You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Whether it is possible to “go modern” and still ‘be British’ is a question vexing quite a few people today… The battle lines have been drawn up: internationalism versus an indigenous culture; renovation versus conservation; the industrial versus the pastoral.

The tension that he here indicates points to crucial facet of his own œuvre, much of which was concerned with the negotiation between a British identity rooted in the past and one capable of embracing a modernity associated with internationalism and change.

This retrospective begins, predictably enough, with Nash’s early work rendered in a romantic idiom, largely under the influence of Blake. These diffidently dreamy pieces suggest nothing of his later modernist leanings despite the tentative associations early in his career with the more experimental side of artistic practice in Britain: he joined Roger Fry’s Omega workshop and exhibited with Bloomsbury artists at the Friday Club. His work was also shown at The Camden Town Group Show and Others in Brighton in 1913 and (the now iconic) Twentieth-Century Art: A Review of the Modern Movements at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1914.

It was as a result of the experience of war that his style was to change. Significantly. In a letter to his wife from the front, Nash remarked: ‘I begin to believe in the Vorticist doctrine of destruction almost’, and it was to its disruptive idiom that he turned in his depiction of battle scenes while working as an official war artist. A style that had bombastically celebrated the aesthetic of the machine now lamented the destruction caused by a mechanised war. In works such as Void (1918) and The Menin Road (1919), jagged, geometric forms are used to depict a broken landscape

While the end of the war saw his return to landscape painting, his work still tended towards modernist innovation. His seascapes, in particular, involved a flirtation with abstract form – both The Shore (1923) and Winter Sea (1925-37) feature simple geometric forms that are devoid, at times, of clear reference. But it was from the early 1930s that his interest in European modernism significantly crystallized. It was from this time that he wrote for the Week-End Review and The Listener to discuss the works of Pablo Picasso, Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst. He was keen to position himself and like-minded British artists as part of the international avant-garde. In 1933, he formed Unit One with practitioners whose work was broadly aligned with surrealism or abstraction. Its launch was announced by Nash in a letter to The Times where he wrote that it was ‘to stand for the expression of the truly contemporary spirit, for that thing which is recognized as peculiarly of to-day in painting, sculpture and architecture.’

He was also one of the main organisers of the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition held in London. This was an event that famously featured Salvador Dalí delivering a lecture from inside a deep-sea diving suit (nearly leading to his suffocation) and Dylan Thomas offering a teapot full of boiled string to attendees. The photographs of the event which are featured in the Nash exhibition, showing a neat but rather cramped display of surrealist paintings in a darkened room suggest nothing of the shock and outrage the event initially caused.

Yet the English surrealist movement had arrived rather late on the scene and to counter embarrassment about its tardiness, its theoreticians attempted to give it an independent force that could set it apart from its French counterpart. Herbert Read, in his Introduction to Surrealism, attempted to forge a distinctive English tradition based on its contribution to literature, tracing the surrealist precursors particularly within Romanticism. While this strengthened the argument reinforcing English Surrealism’s contribution, the corollary that present-day practice found ‘its sources in the native tradition of our art and literature’ and that ‘surrealism is the lineal heir of the nineteenth century’ rather dampened its revolutionary force. The documentary maker, Humphrey Jennings, scorned English surrealists as ‘petty seekers after mystery and poetry on deserted sea-shores and in misty junk-shops’.

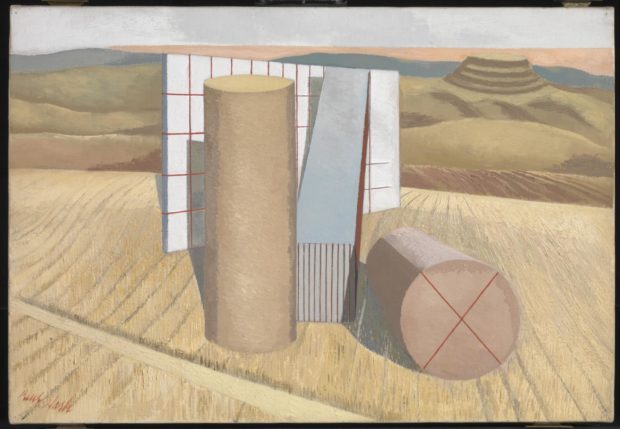

Despite his interest in the possibilities afforded by the formal innovation of modernism, Nash’s choice of subject matter typically shied away from objects with a contemporary reference. The main exception are his images of the Battle of Britain, but even these are zoomorphic depictions of planes – they appear as living creatures, in harmony in the landscape rather then as mechanical objects. This retreat from modernity was expressed notably in his passion for the pre-historic site Avebury and Silbury which became the subject for some of his most striking works, such Equivalents for Megaliths 1935, where geometric forms replace Druidic rock.

While Nash’s output was uneven he was responsible for a body of hauntingly powerful images that emerged from – not in spite of – this fractious relationship with modernity.

The Paul Nash exhibition continues at the Tate Britain until March 5 2017. Tickets are £16.50 (£15 without donation) and £14.50 for concessions (£13.10 without donation).

About Imogen Woodberry

Imogen Woodberry is an AHRC-funded PhD student at the Royal College of Art. She is an assistant editor at Review 31.