You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

The most thrilling and significant international news of this past fortnight has been not the Iowa caucuses or the alarming spread of the Zika virus but the announcement of a new Beatrix Potter book. An unfinished manuscript, The Tale of Kitty In Boots, was acquired by Penguin Books UK, and is set to publish in September of this year, with its missing illustrations supplied by the divine Quentin Blake (whose art adorned my youthful copies of Roald Dahl). It looks exceptional: the one plate of Potter’s which appears to have survived depicts Miss Kitty in hunting boots and khaki jacket, a rifle slung over her shoulder. It’s almost too feminist to be true, even if the blurb does promise some peril in the form of the sinister Mr. Tod.

That being said, peril is, in many ways, what Beatrix Potter is all about. Her books were the first that I read on my own as a child. I adored them with a ferocity matched only by my later love for Little House On the Prairie and Harriet the Spy, but even as a kid—especially as a kid—it was clear to me that there were some dark forces at work in those seemingly idyllic watercolour fells.

Let’s start with the big one: The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which has suffered a contemporary metamorphosis like another Edwardian children’s tale, Thomas the Tank Engine, and now exists in a bastardised version as an animated television programme. (I am aware that this makes me sound like a dour judge in an obscenity trial, but I do not care. There are some things that you ought not to fuck around with, and The Tale of Peter Rabbit is one of them.) It’s passed into national memory as a sort of soothing fable, Peter’s trademark sky-blue jacket instantly recognisable and Mr McGregor a cardboard villain. If you haven’t read the actual book in a while, you could easily airbrush out of recollection the fact that Peter is the child of a single-parent home, due solely to the fact that his father has already met a sticky, pastry-encrusted fate at the hands of the McGregors. (Mrs McGregor, to be precise, who has always struck me as the Lady Macbeth of the piece in any case.) The only reason it seems at all sweet or loveable is because the protagonists are bunnies; translate it into human terms, and suddenly Peter’s apparent lack of impulse control and strange obsession with the garden where his father died looks rather more sinister.

By no means are humans the only murderous creatures in this world. When I first read The Tale of Tom Kitten, I had nightmares, imagining myself in poor little Tom’s position: forced to climb up through the chimney of a house in order to escape the fire lit down below, then abducted by rats and very nearly eaten—again with the eating. There’s a good deal of interest in who’s eating and who’s being eaten, in Potter’s world. She lived on a farm and kept birds, mice, hedgehogs and other small creatures as pets, which she used as models; she’d have known quite enough about the red tooth and claws of nature, as well as about the circle of life. Look at her drawings: frantic Tom showing his needle-like but useless baby teeth, Samuel Whiskers the corpulent rat and Anna-Maria, his thin, ill-tempered wife, the simultaneous claustrophobia and vastness evoked by her pen-and-ink sketches of scenes behind walls or wainscots. They’re almost medically precise, those drawings, but one thing they’re not is sentimental.

