You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

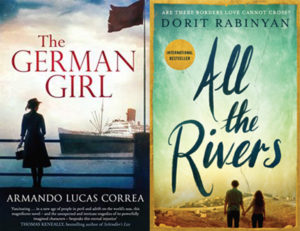

Go shopping All the Rivers, the new book by best-selling Israeli novelist Dorit Rabinyan, and The German Girl, the debut from award-winning Spanish journalist Armando Lucas Correa, both share a deep concern with that most contentious and maligned figure of current times: the refugee. It’s significant that both authors choose to set their complex narratives in the past and the present, reinforcing the truth that those caught in diasporas over the centuries have faced the same challenges as those fleeing a homeland now. Rather than focus on people triumphantly maintaining their sense of identity as they find themselves displaced by history, both Rabinyan and Correa explore the uncertain lives of people caught in transit; in temporal situations, longing for the past, but always believing the future holds something better. And while both novels employ, respectively, many of the conventions of romantic and historical fiction, their urgent concern with universal dilemmas allows them to transcend their genres.

All the Rivers, the new book by best-selling Israeli novelist Dorit Rabinyan, and The German Girl, the debut from award-winning Spanish journalist Armando Lucas Correa, both share a deep concern with that most contentious and maligned figure of current times: the refugee. It’s significant that both authors choose to set their complex narratives in the past and the present, reinforcing the truth that those caught in diasporas over the centuries have faced the same challenges as those fleeing a homeland now. Rather than focus on people triumphantly maintaining their sense of identity as they find themselves displaced by history, both Rabinyan and Correa explore the uncertain lives of people caught in transit; in temporal situations, longing for the past, but always believing the future holds something better. And while both novels employ, respectively, many of the conventions of romantic and historical fiction, their urgent concern with universal dilemmas allows them to transcend their genres.

The refugees of Rabinyan’s controversial novel are the parents of its heroine, Liat, an Israeli who is herself displaced to New York in 2002 to study translation from Hebrew into English. The lives of Liat’s mother and father, Persian Jews who left Iran for Israel in the mid-sixties, inform her sense of temporality and contingency. As Mizrahi Jews of Middle Eastern origin, they are perceived as both Arab and Jewish, which contributes to Liat’s sense of indeterminacy. When she falls for Hilmi, an intense Palestinian artist, the fear that love’s paradise will disappear is magnified by the insecurity of her background. After every perfect Sunday walking hand-in-hand with Hilmi around the cafes, bars and galleries of Brooklyn, she reflects on all the ‘men and women whose paths had crossed and who had spent the weekend together, taking comfort in each other, salving their loneliness in this vast city . . . Just as quickly as it started yesterday, it could be over tomorrow’. Their tenuous love affair is ‘immediate and temporary, just like life’. This ever-present paranoia pervades the book, along with Liat’s sure knowledge that when she returns to Tel Aviv, she will have to relinquish Hilmi, as their ‘shameful’ relationship would never be accepted by her family or the wider community.

For most of the novel, the cultural and ideological schisms seem too deep for the lovers to negotiate. Indeed, the couple have their first argument after their first date, when Liat reminisces about her military service, pledging her ‘“allegiance to the State of Israel . . . Uzi butt squeezed in my left hand”’. Hilmi observes: ‘“Just like in Hamas . . . With the Kalashnikov and the Koran.”’ Liat’s response is anger at the perceived equivalence: “‘It’s not at all the same thing . . . The scene might look similar . . . but to compare the IDF with Hamas?!”’ As their love affair progresses, Liat starts to avoid her Israeli relatives in New York; though there is a tense scene when Hilmi is recognised as an Arab by a group of boisterous Israeli teenagers on a subway station. Liat immediately fears they will mistake her identity too because of the scarf over her ears: ‘I can guess what they see: nothing but eyes, veiled by this mock hijab; they probably think I look like some kind of terrorist’. The scene is intensified by being set a year after 9/11; with UN advisers in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan well underway. The demonisation of Arabs, always active pre-War on Terror, is now in full effect. Later, at a Shabbat dinner, the talk is all of Bush’s proposed invasion, and Hamas terrorist attacks. Liat muses darkly on what her father would say if he could see her now, with ‘not just any Arab, but [one] from the Territories’. Inevitably, they are doomed to separate, though Liat’s sympathy for Hilmi grows when he reveals that his parents were refugees too, displaced from a village near Jericho in 1948, ending up in a transit camp before moving to Hebron. By the age of fifteen, he had spent four months in jail for spraying the Palestinian flag on a wall. This information gives her a crucial insight. She can finally see ‘Israel as it appears to its enemies’. But consanguinity is bound to prevail – both Liat and Hilmi are fiercely partisan about their own people. The book’s centrepiece is an excruciating dinner with Hilmi’s extended family, in which his brother Wasim prosecutes an insidious argument for the bi-national solution versus the Two State solution, based on the hope that the Arabs’ superior birthrate would allow Palestinians to claim sovereignty in the end. Liat responds explosively, ‘as though nothing less than the future of Israel’ rested on her shoulders.

