You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

It’s almost hackneyed to find a fixation with death and sex in the city of Freud. This was a city whose ruling dynasty was thrown into crisis when its crown prince died in a suicide pact with his lover, and a city that spent its money building ornate sarcophaguses and its leisure time touring them in a vast cemetery that artist André Heller called an “aphrodisiac for necrophiles”. Schiele wrote that in Vienna “alles ist lebendig tot,” all is living dead. Sex, regenerative but also pestilential and perilous, was at the crux of a splendid, zombified society. With HIV evolving itself into obsolescence, antibiotics trampling our most gruesome, nose-rotting STIs, the Global North has all but forgotten the latent mortality of sex, its creel of terrible potentials, from pregnancy when maternal mortality rates hovered near 40% to syphilis. Certainly for Egon Schiele, as for his hypocritically erotic and prudish Habsburg milieu, sex was a viper’s nest, prickling with the risks of venereal disease and social stigma. His sister Melanie claimed Schiele’s dalliances with prostitutes were a God-defying game of Russian roulette against the syphilis that disfigured, deranged and killed their father. Schiele’s drawings of carnal pleasure and its squalor made his reputation, but they also landed him in prison, charged with producing pornography and corrupting children.

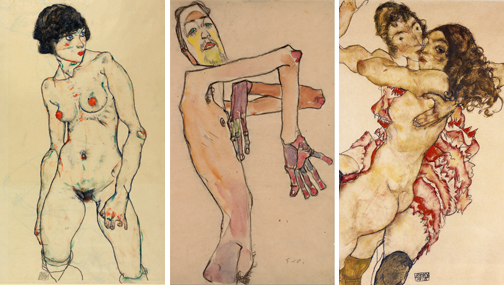

The 38 nudes on exhibit at the Courtauld Gallery are flooded with this sexual danger and Schiele’s libidinal impulse toward self-destruction. Death surfaces in the grotesque, inflamed belly of a woman in a maternity hospital; in the visible ribs of his prostitutes and the green and yellow skin of another; and in his self-portraits, with his spine flayed down to vertebrate, his body contorted and his mouth torn open in anguish. The flesh here is voluptuous but emaciated and discoloured; sex is rapturous but also dehumanising, self-shattering. In Two Girls Embracing, a Sapphic scene is unsettled by the pinprick doll-like eyes of one of the women, an uncanny intrusion of soullessness into a tight embrace.

His female nudes are chopped and splayed: heads are out of frame, arms are pinned back to expose torsos, a pregnant belly dwarfs a body and obscures a face, legs are always split to expose pink labia. Schiele’s enthusiasm for vaginas doesn’t make him a proto-feminist, as The Guardian argued, but he’s not just a male voyeur and he’s not an active misogynist as the surrealists were. His vaginas aren’t teethed, outsized or inflated into grotesqueness; often they’re pink patches of health in wasted body, their promise of fertility and pleasure jostling closely with illness. For example, Sick Girl had a pallid yellow face but a haloed, pink vagina–lost potential of love and futurity in a sunken, small body.

Moreover, Schiele doesn’t reserve this grisly chopping and contorting of the sexualized body for women alone; he extends it most brutally to himself. His depictions of himself masturbating hinge on an unsettling contrast between masculine arrogance and human frailty, between an outsized, pink penis and the ashen angles of his hands and legs. And in Male Lower Torso, Schiele’s legs are so raw-boned, so angular, coldly coloured and cropped that at first only their thatching of hair and the thicket around the genitals are clues to their humanity. He depicts his legs in purple and blue, the colours of bloodlessness, but also of a bruise, so on closer inspection they appear both inhuman and terribly vulnerable—injured or dead. In Nude Self Portrait in Grey, he has severed limbs, shrunken genitalia, electrically shocked hair and a look of Munchian horror. It’s a body petrified, depersonalised in terror.

Leo Bersani, writing in 1987, when HIV was decimating gay communities and reinvigorating a moral panic about the murderous capacity of desire, urged for a construction of sex, and particularly queer and receptive sex, as “self-shattering”, anti-communitarian and anti-identitarian. HIV had simply dramatized for Bersani the ways sex was not a life force promising reproduction and futurity but rather had always been a death drives that breaks, “undoes” the self, releasing it “from the drive for mastery and coherence” and any resolution beyond sexual release. For Schiele destruction and the loss of the self were always intrinsic in sex; he shows that in screams of terror, in empty doll faces, bodies twisted and coloured out of recognition, in the inward-facing, futile attraction he had for his sister. If there’s redemption in these glorious pink vaginas, in masturbation, they’re only transitory. His nudes aren’t radical so much in their eroticism, although that’s what drew the attention of his contemporaries. For us, insulated from the unholy juncture of sex and death, they’re an unsettling insertion of mortality into what’s supposed to be hedonism.

Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude continues at the Courtauld Gallery until January 18.