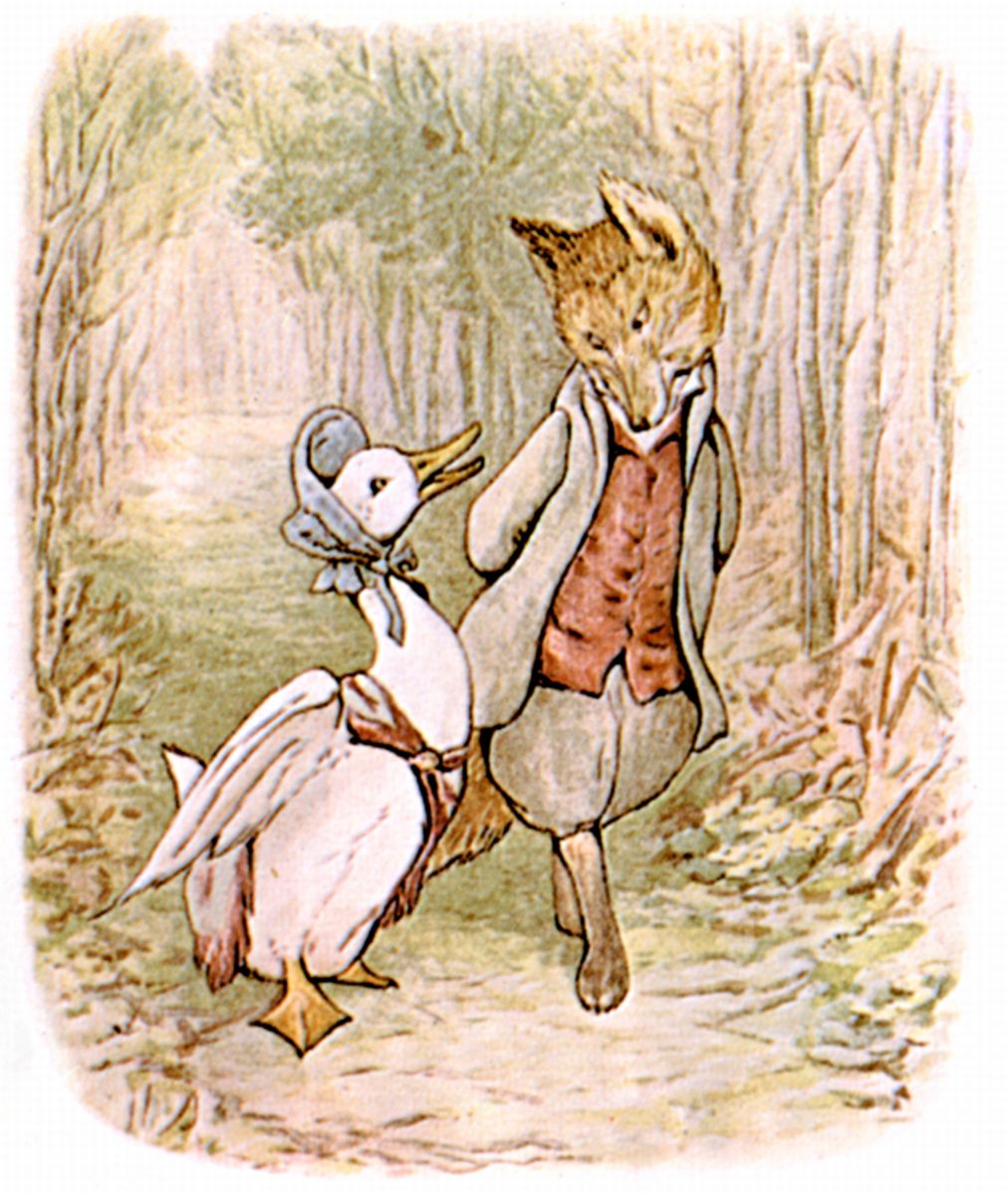

The harder you look, the more you see. Jemima Puddle-Duck is a sweet but thoroughly naive character who only narrowly escapes being murdered by a “sandy-whiskered gentleman”. The reader is well aware that he is a fox, and that he only wants to eat her with sage and onion stuffing, but poor Jemima is just grateful for, and a little bowled over by, the attention. She also needs the help he offers, because she needs to find somewhere to lay her eggs. Translate it into human terms again: a vulnerable woman, on her own, about to become a mother, falls in with a manipulative, cold-blooded man. It’s a scary story. The Royal Ballet Company mounted a production, in 1971, called Tales of Beatrix Potter; you can get it on DVD now, and I watched it a lot when I was a kid. The slow, calculated seduction of Jemima Puddle-Duck onscreen was charged with something that I didn’t understand as a toddler, except to know that it made me feel uncomfortable and frightened. I know what it is now: it’s sexual threat.

Potter married at forty-seven, and by all accounts had a very happy thirty-year marriage. I mention this only because it seems to me that, although reading anything through a biographical lens is dubious, one might try to explain away her dark side by invoking an inability to maintain a romantic relationship. She did have a disastrous engagement with her publisher, Norman Warne, but the disaster was because her parents objected, not to mention because Warne died of leukemia a month after their engagement. She spent much of her young adulthood caring for aging parents (her mother seems to have been especially difficult and demanding); they didn’t discourage her studies, encouraging her interest in all the fields of science, especially botany and mycology. They do seem to have been fairly snobbish and cold, although this doesn’t explain much since it was a default parenting mode for many Edwardians. (Or perhaps, given this fact, it explains a good deal, and not just about Beatrix Potter.)

The reason Potter’s stories have endured, I think, is precisely because they’re strange, with a sense of insecurity that runs under them all. Life is unpredictable, doubly so if you’re small: you could get mauled by an owl, or eat so many acorns that you can’t get out of the door again, or be abandoned by your family. These “little books”, as Potter called them, with their bright, detailed illustrations, speak to the fears that small people have. Children are powerless in a world full of grownups, some of whom might be Mrs. Tiggy-Winkles, but some of whom are bound to be Samuel Whiskerses or Mr. Tods.

Bring on, then, The Tale of Kitty In Boots. Its publication date may be eight months away, but it’s thrilling to think that another Potter story is coming into the world, full of the quietly profound weirdness that made its predecessors so wonderful.

About Eleanor Franzen

Eleanor Franzén is a London-based writer and editorial assistant. She blogs about books at Elle Thinks (https://www.ellethinks.wordpress.com).

2 comments