts where she spun the wheels on the wet grass.

Run on down Quarry Hill, past the cemetery full of people you don’t know. Neat lines of graves bleached white in the stillness of the afternoon. Past other peoples’ friends and relatives. Maybe Marjorie’s brother, who died in Afghanistan, although you never asked where he’s buried, how much of him came home. And not your dad, nor your grandfathers nor your grandmothers, your aunts and uncles. They’re not dead, they’re just not here. Although you have no idea, really.

Don’t think about them now. Just keep running. Your lungs hurt, all hot and wet, and cold too, like the metal handrail at school that time it snowed, but don’t look back. Keep going, as fast as you can. Use everything you’ve got and run, run, run.

There’s the old signal box. The hours you spent up there last summer while your mum was at work. The view up and down the tracks. That thrill when you heard the distant horn rolling across the fields. And then the light of the diesel engine through the shimmer of the heat. A pinprick in the haze and then the outline of the train and then the clanging bells of the level crossing and the vibration in the rails. You pulled the levers even though you knew they did nothing and for a minute or two while the engine thundered past, its long line of freight wagons clanking over the points, you felt like a king. Like someone special.

That was then. Years and months and weeks ago. And yesterday too but now, little man, you must run. Keep running as fast as you can. Until your legs give up. Until your lungs feel so stretched they might pop like a birthday balloon. Until they can’t take it anymore.

There’s sweat in your eyes, your hair. The buzzcut that Marjorie gave you, that your mother said she hated, that made her lash out wildly, her eyes on fire with drink, has grown. Your hair lank, unwashed, uncared for, hot and wet against your neck. Keep going.

The pavement is wide and empty here and you must keep running. There’s the vet’s and the fried chicken shop, a store that sells electric wheelchairs and a rundown pub that your lying mum says she’s never been in. Then a row of boarded up shops and the old cinema that Karl said he’d broken into once although you’re not sure you believe him either. Run past the off licence, the bank, the charity shop where your mum told you to go and find a jumper last winter, five one-pound coins gripped tight in your fist like they were gold, like they were all you had in the world.

Keep your head down and keep pushing on, across the lights, past the church, and then the park where that creepy guy your mum was going out with took you to kick a ball around that one time. It was like he was trying to be your dad and then your mum threw him out because of something to do with money and his brother and some plan they had to rob a petrol station.

You must run. Past the ruined factory where they used to make furniture before everything came from Sweden and China and every other place. Where those guys with the dead eyes sit round and leave plastic needles and empty cans. Next to the wall that says there is no future in red and blue graffiti and is signed by Wez who Karl thinks might be one of the older kids who got him into the abandoned Ritzy that time.

Run little man. Out past the old steelworks and the chain-link fence that seems to go on for miles and the dogs that guard it day and night.

Your feet hurt like hell. The soles of your Converse are worn, the big toe on the left has broken through the rubber. Keep going and don’t look back. It’s a mile to the country park and there’s nothing on the road. Just an eleven-year-old boy with eighty pounds in his jeans pocket. All you could find, an afterthought as you passed your mum’s handbag hanging from the hook by the front door. You didn’t know you were going until you were gone and now you can’t stop.

You can’t stop now. You’re nearly there.

You must keep running. Away from the town you’ve only just realized is small and shitty. Away from your baby half-sister whose future you mustn’t think about too hard. Away from the shouting and the doors slamming and the sound of your mum screaming drunk in the next-door room.

You must run, little man. All the way past the turn off that marks the edge of the park. The walls of pine closing in like a friendly hand around an injured bird. Past the burnt-out car and onto the dirt track that carves its way into the woods. Keep running.

Past the spot where Karl had a birthday barbeque that you weren’t allowed to go to for reasons that were never clear. The tracks that finger their way deep into the endless world of trees and leaves. That fan out for further than you’ve ever been. That feel like a gift, a friend, the familiar dark beneath the forever canopy, the deep rich fug of loam. Deer and squirrel and rabbit. Blackbird, goshawk and kite. And you, little man. Home at last. Hands on knees, bent double, your lungs screaming for air.

Into the forest you go. Gone. Forever.

By David Micklem

David Micklem is a writer and theatre producer. He’s recently been published by The London Magazine, La Piccioletta Barca, Litro, STORGY Magazine, Scratch Books, the Cardiff Review, Lunate, Bandit and Tiger Shark. He’s been shortlisted for the 2023 and 2021 Brick Lane Bookshop Short Story Prizes, the 2023 London Independent Short Story Prize, the 2022 Bristol Prize, and the 2020 Fish Short Story Prize. He lives in Brixton in south London.

www.davidmicklem.com