You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

A few weeks ago I acquired a graphic novel being published by Jonathan Cape, by a young Belgian artist named Ben Gijsemans. It’s unintentional, but apt, that this novel is set in Brussels, which was so violently attacked a few days ago. It’s also unintentional but apt that I should have read it after reviewing Olivia Laing’s new book, The Lonely City. Hubert functions as a case study for the phenomenon that Laing describes: isolation in an urban environment, a lonely human finding solace in art but unable to connect to another human, even one as lonely as he is.

Writing about graphic novels, assessing them, is something I find tricky, and it’s made harder when they don’t have very many words in them. Hubert was translated into English, but there’s so little dialogue that it could have stayed in Flemish and not very much would have been lost. What people say, in Hubert’s world, doesn’t matter very much; meaning is constructed out of glances, light, the shadows in the crooks of elbows and the backs of knees. He spends his time in art galleries, mostly the Royal Palace of the Arts in Brussels, although we also see him undertaking an excursion to the Musee d’Orsay to see the original of Manet’s Olympia. His neighbour tries to seduce him, but when he finds her arranged artfully (and naked) on her bed, his response is to fetch his mac from the coat hook and leave.

He’s drawn in such a way as to pull my heartstrings in the same way that Wall-E did in the Pixar movie of the same name: hunched back, beaky nose, thinning hair, huge ‘80s specs that make his eyes look simultaneously beetle-like and mammalian, vulnerable and unreachable. His clothes are a plain uniform of beige raincoat, dark red scarf, shirt, indeterminate trousers. It never changes. You want to hug him and tell him that everything’s going to be all right; at the same time, if you saw him on the subway, you’d probably find yourself looking away.

Are we right to feel such pity? Am I right? I used to work in a bookshop in downtown Charlottesville that served a broad cross-section of the city’s residents, from stoned teenagers to yuppie architects to the trustafarian children of old money. A man we saw often was one of the remaining descendants of Thomas Jefferson. He had been an actor; he’d played his illustrious forebear at events all over the state, even the East Coast, for decades. He’d looked a lot like him: red hair, hooked nose, tall, vaguely imperious. By the time I knew him, he’d aged and his mental health was deteriorating along with his body. He came into the shop every Saturday. He wanted to talk to us a lot. Once he tried to give me a candy bar. He lived in an apartment that his relatives paid for. He’s dead now.

He was desperately lonely. His name was Rob.

Hubert’s situation looks similar, but it’s not quite the same. You might think that he is a sad loner—he looks like one—but Gijsemans did an interview with Broken Frontier, an online zine about comics and graphic novels, and he doesn’t talk about his main character as a pitiable figure at all, really. “I never experienced it as a ‘dark’ book,” he comments. “On the contrary, Hubert lives his life the way it works best for him. It’s just that his introverted personality does not allow a lot of room for social contact.” It’s another way of looking at him, certainly. When he escapes the flat of his would-be seductress, we see several panels showing him in an armchair in his own room, staring into the middle distance. In the final panel on that page, he’s taken his glasses off; he has his hand over his eyes. It’s the most self-aware gesture he’s made so far. Is it remorse? Does he feel guilty for turning the woman down? Can he understand her own loneliness and sorrow? Does he feel as though he’s unlike her—that his solitude is a choice where hers is not?

We don’t know; we never know, because this particular graphic novel works more like a film than like a conventional prose fiction story. Free indirect speech is nowhere in evidence. We do not get to find out what Hubert is thinking. We are not entitled to that privilege. The more I think about this, the more I like it. He is fictional, but he’s owed some dignity.

I didn’t know anything about Rob’s life either, but I felt sorry for him, that same combination of wanting to protect and wanting to flee that the uneven line of Hubert’s back evokes. He was asking for someone’s attention, though; he wanted to be loved, or at least cared about, or at least listened to. That was the problem: asking for attention so easily tips into neediness, persistence, pathology.

