You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

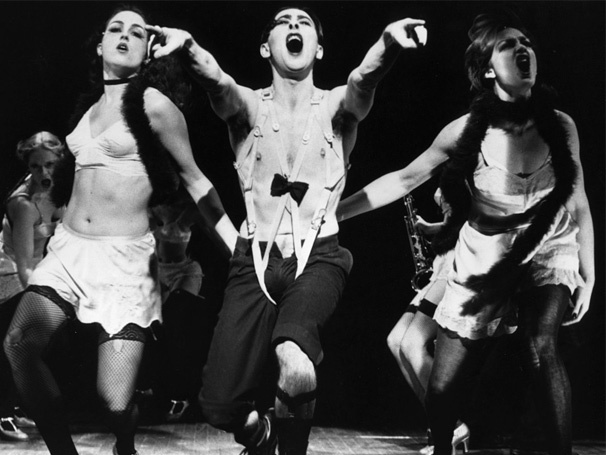

Life is anything but a cabaret in the bleak days of late Weimar Berlin. The girls may be beautiful; the Emcees may be here to serve; troubles may be ostensibly checked at the door – but in Sam Mendes’ revival of his 1998 interpretation of the 1966 Kander and Ebb classic, the illusory nature of the pleasures of the Kit Kat Club has never been more clear. The Kit Kat girls are – though lovely – gaunt and sunken-cheeked; as the Nazis rise to power over the course of the musical, they don black wigs to become eerily more similar, spectral reminders of the chilling homogeneity to come.

Headlining the whole affair is Alan Cumming as the Emcee (reprising his 1998 performance) – a role so pitch-perfect for Cumming that it almost, counterintuitively, feels like it’s being played safe. Cumming is a consummate performer (though he’s chewing the scenery rather less vociferously than in his excellent 2013 one-man Macbeth, perhaps my favourite Broadway show of last year): equal parts showman and diva, but – surprisingly for Cumming – his eagerness to shock and awe (not to mention seduce) his audience into submission feels tame, if somewhat vulgar. Cumming knows what works (and work it nearly always does), but – with the exception of the haunting “I Don’t Care Much” – his performance can feel by-the-numbers. The Emcee’s response to the Nazis, furthermore, tends less towards black humor than frivolity: the odd Hitler impersonation falls flat, and the final image of Act I – a swastika carved into the Emcee’s bare buttocks – feels less transgressive than cowardly, as if Mendes and company have little faith in the swastika’s power to shock on its own.

That said, however, the production overall is fantastic: grounded in part in the revelatory performance of Michelle Williams as Sally Bowles. Portrayed as an overgrown child tap-dancing in her mother’s clothes (a motif made clear early on with an innovative interpretation of “Don’t Tell Mama”, in which Williams kicks her heels from an oversized chair), Williams’ Bowles is hyperactive, fidgety, and heartbreakingly insecure: less Liza Minelli than Holly Golightly. It’s difficult to overshadow Cumming, but Williams manages it: her final, achingly simplistic delivery of “Cabaret” is far more compelling than the razzle-dazzle that’s come before; her final breakdown is among the best performances I’ve seen on any stage on either side of the Atlantic.

Such a childlike interpretation of Bowles, along with emphasis on her lover Cliff’s bisexuality, makes for an odd central romantic pairing. The first act seems to set Sally’s affections for Cliff as so completely unrequited (“Are you a homosexual?” she asks him, at one point; he does not reply) that the revelation that he might be the father of her child seems almost ludicrous in context. Their relationship as it plays out – Sally and Cliff more as co-dependent friends more than lovers – is compelling, but this production could have fleshed out how, exactly, such friendship ends up in coitus.

Yet the lessened emphasis on the Cliff/Sally romance allows other pairings to shine: most notably that of the decidedly unglamorous, but utterly compelling relationship between tolerant landlady Frau Schneider and Jewish shopkeeper Herr Schultz (Linda Emond and Danny Burstein), whose relationship comes across as a rare moment of human connection in a world falling apart. So too the chilling figure of Fräulein Kost Kost (sung with gorgeous discordancy by Gayle Rankin): a prostitute for whom Nazism represents order in a life of chaos. While Sally’s presence is overwhelming – by the sheer force of Williams’ charisma – Williams is a generous performer, and ultimately we feel that Cabaret’s tragedy is not merely the decline of Sally Bowles, but that of her whole world.

Gorgeously designed, slickly lit, and, despite a few missteps, stunningly directed – the final reprise of “Wilkommen”, in which Cumming gleefully announces a now-empty orchestra, is perhaps the play’s most devastating moment – this cynical Cabaret may not offer the warmest wilkommen, but it will stay with you long after you leave.

Cabaret continues at Studio 54 until July 11th. See here for more information.

About Tara Isabella Burton

Tara Isabella Burton's work has appeared or is forthcoming in Arc, The Dr TJ Eckleburg Review, Guernica, and more. In 2012 she received the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize for travel writing. She is represented by the Philip G. Spitzer Literary Agency of New York; her first novel is currently on submission.