You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

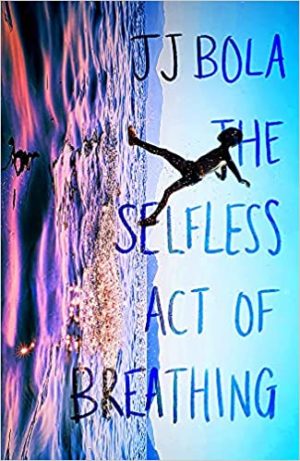

A boy running on water: This is the image we are offered on the cover of JJ Bola’s new novel, The Selfless Act of Breathing. The photo itself is taken by Turkish photographer Aslı Ulaş Gönen (Instagram @gonenasli), depicting a young boy being thrown playfully into the water by his father. Pasted across the book, with the father removed (not insignificantly), the boy is ambiguous: Is he trying to stay afloat? Run away? Jump in? This ambiguity is transferred onto Michael Kabongo, our protagonist, as he struggles to stay afloat, resolves to run away, wants to jump in. For Michael, life is a wave washing over us and the water is often cold, dark, and miserable.

The book’s first page lands us straight in London Heathrow as Michael is rushing to catch his flight to America. The tension is built up effectively, as the time is announced throughout the passage while Michael is running towards his gate, and our stress collapses as Michael does onto his seat. But his journey is no conventional holiday; Michael is leaving for America with the intention of killing himself once all his life savings have been spent, and each chapter in America ends with the amount in Michael’s bank account. Money, quite literally, is life. The rest of the novel flits between his past in London, told from Michael’s point of view, as a teacher and son, and unravels his explorations in America, in a detached third-person perspective.

The intimacy of the first-person narrative is helpful in the London passages to understand the sudden move to America, the resolve to die. Turbulence defines Michael’s mind, and parts of his upbringing: moving to England, growing up without his father, violence, and the lack of stability within his working-class roots. The switch into third-person narrative for Michael’s American odyssey works effectively to capture his disillusion and detachment at this point in his life. What we lose in insight to Michael’s mind is compensated for by the use of italics as Michael’s thoughts. Sometimes the large chunks of italics expressing Michael’s point of view risk undermining the third-person narrative, as if seeking to return to the first person, but their appearance is infrequent enough to avoid considerable awkwardness. This alternating narrative perspective in addition to the disordered timeline, with varying locations and hours, works well to mimic Michael’s turbulent mindset and memories. We crave the stability of chronology and understanding, but Bola triumphantly resists.

This is JJ Bola’s second novel, written at the same time as his nonfiction book, Mask Off: Masculinity Redefined. The parallels are undeniable; the construct of masculinity is presented as oppressive throughout the novel, particularly for the Black boys and men at Peckriver Estate and Grace Heart Academy School, where Michael lives and works. Bola wrestles with this wonderfully, introducing masculinity’s self-destructive poison into the novel’s main dilemmas, whilst at the same time acknowledging the destruction and violence masculinity inflicts upon others. Towards the end of the novel, Belle, a sex worker living in Harlem, reveals the threat masculinity poses towards women and marginalised genders, alongside men themselves.

Bola’s focus on masculinity leads him to make fathers, their presence and absence, the focal point of the novel. Michael’s absent father, whose death remains shrouded in mystery, haunts our protagonist, dictating interactions with other father-figures in the book: He resists the pastor as his father, and longs for his friend Jalil’s Baba (father) as his own. Michael becomes something of a father himself, to the troubled Duwayne in his class. Duwayne’s bursts of anger trigger similar outbursts in Michael, while his signs of growth and happiness instil in Michael a paternal glow.

Other than father-son relationships, romantic subplots pepper Michael’s past and present, with his ambiguous work-wife Sandra and intensely loved-up Christelle in the former, and the intelligent, guarded Belle in the latter. There is a little frustration with these subplots, since these women are introduced only to be taken away, or rather us to be taken from them. But on finishing the book, I determined this was effective in reflecting Michael’s detachment to the people and world around him, even in the face of love.

On the surface, given Michael’s detachment and resolve to die, the novel might appear to be obsessed with death. In fact, the book’s first part is prefaced by a reminder of our mortality: memento mori (remember that you [have to] die). However, it soon becomes clear that it is not death the novel seeks to hold, but rather life, or, more specifically, living. When men attempt to mug Michael and his new friend Sara in Los Angeles, Michael asks the men to kill him. His italicised thoughts reveal that he is not “a man who wants to die” but “a man who wants to live, and dying is the only way” he knows how. As the book accelerates to its close, the final line reminds us that it is love, life’s greatest strength, that “ephemeral or eternal” flame, which carries us forward, and breath, not death, has the final word.

This is not the only example of Bola’s captivating language within this book. Reports of Bola’s lyricism drew me to this novel in the first place, and I was not disappointed. His mind works in interesting ways to produce thought-provoking comments on setting and people, and everything is said in stunning language which never grows tired. Comparing London lampposts to wilting flowers, a plane landing to a leaf falling to the ground, and silence to a genocide, I was constantly captivated by the workings of his mind. His language works to beautify places often presented as void of beauty or unworthy of artistic representation, such as council estates and the backstreets of London. His depictions of love, too, which drive the novel, are intense and moving; love has been said many times and in many ways, yet Bola makes it new.

The dialogue within the book sits beside the poetic descriptive passages to keep the narrative alive, and Bola is not afraid to replicate actual spoken word, in many different registers and even languages, with Michael’s mother speaking to him in Lingala and French. Conversations between Michael and his close friend Jalil on topics of decolonisation and Eurocentric beauty standards sit alongside interjections of “bro” and “innit”, to reinforce the notion that such conversations should not be – and are not – confined to the closed circles of academia, or Standard English.

The ending is difficult, and not entirely comprehensible both in terms of plot and execution. It felt somewhat rushed: Belle and Michael’s relationship went through a rollercoaster of highs and lows in the space of only a few chapters, and I would have liked more time to believe in each curve. Michael’s final decision was hard to follow due to the lack of explanation; up until the final chapter, I was convinced the ending would be a different one, although this is perhaps not a fault. However, Bola manages to rectify any holes in the plot with the beauty of the ending’s language, and the final chapter’s breath-taking prose, which begs to be poetry, rendered me unable to judge the book anything other than a success.

As we struggle through the injuries of gender performance and binaries (particularly for those who exist outside them), rising male suicide rates, and systemic racism, a book exploring the destructive force of masculinity and racism and the restoring force of love seems vital. Couple that with spellbinding prose and an “unputdownable” plot, and JJ Bola has succeeded in writing a novel that’s not only a pleasure to read but is a necessary navigation through our society. Change bubbles under the cover boy’s feet, and we can only hope it washes us all.

The Selfless Act of Breathing

By JJ Bola

Simon & Schuster, 272 pages

About Zadie Loft

Zadie read Classics at Downing College, Cambridge, and is currently studying for an MSt in Creative Writing at Kellogg College, Oxford. She has previously been a columnist for the Cambridge Varsity newspaper and a prose and verse contributor for La Piccioletta Barca. She is Litro's Editorial Strategist.