In the end, when Liat returns to ‘lofty, laid-back, languid Tel Aviv’, and Hilmi goes back to the Ramallah, neither feels at home. The ‘menacing grey concrete wall’ is under construction, and there is ‘no straight line running between those two dots of ours, only a long and torturous road, dangerous for me, impassable for him’. Praised by Amos Oz, Rabinyan’s compelling novel questions whether love and family life can survive such a dangerous journey, though maybe not as searchingly or viscerally as in recent fiction by the Mizrahi writer Ayelet Tsabari, in her short story collection, The Best Place on Earth, or Claire Hajaj’s Ishmael’s Oranges, also about a love affair between an Arab and Jew.

Armando Lucas Correa’s The German Girl, also comes garlanded with praise from an established novelist, in this case Thomas Keneally. As with Schindler’s List, Correa’s powerful and timely book is based on a true story from Word War II, the voyage of the St Louis, a transatlantic liner that sailed from Hamburg to Cuba in 1939 with 937 Jewish passengers on board, only to be turned away by the Cuban authorities, allowing only those able to afford an extortionate bond to set foot in Havana. The novel’s early chapters set in Berlin vividly evoke the terror of persecution through the eyes of twelve-year-old Hannah Rosenthal. Accused of being ‘dirty’ by anti-Semitic Berliners in the street, she climbs into a bath with all her clothes on to get rid of ‘every last trace of impurity’. Ironically, her looks are mistaken for Aryan by a photographer, who takes a picture that puts her on the cover of Das Deutshce Mädel (The German Girl), a photojournal celebrating Nazi notions of racial purity. In a parallel narrative that isn’t always successfully integrated with Hannah’s story, Anna Rosen, a twelve-year-old girl in present-day new York receives a mysterious package that contains an issue of the very magazine bearing Hannah’s picture, starting a quest that leads her and her mother to Cuba, and so to the grave of her father who died in the 9/11 attacks. It’s later revealed that Hannah was one of the passengers of the St Louis who made it to Cuba, and she brought up Anna’s father after the war. While these two narratives reinforce the hopeful notion that a refugee might flourish in any country given the support of the host nation, they sometimes feel tenuously juxtaposed, with the reader wanting to get back to Hannah’s tense journey on the St Louis.

The novel is at its most powerful when making the reader think about the plight of families trapped in transit, and what it might mean to die in the attempt to escape an oppressive regime, or be returned to the place of danger because of mere bureaucracy, or an inimical country who initially promises safe haven. All these issues are as relevant today as they were in 1939, with the plight of Syrian refugees. Correa is excellent on the tiny details that bring to life an individual refugee story, with Hannah escaping from Berlin with just ‘a muddy stone. A shard of smoked glass. A dry leaf’. And while her mother manages to get her jewels out of Berlin, despite the ‘cruel informers’ or ‘Ogres’, others are not so lucky. The lack of parity is shown when only 28 of the St Louis’ passengers are allowed to disembark, with the rest sent back to Europe, including Hannah’s father, who later perishes, along with many of the ill-fated refugees, in Auschwitz.

Impeccably researched and nimbly written, The German Girl also resonates with current times when transcribing Hitler’s radio speeches. Unsurprisingly, they contain a queasy echo of today’s hate-speech and the rise of the ‘alt’ right; with the Fuhrer referring to German Jews (some of whom, including Hannah’s grandfather, were decorated with an Iron Cross in the previous war) as ‘worms, delinquents, undesirables, aliens . . . poisoning our politics’. While both The German Girl and All the Rivers signally warn against intolerance and the dangers of repeating history’s mistakes, both illustrate how refugees’ journeys are often longer than we might imagine, and how hard it is to find a real and lasting home.

About Jude Cook

Jude Cook lives in London and studied English literature at UCL. His first novel, BYRON EASY, was published by William Heinemann of Random House in February of 2013. He has written for the Guardian, the Spectator, Literary Review and the TLS. His essays and short fiction have appeared in Litro, Structo, Long Story Short and Staple magazine.