You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Adèle appears to have it all. A successful journalist specialising in North African affairs, she lives in an elegant Parisian apartment with her surgeon husband and their young son. But beneath the surface of her bourgeois respectability, Adèle has a secret – she is consumed by an insatiable need for sex. She wants to be ‘devoured, sucked, swallowed whole’ by anyone, it seems, who isn’t her husband.

Adèle appears to have it all. A successful journalist specialising in North African affairs, she lives in an elegant Parisian apartment with her surgeon husband and their young son. But beneath the surface of her bourgeois respectability, Adèle has a secret – she is consumed by an insatiable need for sex. She wants to be ‘devoured, sucked, swallowed whole’ by anyone, it seems, who isn’t her husband.

Adèle is Slimani’s first novel; it was published in France in 2014 and has just been translated into English by Sam Taylor on the back of the success of her second novel, Lullaby, which won the Prix Goncourt in 2016 and captivated readers in the UK when it was published here last year. Both are dark, disturbing novels, and not just for the brutal subject matter of child murder and sex addiction but because Slimani explores nightmarish extremes of female subjectivity. She sets maternal duty against desire, ambition and liberty, exposing loneliness at the heart of family life.

I found Adèle as arresting as Lullaby, but not quite as satisfying. I did not like Adèle, but that shouldn’t have mattered. What I found most difficult was that I couldn’t understand her. From the outset, she craves violence and degradation. In the shower, she wants ‘someone to grab her and smash her skull into the glass door.’ On the metro, she sees a man and thinks: ‘He’s ugly. He might do.’ When she stops off to visit a lover, the act is neither ‘obscene enough or tender enough’ to gratify her. She fantasises about her boss, carefully choosing her outfits and crafting intelligent stories to impress him, only to realise he is ‘potbellied and clumsy’ in the flesh.

Rather than erotic and daring, Adèle’s sexual encounters are relentlessly devoid of pleasure. Her ‘favourite moment’ is before the first kiss when she is ‘the mistress of the magic’. It is the situation not the act that arouses her, and yet she is driven by a deep compulsion to give men pleasure. Her only agency is in choosing who to seduce, but she isn’t very choosey.

Adèle does not fit the mould of a modern #MeToo woman. She is submissive and likes being overpowered. When she begs two drug-dealing prostitutes to hurt her, she is left ‘just a shard of broken glass now, a maze of ridges and fissures’. The choices she gives herself are a bit frustrating – to fuck herself into oblivion or accept the living death of family life.

Adèle shares a lot in common with Madame Bovary. She’s shallow and materialistic, restless in her marriage to a well-to-do doctor, and unfulfilled by her role as a mother. But while Emma struck me as flawed and noble, sacrificing herself for a dream of romantic love, Adèle doesn’t seem to care very much about anything. She clings to the respectability her husband affords her but sees ‘family life as a dreadful punishment’. Her love for her son is ‘a rough, misshapen love, dented and bruised by everyday life’. She loses interest in her work and begins to plagiarise articles and invent sources once she has seduced her boss, for ‘What was the point of working now that she’d had him?’

Slimani doesn’t offer any justification for Adèle’s behaviour. We understand that she felt stifled growing up in a provincial town, that a trip through the seedy Pigalle area of Paris when she was a girl, with her mother and a man who wasn’t her father, first inspired her feelings of ‘fear and longing, disgust and arousal’. She was later stirred by a passage in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and she lost her virginity on the damp floor of a garage to a heartless boyfriend. But none of these really explain Adèle’s compulsions.

When Adèle’s husband Richard finds out about her many affairs, he takes her to live in the Normandy countryside. For a woman who feared losing everything, most of all her freedom, rural life is a prison. Adèle has no phone, no money, no car, and no means of escape – until her father dies and she is released to attend his funeral. What happens next is heartbreaking. Adèle betrays herself and our hopes for her. She is an enigma. Richard can’t solve her, and neither can we. She resists interpretation and redemption.

Adèle is a brilliant snapshot of sex addiction. It’s compelling and propulsive, and delivered in elegant, bracingly spare prose, but I can’t say I found it an easy read. I never quite got to grips with the emptiness fuelling Adèle’s addiction, and by the end, although I pitied Adèle, I also felt a bit numb. Torn between extremes of maternal obligation and desire, both of which will destroy her, Adèle has no real liberty. And Slimani – in presenting female sexuality and family life as binaries – doesn’t offer any answers. It’s a deeply troubling novel, one that will stay with me for a long time.

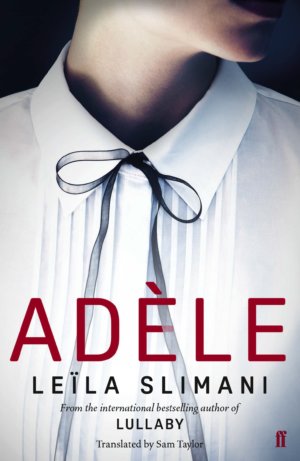

Adèle is out now from Faber & Faber

About Jennifer Kerslake

Jennifer Kerslake is an editor and writer. Born in Devon, she now lives in London where she works for the Orion Publishing Group.