You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

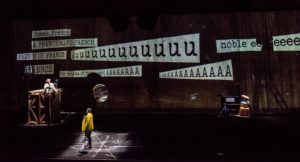

Go shopping“The head and the load are the troubles of the neck.” These words stretch across the length of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. In lamentation, they weigh atop the mass formed by the sheer scale of the space. The words assertively interject themselves into the prejudiced practices of archiving that failed to remember the contributions of African soldiers during the First World War.

Over the next 70 minutes, William Kentridge aims to “recognise and record” the lives of the men, who were often carriers and porters during the conflict. Immediately visible are the apparatus of amplification: horns, platforms, microphones. Something is being interrogated.

For a task such as this – introducing to collective memory years of lost history from over a century ago – the production throws as much as it can to tear down the whitewashed space, in some ways overcompensating to realise a near-impossible goal.

Through his ‘collage’ approach, Kentridge weaves together disparate patches created across the stage – from boxes that unfold to reveal musicians to war meeting rooms re-imagined in the Dada-istic nonsense that might have been. Meanwhilea European avant-garde character enters atop a ladder to argue with the reformed remnants of the past, later donning a helmet decorating with an eagle emblem reminiscent of the German forces at the time.

This is just an excerpt of the content that spills from the edges and floods the stage – barely a quarter of the space is visible at any given time. These patches overlap and collide to create patterns of possibilities. It is difficult to fully take in all the action. Rather, a looming sense of the colossal void of lives deemed insignificant, beyond note, dominates.

During the conflict, England sent instruments to the African soldiers as a form of entertainment – Kentridge’s artwork imagines the sounds and the art they made, which was later erased by the dominant European culture. Instruments are re-interpreted, bodily sounds harmonise and form rhythms before breaking down. Culture itself is reimagined, as the art of the African soldiers enters into an equal dialogue with European movements such as Dada.

Consistently throughout, oppositions make themselves present: shadows and their live counterparts; the capacity for power and frailty in language; human and machine; with the latter dominating throughout.

Blurring the line between body and machine, the performers’ voices are pushed to the boundaries. The piece begins with sung sirens. Soon gramophones are attached to heads and cranked so that the body below may speak. Horn headpieces part to make room for the face to materialise the literal amplification of voices.

These bodies also make the machines on stage run; turning towers and light fittings by hand, though never for their own benefit. As a result, a hierarchy of life forms, in which the human performers’ place is uncertain. A machine-human hybrid.

In a post-modernist dream, Kentridge is presenting the reality of perspective on stage, where the live (body, structure) and the dead (shadow, machine) co-exist together, with the point of origin shifting throughout.

Within the second act, ‘Paradox’, freedom is offered yet constrained within degrees, nullifying the sentiment altogether. Movement of military precision is so constricted that it becomes uncertain whether the performers are moving of their own will. Conversely, the spirit of exploration permeates in a burst of shared traditional dance, before fluctuating to a mid-point.

In the use of shadows and drawings, Kentridge etches history into the walls of the Tate Modern. A production of this size manages to side-step critique of content. In a single viewing, it is impossible to focus on and absorb everything.

Yet the piece’s layered and profound nature is clear. Every element has been thoroughly considered and choreographed by Kentridge and Gregory Maqoma. Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi’s music is urgent, familiar yet alien, always on the brink of something, fighting.

Overwhelmed, I closed my eyes, and allowed the staggering energy of the performers to seep in. Even without the fantastic spectacle before me, everything visible, intended, becomes tangible – reverberated between the bodies assembled in the vastness of Turbine Hall. Kentridge has succeeded in presenting his own version of history.

The Head & the Load played at Tate Modern until 15 July. William Kentridge’s animated film, Ubu Tells the Truth, is playing elsewhere in the gallery on level 2 of the Boiler House.