You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Arthur Schnitzler wrote his now-notorious play La Ronde in 1897 for the amusement of a small circle of friends. The title is a nod to the play’s cyclical nature, its ten characters introduced a pair at a time, with a single character remaining from one scene to the next and each scene culminating in a sexual act. This systematic structure, ending in a complete circle, couples soldiers with whores, gentlemen and maids, actresses and counts. La Ronde was not performed for another twenty years after it was written, and then met with violent criticism and a six-day obscenity trial. Its sexually explicit content offended, but its social transgression – pairing aristocracy with the demimonde in its unflinchingly honest look at the ubiquity of sex – was also contextually explosive.

Sex, for Schnitzler, is the great leveller. Its urges consume all, and its repercussions (suggested by Schnitzler in the spread of syphilis) are blind to affluence and class. It was a powerful message, rarely explored in the discourse of fin-de-siècle Vienna – although not missing from peoples’ minds (the psychosexual writing of Sigmund Freud, fellow Viennese and a great admirer of Schnitzler’s work, is testament to the interest the intelligentsia were taking in this subject). Few were bold enough to commit these ideas to paper so explicitly, however, and Schnitzler found himself the victim of an anti-Semitic backlash in Germany as a result of his writing.

At what point, then, did this famously controversial play shed its energy? Richard Listor’s adaptation at the White Bear Theatre – Swings and Roundabouts – is symptomatic of the swathes of bloodless counterfeits that La Ronde has inspired. This production, although loyal to the sexual merry-go-round of Schnitzler’s original, has been relocated to a place of unspecific modernity, the maid reimagined as an intern, the count a movie producer. The spin of sexual encounters remains, but the social impact of these acts is lost: without the carefully marked class divisions of Schnitzler’s original context, these liaisons are not particularly polemicizing. The message they appear to be conveying – that people will sleep freely with more than one sexual partner – is not new to London audiences.

The climactic moments here are notably lacking in passion. Charles Spencer famously called David Hare’s adaptation of the play “theatrical Viagra”, yet this production is curiously sexless, brimming with stilted conversations and too-prompt blackouts. It is remarkable to find – one hundred and seventeen years after its creation – that La Ronde’s content is still skirted around in performance. A strange self-censorship seems to be in practice, which jars with the play’s enduring popularity. Its turbulent history and the compelling power of its roundel-like structure recommend it for adaptation, but its erotic core remains problematic.

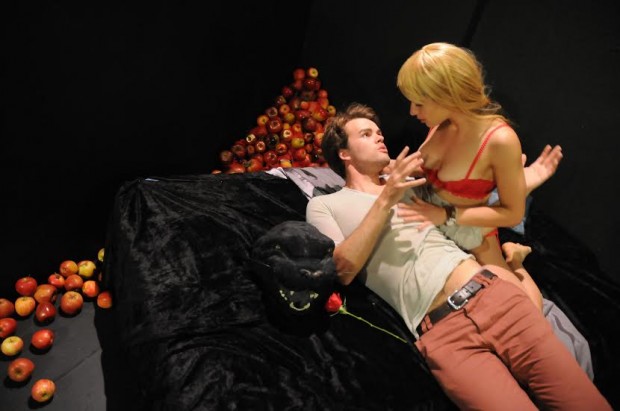

Free from the social implications of Schnitzler’s original, and lacking the lustful energy so integral to this play, Swings and Roundabouts is left a pleasant but subdued reworking. A dissonant variation on Grieg’s Peer Gynt plays as we enter (a clever touch, given Schnitzler’s admiration of Ibsen), welcoming its audience into an auditorium bare but for the scores of apples heaped high around an unmade bed. The allusion to Eden is clear, and the arrival of a gum-chewing prostitute cartwheeling across the stage stresses this central theme of temptation.

It is the motivation behind the liaisons which is of interest here. In this succession of scenes we see snap-shot moments of honesty: relationships formed out of boredom, ambition and inebriation. And the swift carousel of sexual encounters is convincing, despite the sometimes stilted nature of the script. The cast carry these conversations well, finding comedy in moments of awkwardness and pathos in scenes of betrayal. A particularly impressive performance was delivered by Matthew Crowley, who came to acting through dramatic workshops at Pentonville prison where he has been serving a twelve year sentence for robbery. Elsewhere, Anna Danezi is at turns amusingly apathetic and adoring, and Anna Brooks-Beckman conveys persuasively the emotional turmoil of adultery.

This production looks keenly at the diverse aspects of sexual relationships today, but it has lost the shock of Schnitzler’s original. The transposition of Schnitzler’s play to the modern era should not, I think, lose it its exhilaration, nor its relevance. He has been adapted badly before, but he has also been adapted well: David Hare updates La Ronde absorbingly in The Blue Room, while Joe DiPietro’s Fucking Men reimagines it in a homosexual context with interesting effect. On screen, Kubrick immortalized Schnitzler’s Dream Story in Eyes Wide Shut, demonstrating the enduring social and sexual pertinence of the Austrian author’s stories. Swings and Roundabouts felt stiff, in contrast, a pallid incarnation of the pioneering text from which it was adapted.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.