You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

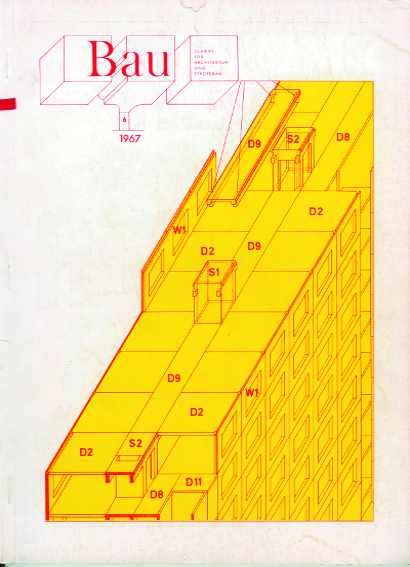

The first issue of the revamped magazine of the Central Association of Austrian Architects—Bau: Schrift für Arkitektur und Städtebau—launched in 1965 with a bang. Or rather, a Whaam!, a stylised blast spliced from Roy Lichtenstein’s 1963 diptych and detonated on the cover. It’s one of a dozen covers from the magazine’s 1965-70 run currently displayed, along with several original issues, in the ICA’s Fox Reading Room, until October.

That explosive first cover was graphic revolt against the prevailing architectural ethos, of Modernism and Internationalism, and a sly discharge of their fascination with machinery and functionalism. That very machinery, new technologies of communication and space exploration, devised, through war, as means of destruction, threatened to invalidate the traditional definitions and contexts of architecture. What was architecture when buildings were only the most basic containers for our lives, when the human sphere was conducted across new dimensions, of media and information, in a Baudrillardian hyperreality of television, theme parks and instantaneous communication? What importance did buildings have when, as Marshall McLuhan wrote, we had “extended our central nervous system… in a global embrace, abolishing time and space”?

To the young editors of Bau, that transition, into the Information Age, into hyperreality, was only destructive in that it was cathartic. The detonation on the first cover of Whaam!, a realistic, outsized recreation of comics’ simulation of reality, is indicative. In the ’60s, Lichtenstein and other Pop Artists were using the techniques and tropes of mass media and consumerism to explode artistic convention and elevate the products of mechanical and digital reproduction as art. The real, with its Benjaminian auras and gross materiality, was dead, increasingly hard to distinguish from an immersive hyperreality of advertisements and television. Hyperreality both spanned the world and brought it closer to us then ever, conjuring distant voices on telephones, figuring faraway places on screens, and even beaming the moon into our television sets. Signs and simulations were the new basis of society, as tangible as the real, if not more so. The editors of Bau reframed architecture for this Information Age, for a time of Marcusian desublimation and space travel. They believed so fully in the potential of mass media that a feature in Bau proposed the replacement of the University of Vienna with a television set.

The most complete articulation of this ideology came from Hans Hollein, in his 1965 envisioning of the Zukunft der Architketur and in the 1968 photomontage manifesto, “Alles ist Architektur,” both published in the pages of Bau. Hollein believed that the Information Age’s extension of the human sphere, its new simulation and mastery of environments—exercised through “TV or artificial climate, transportation or clothing, telecommunication or shelter”—allowed for the concurrent expansion of architecture. He envisioned architecture as environmental determinism and scaffolding for these “new media of determination,” as a “conditioning of a psychological state” and a medium of communication. A building’s meaning lay only in how it affected people, how a person used it, took possession of it/appropriated it (“von [etwas] Besitz ergreifen”). If there was no difference between material reality – between a building and its simulation through media, its photograph in newspapers and broadcast on television – and if, in fact, that simulation was often more salient – if more people saw images of the Acropolis and the Pyramids at Giza through media than saw then in physical reality – then a building “could become entirely information,” extending far beyond its physical footprint.

Buildings were not only passively funnelled into this network of information—photographed, filmed and replicated. They were also key nodes in its infrastructure, plugging man into a boundless world of information. For example, Hollein argues, a telephone booth had global reach that belied its small size. Bau recalibrated the scale of architecture, both expanding and contracting what the field considered and attempted to design and manage. Liberated from three-dimensional space, from the simple mandate of shelter, architecture could address all sensory experiences and bodily needs of man. Hollein called for an architecture that annexed and found symbolism in the infrastructure of communication and Versorgung—a word whose definitions span an economic “supply” and “provision” but also more intimate “sustenance” and “nourishment”. He claimed as architecture helmet of a jet pilot, which “through telecommunication, expand senses and bring vast areas in direct relation” to the pilot, and even space suits and space capsules, “houses” that could sustain man entirely, providing for all his bodily functions. In Hollein’s construction architecture addressed “the haptic, the optic, the acoustic” and produced everything from clothing to inflatable structures to space stations.

