You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

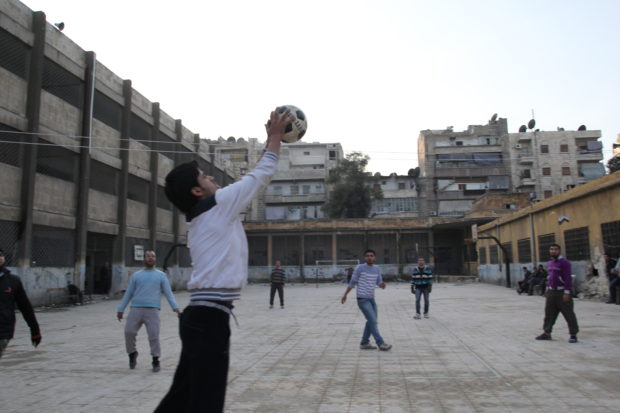

Photography by Reynaldo Leal

“God bless the Free Syrian Army!” a boy cries on an overcast, frigid February afternoon, his breath as gray as his surroundings, “God bless the Free Syrian Army!”

Through the shattered window of an Aleppo school, the boy watches rebel fighters, stocking caps pulled low around their ears, none older than twenty-five, all of them once university students, all of them with beards, some full and thick, others patchy and spare, play soccer on a basketball court, their Kalashnikov rifles propped against a mortared wall near ruined plastic chairs where their commander, Alhusen, and other rebels sit and watch.

The players: Ahmad, Abualeez, Yasser, Rashid, Akran and Abdullah.

Ahmad juggles the ball on his knees, shows off. He considers anyone wearing a Syrian army uniform a target. Man, woman, it doesn’t matter. One time, he shot a man who had found a green Syrian army helmet and placed it on his head. He should never have worn it. Stupid man. Occasionally, a soldier – a target, Ahmad calls them – crosses the street alone and Ahmad sees him clearly and takes the shot but at other times when a target uses human shields Ahamd can’t shoot. He gets angry, calls the target a coward and many other worse things because coward is too good for such a chickenshit. As long as he thinks of them as targets they are less than human.

He passes the ball to Abualeez, who dribbles up the court. Abualeez was born in Aleppo and studied engineering at Aleppo University. When the FSA entered the city, he saw it needed fighters and joined. At the time, he didn’t know how to carry a gun. The FSA sent him to a training camp for fifteen days where he learned how to storm buildings (“you run up stairs screaming and shooting”), how to shoot (“point and fire”) and how to clean his weapon (“shoot it to keep the barrel spotless”). He enjoyed training, holding his gun and the expertise he began to feel as he learned how to use it, and he liked how it changed him. He felt more confident. Children followed him and chanted his name. Adults stood aside for him. His self-assurance abandoned him in his first battle. It was a new experience and he ran from the shooting, the noise, but killing is not new anymore and it is the silence between battles that disturbs him. Waiting, knowing something will happen to shatter the quiet but not knowing what or when. One time, three rockets hit three buildings around him. Other soldiers dropped to the ground for cover but he kept walking. He doesn’t know why. Months and months of war, man. That’s a long time. You get used to it. He remembers one battle above all others, an attack on an army school south of Aleppo. At first the FSA failed to secure it. There was too much shelling by the government. Too many FSA soldiers killed. The rebels retreated and organized a fresh attack. Abualeez felt nothing but a desire to liberate the school and kill government forces. During the second assault, he fired his weapon and Syrian soldiers fell before him like trees and still he felt nothing. Then his brother was shot in the left leg and right foot and Abualeez became crazy with anger and fear. His brother lived and Abualeez, submerged in a sense of overwhelming relief, praised God and then at some point as he surfaced from this good feeling, he doesn’t know when, he resumed feeling nothing.

He rushes toward the goal, elbowing Yasser, but Yasser snatches the ball. Yasser passed a hospital his first day in Aleppo after the revolution started and saw a dead woman, a baby spilled out of her body still attached to its umbilical cord. Yasser could not sleep for days. This woman could have been his wife. Then he put those thoughts out of his mind. It was a revolution. She had left this world for paradise.

Yasser stumbles and his legs intertwine with those of Abualeez and Abualeez takes control of the ball and passes to Rashid, who holds it beneath his right foot and surveys the court. He was an architect student when the revolution started and served as a medic for the FSA. He threw Molotov cocktails but admits they did little damage. Then he started shooting videos because the FSA had no public relations. He posted the videos on YouTube. One night, he viewed a video he removed from a dead government soldier. Four naked men knelt at a wall, hands tied behind their backs. Syrian soldiers in gray uniforms stood behind them shouting, “Don’t move!” The naked men huddled close together, backs grime-smeared. Then the soldiers drew knives and lunged forward, stabbing the men in their heads. The men fell to their sides, blood gushing.