Hubert is not asking for anyone’s attention. When a hitchhiker from Paris comes back to Brussels with him, he is palpably uncomfortable, either unable or unwilling to have more than the most basic of conversations. The hitchhiker is a young man, and he babbles a little, either out of youthful ebullience or out of a need to fill the silence. Maybe both. Again, like Hubert, we don’t get to find out anything about this man’s inner life; we don’t even get a silent thought bubble.

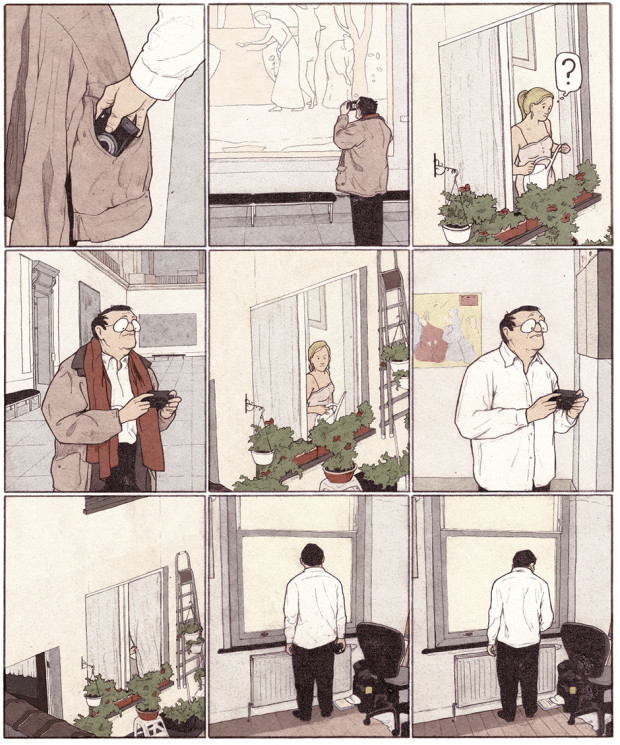

The book’s crisis, such as it is, comes from Hubert taking a photograph of the young woman who lives in the building opposite his window. She sees him taking the snap—it’s nothing lewd, she’s just watering her flowers and wearing a sundress—and her face shuts down into self-protecting anger. I couldn’t say I blamed her. It’s an invasive act, to photograph someone without their permission. It violates something about their space, their very existence. It means that you can have a piece of them they know nothing about, a representation of them that they weren’t permitted to refine or curate or even prepare for. For several weeks afterwards, Hubert does none of his own painting at all. We know he’s turned a corner, as the book ends, because he begins to paint again; he’s painting the woman watering her flowers, the scene in that photograph.

This may not be the point of the graphic novel at all, but there is something deeply fascinating and uncomfortable about the statement being made there with regards to the creation of art. Up until now, Hubert has only painted reproductions of the canvases that he sees in museums; it is only when he connects with someone else—not in a moment of mutual understanding or joy, but in an act that causes shock and surprise and hurt—that he begins to be an artist in his own right. There’s an honesty in Gijseman’s acknowledgment of that. He never valorises the fact that Hubert has caused pain; the girl isn’t presented as irrational or wrong for being upset. But he doesn’t shy away from the fact that, to create art, you need to behave with a certain sort of entitlement: the belief that something you’ve seen or heard or thought deserves to be memorialized. That he’s made this point in a work that is in fact very mindful of its characters’ humanity, very respectful of their inner spaces, makes it doubly impressive.

Hubert is published by Jonathan Cape and available on Amazon for £14.99.

About Eleanor Franzen

Eleanor Franzén is a London-based writer and editorial assistant. She blogs about books at Elle Thinks (https://www.ellethinks.wordpress.com).

In order to find out file explorer windows 10 you may use the methods available in portal we are going to share with you so try out these methods for once definitely these ways will be proved beneficial to you.