You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

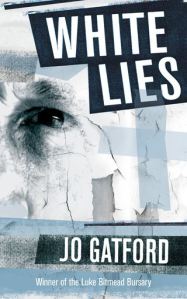

Go shopping Writer and Litro alumnus Jo Gatford’s debut novel White Lies was published in July by Legend Press. The non-linear story shifts perspectives between Matt and his dementia-stricken father, Peter, as they grapple with both their difficult relationship and the death of Matt’s half-brother, Alex. Her short story Dead Leg appears in Litro #104: History. Visit her website, Twitter and Facebook.

Writer and Litro alumnus Jo Gatford’s debut novel White Lies was published in July by Legend Press. The non-linear story shifts perspectives between Matt and his dementia-stricken father, Peter, as they grapple with both their difficult relationship and the death of Matt’s half-brother, Alex. Her short story Dead Leg appears in Litro #104: History. Visit her website, Twitter and Facebook.

What have you been up to since Litro #104?

Yikes, that was three years ago – I was busy creating a small human with my body back then. He’s now two and three-quarters and the circus of parenthood has become even more ridiculous. White Lies was longlisted by the Tibor Jones Pageturner Prize, won the 2013 Luke Bitmead Bursary, and was published by legend Press in July this year.

What are the last two books you read?

Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood, and Blackbirds by Chuck Wendig. Oryx and Crake was a research-read of sorts for a post-apocalyptic story I’m planning — and Atwood is the master of making the ordinary seem extraordinary, and the bizarre seem familiar. Blackbirds, on the other hand, is like being repeatedly kicked in the literary nuts while someone shouts made-up swear words at you. The book reads like the most electrifying, fast-paced screenplay you could ever hope to see, and I’m unspeakably excited to find out that it’s recently been commissioned as a TV series.

As a writer of both short stories and longer fiction, how did your process change when writing your first novel?

White Lies is actually my second novel — the first is still in a drawer feeling sorry for itself — so I’ve been flitting between short and long fiction for about a decade. At first, I wrote shorter pieces as a productive method of procrastination when I  was elbow-deep in novel editing and wanted a break. I joined a flash fiction group which runs a timed prompt session each week, which helped me to write regularly, learn to critique others, and develop my own work, all of which benefited my novel writing, for sure. It can take a lot of effort to put across a story with brevity.

was elbow-deep in novel editing and wanted a break. I joined a flash fiction group which runs a timed prompt session each week, which helped me to write regularly, learn to critique others, and develop my own work, all of which benefited my novel writing, for sure. It can take a lot of effort to put across a story with brevity.

What were your favourite parts about writing White Lies?

I loved writing Peter’s sections, agonising though they were at times. Writing an older character means there’s an entire lifetime to sift through, and it was voyeuristically intriguing to pick out his best and worst moments. Some of my favourite parts of the book are those that that wander into magical realism as Peter becomes more and more affected by his dementia.

There’s an almost uncomfortably intimate sensibility to the novel — how did this come about?

I definitely subscribe to David Foster Wallace’s assertion that “fiction’s job is to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” I enjoy being inside a character’s head, especially if they’re somewhat unpleasant or difficult to sympathise with. I try my best to draw out the kind of thoughts they would never say aloud. I suppose when you start delving into grief and depression and difficult memories, an uncomfortable intimacy naturally comes to the surface.

Is this the novel you always wanted to write?

I think it emerged as a development of some of the ideas in my first (shelved) novel, which was about the treatment of schizophrenia. The initial premise for White Lies was a man trying to work out how to grieve for a brother he hated, and the awkward contradiction of that situation. From there, Matt’s storyline was born. Peter’s experience of dementia was actually going to be a different book completely, but somewhere along the way the two narratives fitted together. It definitely wasn’t the novel I had expected to write, but it’s probably the novel I needed to write.

Was the story designed to be told from different narrative perspectives from the start?

I had always planned on switching between Peter and Matt, but initially there were a few other third person perspectives in there too. It soon became overcomplicated, however, especially with the non-linear timeline, and it seemed sensible to cut it back to just the two POVs. I do feel a little bit sad that the female characters don’t have more of a voice — they deserve a couple of books of their own — but I also think it was important that they are only seen through the eyes of the often grossly self-absorbed male characters.

What’s next?

The never-ending loop of submitting, editing, and hopefully publishing short stories. And of course trying to promote White Lies, which feels very odd because suddenly it’s a tangible thing. I’m also hoping to get some sort of funding this year to write my next book – or, you know, win some massive literary prize. That would be just fine.