You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

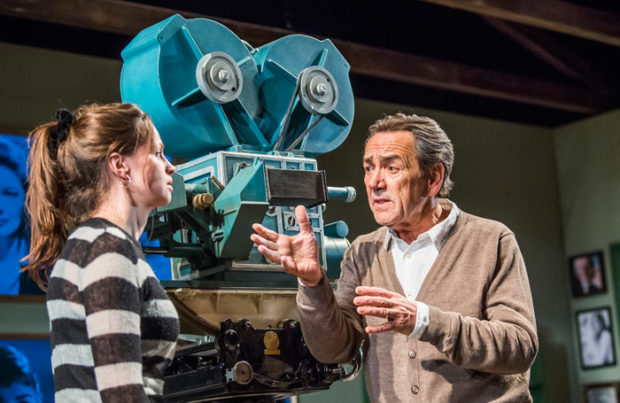

What happens when a man who devoted his life to his craft, who reached the pinnacle of his profession, who achieved greatness, fame and wealth finds himself retired and succumbing to dementia? In this play, he finds himself in his garage, transformed into a special “man cave” complete with his trophies, memorabilia, even his (lobotomized) Technicolor camera. He is surrounded no longer by movie stars and famous directors, but instead by his middle-aged wife Nicola (Claire Skinner) and grown son Mason (Barnaby Kay). The latter has just hired a carer Lucy (Rebecca Night) that he’s tipping extra to type up his dad’s biography. It’s a promising set-up. Terry Johnson has written and directed a lovely tale of decline and twilight without an ounce of doom. Robert Lindsay is awesome as the legendary British cinematographer Jack Cardiff, the man who “redefined” cinematography for much of the twentieth century. Known as the master of light, the “man who made women beautiful”, he holds a prism in the play the way a blind Phorcides sister holds an eye.

We don’t see Cardiff in his glory days. We don’t need to. Jack carries his past like a cloak that he wraps himself in. We hear Jack and Mason before we see them. They are standing behind the garage door, waiting for it to be raised. The dialogue is lopsided between the low-flying Mason and Robert Lindsay’s fabulous Jack Cardiff: charming, confused and a pitch-perfect Hollywood aristocrat. Mason is hoping his father can write his memoirs before he loses his mind completely. That’s why he’s fitted the garage out for him. But Jack perceives the gradual opening of the garage as either an exercise in stage lighting or the entrance to the pub. Nicola walks in but after hearing Jack’s welcome, we are not sure who she is. Claire Skinner does a subtle job at playing the ex-personal assistant: no longer young but still blonde, and still coming to terms with what it means to marry your brilliant, iconic, 27-year-older boss. In his 2003 play Hitchcock Blonde, Johnson wrote about the relationship between a young unknown blonde and the middle-aged, bloated and iconic Alfred Hitchcock. Almost fifteen years later, here he is catching up with a similar couple. In a poignant moment, Nicola winces ever so lightly when Jack calls her for the nth time “Kate”. Hers was the first name he forgot, Nicola explains.

Tim Shortall’s set matches the tone of this play perfectly: warm, bright and nostalgic. There are pictures, taken by Jack himself, of Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn and “Kate” Hepburn too. There are also imitations of paintings by Vermeer, Van Gogh and Rembrandt to “frame” the garage: these are Jack’s original studies in light. The new carer Lucy is unimpressed by all of this. Rebecca Night is compelling in the skin of the millennial young woman who doesn’t like “old films”, can only type with her thumbs and is the first person to tell Nicola and Mason that it’s OK for the old man to indulge in his fantasies. Jack doesn’t want to write his memories: he wants to reside in them.

From here we are transported to the Congo in 1951, to the set of John Huston’s The African Queen. Rebecca Night becomes Katharine Hepburn – and here I had to suspend my disbelief because I have The Philadelphia Story engraved in my head and I can tell Katharine Hepburn’s voice a mile away. “Kate” is hot and bothered, her head covered by a ridiculous hat that also serves as a mosquito net. There is an ominous scare but I’ll stop there. Barnaby Kay is a great Humphrey Bogart and Jack Cardiff is there to capture them with the Technicolor camera in full action, complete with prism. They flirt; “Kate” calls Jack’s crush on her out. She only has eyes for her Spencer. She was the star who got away.

The loveliness of Prism is that although it makes clear that Jack was rewarded for making stars “beautiful”, that his work took the best of him and that Nicola and Mason had to make do with the crumbs, they forgive him for it. Jack always had a higher purpose. It was never about him in the end, but about the light. Every time Jack talks about lenses, filming and colours, even in the grip of dementia, it is with such visceral knowledge and respect, such grace, that we forgive him too. Just like his wife and son, we know what the world has lost when we see Jack in the dark. A prism gone forever.

Prism continues at the Hampstead Theatre until Oct 14. Tickets are £10-£37.

About Isabelle Dupuy

Isabelle Dupuy is a writer based in London. She is currently working on a novel "Living the Dream"

Awesome. Such a vivid description!!

I love reading through an article that can make people

think. Also, thank you forr allowing me to comment!

awsome