There’s something frustrating and contradictory about the staging of the archives of a magazine in a gallery space. At the ICA, those wishing to read the text of Bau issues must squint through glass at stretches of German sucked into the fold, or leaf through photocopied reproductions chained to the wall. The focus of the exhibition is perhaps inevitably on the visual, with outsized reproductions of covers on the walls and issues split open to their most visually provocative, packed pages. It’s an appropriate choice, given the weight Bau places on the visual. Hollein’s manifesto, and the magazine in general, laid down their prophecy for architecture in a journal styled as a fashion magazine, with full-bleed printing and slick advertising. The medium is the message – and the message here was of the realness of simulation, the value of pop culture, and architecture’s link with mass media and the media of reproduction. Today, Bau would likely have dispensed with print all together and launched a website, or perhaps, given their elevation of images over text, a Tumblr, a platform whose blog themes and game-of-telephone style reblogging easily shear all (con)text from images. “Alles is Architketur” is a thousand-word manifesto framed by nearly 90 images that illustrating that “alles” and assert a new scale and materiality for architecture. The images enact Hollein’s subversion of architecture’s size and material limitations with vertiginous scaling: huge images of a tube of lipstick overwhelm entire pages and in a print of Magritte’s “Les valeurs personnelles” a giant comb balances on a bed while a huge makeup brush lurks on top of a wardrobe. Meanwhile, Che Guevara is reduced to a postage stamp on a white field, the same magnitude as a pill, printed in life-size, on another blank page.

This warping of scale and Hollein’s centring of the body in architecture, his vision of its extension and the creation of “Man-made space”, are inscribed in repeated images of outsized bodies, always women, often nude, and the landscapes they dominate. A giant woman strokes a car in a tire advertisement, one of Tom Wesselmann’s “Great American Nudes” (number 81) is given a speech bubble to assert that “Alles ist Architektur”. The use of female bodies to manifest this extension of the human senses and sphere is a sexualisation, parallel to—directly lifted from—the sexualisation of women in mass media and in the high art apparently opposed to it. But the photomontage also uses the female nude as a node and vessel for its wildly diverse collection of images, of disparate objects and structures claimed as architecture. It pastes in photographs of Niki de Saint Phalle’s “She: A Cathedral,” a colossal pop sculpture of a supine woman, with her vulva placed as entrance to Stockholm’s Moderna Museet. Section diagrams of this body show the dizzying “multi-use” space behind the vulva, with a cinema, bar, gallery, aquarium, planetarium, children’s slide, “lover’s nest,” viewing platform and working telephones, hooked up in the navel. Her own inscription captures the space’s—and the female body’s—multiplicity of uses and meanings: “HON:SHE A Cathedral → Factory Whale Noah’s Ark Mama.” The female body, specifically the womb, was the original life-supporting vessel, the incarnate space capsule Hollein envisioned as the zenith of this new architecture. It’s a capsule for sustaining life but also for collecting and resolving disparate meanings and uses. It provides the logic that decodes and coheres this diverse vision of architecture, the manifesto’s photomontage of everything—pills and soap bubbles and sunglasses.

Bau began with an explosion, a spiral toward entropy, expanding the reach of architecture, what it considered, the space it could span. But the blast on the first cover was also, paradoxically, an implosion, a contraction. It’s surrounded by a tight, gridded collage of photographs, circling around the blast but otherwise static, their only motion from their strange vertiginous scaling. A photograph of the colossal Verrazano-Narrows Bridge is framed to look like a toy town and slotted beside a tightly cropped photograph of an architectural model. Aerial photos of the pyramids at Giza and a rocket launch site sit next to magnified structural sketches. “Whaam!” is an implosion, of the Baudrillardian type, collapsing simulation and reality into each other, reversing their sizes, but it’s also a contraction of the bounds of architecture, tightening them around the body and its needs. “Alles ist Architektur” presents a dizzying, expansive collection of objects, structures, and bodies, and then resolves their incongruence and eclecticism by claiming them all as a single entity–architecture—an amalgamation incubated and cohered in the female body. In this brave new world of information and simulation we’re reaching for the stars, but we’re tumbling back into the womb, where it all started, with spacesuits and capsules that approximate it. Ashes to ashes, dust to space dust.

Everything is Architecture: Bau Magazine from the ’60s and ’70s continues at the ICA until October 4. Entry is via day membership, set at £1 during exhibition hours.