“Don’t move!” the soldiers said, and thrust again.

The wounded men struggled to a sitting position.

“Don’t move!”

Holding a bloody knife, a soldier stabs each man yet again.

“Don’t move!”

Rashid takes a shot at the goal but Akran stops the ball with his chest, skirts around Rashid and dribbles in the opposite direction. Akran’s father used to beat his mother. Months ago she left the family for Turkey and in her absence, his father turned his anger on Akran and threw him out of the house. He lived on the streets of Aleppo until an FSA leader saw him scavenging in trash. “What are you doing?” he asked. He took Akran in and treated him like a son, enlisting him in the FSA. Akran learned how to shoot a Kalashnikov. His hands shook the first time he went into battle. FSA soldiers shouted insults at the Syrian army. “You have big noses. Bigger than anything else on your body.” Akran laughed and joined in the taunting. When he shot at the enemy his hands stopped shaking. That is the thing about war, he has learned. Keep busy, keep shooting, keep moving and you won’t be nervous. He has a brother in the Syrian army. He doesn’t know if his brother supports the regime or if he was conscripted. If he supports Assad, Akran will kill him no question, no regrets, no shaking.

He kicks the ball out of bounds. Alhusen, slouched in a chair sipping tea, too bored to play, picks up the ball. He commands two units of fifty soldiers, one nearby, the other in Old City. He fought in the jihad against the Americans in Iraq and the Israelis in Lebanon and then returned to Syria to fight in the revolution. He assumes he’ll fight somewhere else after this if there is a somewhere else after this. In August 2011, the Syrian army stormed a rebel-held neighborhood in Idlib. Alhusen lost three of his best men in a seven-hour battle. Two of them were brothers. Their family was so sad that now he doesn’t allow brothers to enlist in the same unit. The brothers believed in God and the revolution. They knew they could die. He took their bodies to the family and kissed the head of their mother. He will never forget her face, no tears but grief mapped in every line. When she saw her sons, she said, “Thank God they are martyrs.” Alhusen was proud of her. She knew her sons were in a good place. The father wept. Sometimes, men can’t control themselves when disaster happens, especially when they lose a son. Dead government soldiers, he knows, have families too, but when they kill women and children he has no choice but to kill them. War is so bad and dirty, especially against your own people. Alhusen has seen so much death he misses it when there is a lull in the fighting. Like not having your shadow, something is absent. He wonders if they will all need psychotherapy when the war ends.

Getting up slowly like an old man wary of losing his balance, he tosses the ball to the players, and amid a general scuffle, Akran gets it, dribbles down court and shoots, but Abdullah, the goalie, blocks it. Abdullah really loves guns. Every week he must shoot a target. If not a government soldier, then a window, the side of a building, anything. He grew up on a big farm. Every year he and his family had to protect it from neighbors who would try to steal their crops during the twenty days of harvest. In1999, he bought a shotgun, in 2002, a Kalashnikov. He fought in the countryside of Idlib when the revolution started. The government soldiers shot every which way. The shelling was so loud Abdullah’s head filled with the noise of explosions, a great swelling roar. At that time, the FSA had only rifles and homemade bombs. One day, they put bombs along the street of a village as military vehicles turned onto it. The front and rear vehicle struck the bombs and exploded. Abdullah thought the engagement would last half an hour. Instead, it persisted all day. The FSA killed most of the soldiers. The soldiers cried and shouted, they were so scared. They offered to surrender but their officer would not allow it, a stupid decision, and Abdullah shot them.

He kicks the ball down court.

“How much longer do we have?” he shouts.

“The game or life?” Alhusen asks.

They all laugh, keep playing, until they no longer can. Exhausted, they sit with Alhusen and breathe loudly, sucking in air as their hearts slow and their breathing relaxes into the uneasy, listless stillness around them, the acrid air, the empty school, the vacancy of this pause in the fighting, and then they hear an explosion far off but close enough and a jolt of adrenaline replaces the tension and brings them to their feet with an eagerness bordering on joy. “Allahu Akbar,” they shout, “Allahu Akbar!” and the boy watching them joins in the celebration. Abualeez can’t restrain himself. As the others move in the direction of the explosion, he sprints onto the deserted court, kicks the ball toward the goal and throws up his arms in victory. Hurrying back, he grabs his weapon and slaps Abdullah on the back.

“Score, man,” he says.

Photography by Reynaldo Leal

About J. Malcolm Garcia

J. Malcolm Garcia is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.

- More Posts(5)